A Skiing Reverie

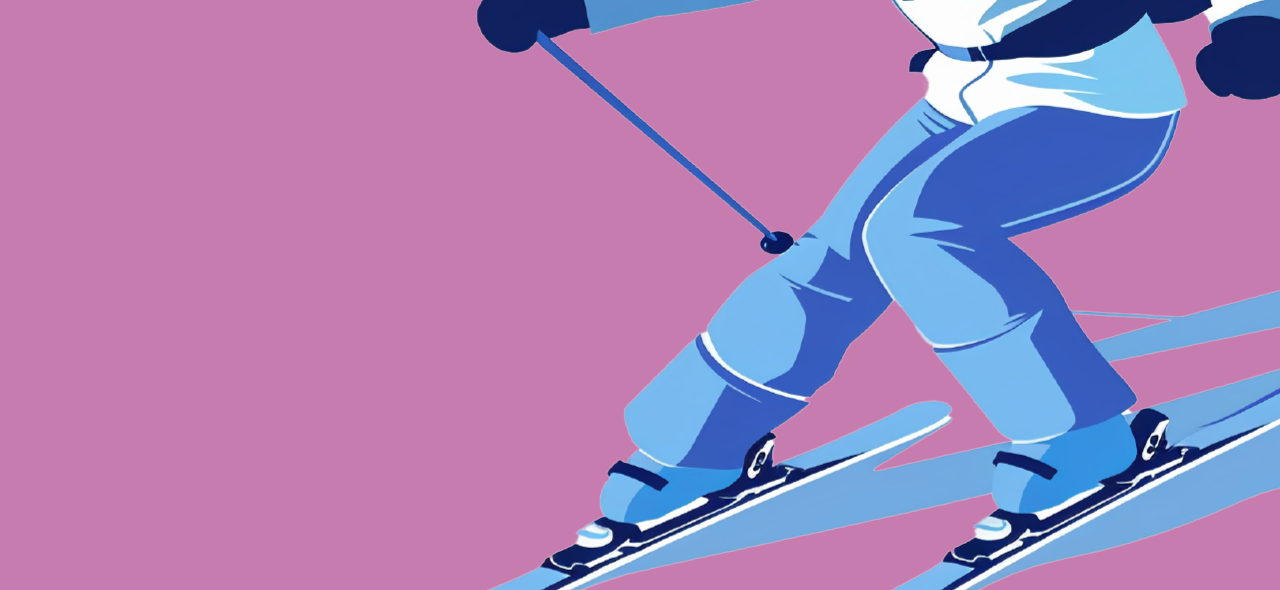

When life events overwhelm me — family health issues, major expenses, needless arguments — I dream about skiing. For me, there is no better escape than soaring down a slope with nothing on my mind other than my next rhythmic turn. Skiing is great therapy, even in a dream.

But I’ll probably never ski again. I have two fake knees and a stent. My cousin sold the Steamboat Springs, Colorado, condo we enjoyed for years, and this past fall, my husband parked my outdated skis, boots and poles on the curb for the trash.

Still, I’ll miss skiing forever.

There were no PIAA sports for girls when I was a teen — just gym, where taking showers was the main activity, and after-school intramurals. Lacking the opportunity for team sports, I enjoyed swimming, tennis and horseback riding. But skiing is the only sport I ever truly loved and mastered — and it took half a lifetime.

I was a sophomore when I first laced up leather boots and inserted them into the tricky cable bindings on a very long, skinny pair of rental skis. The occasion was a date with my steady boyfriend at Laurel Mountain Ski Area, a worthy competitor to Seven Springs before that resort’s expansion. I wore brown wool slacks and a peacoat — I didn’t own waterproof ski clothes. Like all first-time skiers, I spent more time on the ground than upright, and by the day’s end was covered from head to toe with huge clumps of frozen snow. My only triumph was learning to ride the T-bar and poma lifts — there were no high-speed quad chairs back then.

My awkward debut did not scare away my boyfriend, who was skilled on the slopes, but my love affair with skiing lasted decades longer than he did. The following Christmas, I begged for skis. My parents wouldn’t spring for the fancy black metal Head or Hart brands, but my dad did help me choose a nice pair of wooden Northland skis at Kaufmann’s department store (Willi Klein of Willi’s fame probably was still back in Austria). Once home, Dad wrote “Sue ‘F’” in red nail polish on the tips of the blue skis so no one would steal them. How embarrassing!

That winter, several of my friends who could ski well and had cars began inviting me to the Laurel Highlands to ski every weekend. At rustic Laurel Mountain, Broadway and Upper Wildcat were the first slopes I tentatively mastered. The still-iconic Lower Wildcat, a short run with a nearly 60 percent slope, beckoned but eluded me. We also skied Seven Springs, where Alpine quickly became my favorite.

I don’t even know if there were ski instructors back then — my parents wouldn’t have paid for one anyway. So, I decided to follow the best skier in our gang, mimicking every move. Somehow, it worked, and my pigeon-toed snowplows turned into stem/christies and eventually into graceful knee-knocked parallel turns that were the standard before the shorter, oddly shaped parabolic skis mandated a wider stance.

By the time I went to college in flat-as-a-pancake Ohio, I was skilled enough to teach my roommate, Ann, to navigate the tiny ski slope at Bellefontaine, where the long scarf I forgot to tell her not to wear got caught in the rope tow mechanism and nearly strangled her. Fortunately, she survived and ironically ended up in Park City, Utah, where she became one of the fastest, most fearless amateur skiers I’ve ever known.

Fast forward a few years, and my husband and I drove to Mt. Snow, Vermont, for a week, where we enrolled our 6-year-old daughter in ski school and nearly froze to death on the slow, first-generation chair lifts, even though we wore Teflon face masks.

The next year, we headed for Vail, Colorado — my favorite place on earth — where the sun usually shines, and, unlike on the East Coast, the slopes are never pied with patches of rocks and mud.

That first year at Vail, I made a late afternoon run (bad light, dangerous time of day) down the daunting Look Ma, caught an edge, did a cartwheel in the air, heard a loud snap and ended up with my leg shattered and wedged against a mogul. “Will I be able to ski again?” I sobbed when I arrived at the hospital after a long sled ride down the mountain with the ski patrol and a short ambulance ride. The next day, I flew home in a temporary cast and had surgery at Mercy Hospital, followed by four months on crutches and a second surgery to remove the hardware that had screwed and pinned me back together. Undeterred, I sat out one season and returned to Colorado, happy to be back but more cautious. I skied for 35 more years.

Two seasons ago, in the morning before the sun had softened the snow, I fell on a steep crunchy slope at Steamboat. I wasn’t hurt, but I couldn’t pull myself up with my poles. I took off my skis, stood up and tried to step into my bindings, but because of the steep angle, I couldn’t stomp hard enough to clamp my boots into place. A young family of four skied down and asked if I needed help. “Well,” I told the father, “if I can hold onto your shoulder, I think I can snap into my bindings.” He obliged, and then politely asked if I’d like to ski down with them. “Oh no, I’ll be fine, thanks,” I said, looking toward the base, where my ski buddy was waiting. As my rescuers skied away, the mother called out, “Don’t feel bad. That used to happen to me all the time when I first was learning to ski.”

I didn’t admit I’d been skiing for more than half a century. But I haven’t forgotten her comment. Maybe it is time for me to sip a Corona on one of the outdoor decks and watch my grandchildren, who get fancy new equipment every year and do Olympic-style flips and jumps, and schuss down the mountain.

On the other hand, next time I’m stressed, I’m pretty sure I’m going to ski down my forever favorite, Vail’s famous four-mile-long Riva Ridge, a medley of cruising blues and challenging black diamonds with beautiful views — if only in my dreams.