Part tragedy and part myth, as well as part history and part prophecy, Pittsburgh Opera’s “We Shall Not Be Moved” (which premiered in 2017) may be one of the most modern theatrical spectacles you will see — with its synthesis of music, singing, dance, and video projection — yet it may also be one of the closest embodiments of classical Greek drama that you may witness as well, in the way it explores the human condition in such a visceral, ancient manner.

Using the 1985 bombing of the black liberation MOVE organization in Philadelphia as a starting point — in which 11 members, including 5 children, were killed by police, who dropped incendiary devices on their home — the narrative follows a group of teens who decide to inhabit the same location and form a family three decades later.

What director and choreographer Bill T. Jones offers is an archeological story, built on layers, much like a Greek tragedy — with its generational inheritance of suffering — and using the same tools of song, dance, actors and a chorus. It should be remembered that the ancient Greeks believed in the curative powers of sung poetry — their dramas were in verse and not spoken — and often built temples dedicated to the god of healing, Asclepius, next to their theaters, which acted as a kind of medicinal stereo system for the audience.

The five teens occupy the remnants of the former MOVE location and find themselves communicating with the ghosts of the place, or the OGs, as they are called. These mysterious apparitions are dressed in white hoodies and offer advice, like a Greek chorus, urging the teens to follow their ideals, and perhaps, their destiny.

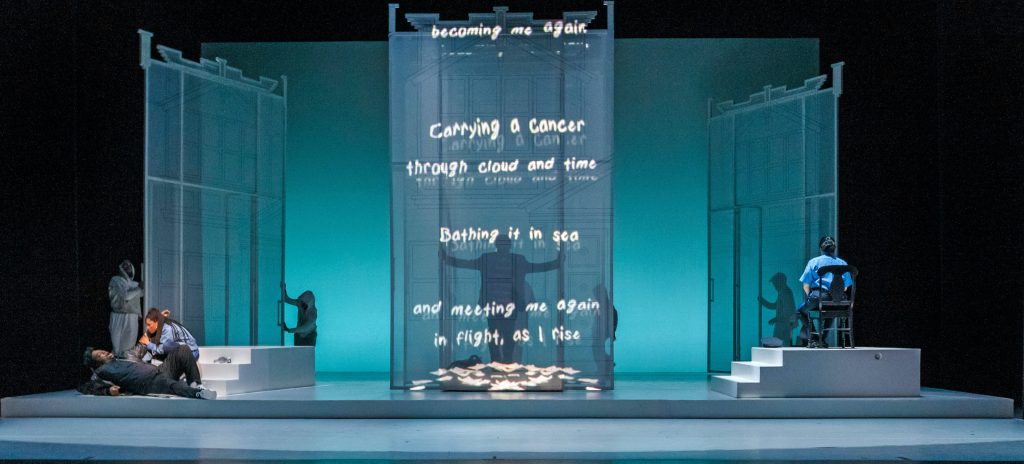

The musical numbers are interspersed with spoken words, voiceovers, and video text projections, some of which constitute dialogue, and some of which are history lessons. The most impactful moments combine dance — which might be live or projected on the scrims layered across the stage — partnering real figures with projected ones, as if the beats are flowing through bodies and catching themselves on the translucent screens, like cartoon souls shot out of their flesh. It’s a mesmerizing effect, and the opening numbers brought me back to those rock musicals of the 1970s in which you’d see a bassist playing electric funk sitting next to a classical violinist evoking rhapsodic washes of melody.

Daniel Bernard Roumain’s score makes the nine-piece Pittsburgh Opera Orchestra, conducted by Viswa Subbaraman, sound like a full symphony, and meshes harmoniously with Marc Bamuthi Joseph’s libretto, which manifests a lyrical resonance of its own, in lines such as “An agony so deep the sky bends,” or, “What good is it to have the youngest bones in the graveyard, Lord?”

What seems to be a workable living solution to the teens is interrupted by the appearance of a police officer, Glenda, who has a gun in her holster and, as we know from Chekhov, if that gun appears on stage it has got to go off, and it does, which changes everything. Thus, the old tragedy of MOVE is rekindled by this police presence, and a new tragedy develops, which puts the teens in a perplexing reversal: what to do now when they hold the life and death power over authority that the police once held over their ancestors?

Heading up the excellent company are Alexa Patrick in the role of Un/Sung, the leader and conscience of the teens, and Kirstin Chávez, as the cop. Both are able to move between spoken and sung dialogue with ease. Also outstanding are the other principal members of the cast: John Holiday, Chance Jonas-O’Toole, Adam Richardson, and Ron Dukes.

Special accolades should be given to the technical personnel of the production team: Matt Saunders’ scenic designs are a character in themselves and lead us into psychical dimensions not navigable through words or actions alone. Complimenting this effort are Jorge Cousineau’s video projections, Robert Wierzel’s lighting, and Robert Kaplowitz’s sound designs.

Much to the credit of the librettist and director, we are not told how this story ends. Like the strongest tragedies, we are presented with moral ambivalence, not pronouncement.

I used the word “prophecy” at the beginning of this review as one of the essential characteristics “We Shall Not Be Moved” offers us, not in the sense of a foretelling — which is a modern adaptation of this word — but in its ancient meaning of the passionate need to tell the truth. As Abraham Heschel has pointed out in his seminal work, The Prophets, “The prophet is a man who feels fiercely . . . his images must not shine, they must burn . . . the prophet is an iconoclast . . . he employs notes one octave too high for our ears . . . [he] was an individual who said NO to his society, condemning its habits and assumptions, its complacency, waywardness, and syncretism.”

This perspective goes back to the Biblical texts of the eighth century BCE, making the arc of this show’s revelation closer to 3,000 years, rather than a mere 30. Yes, this is a dazzling operatic spectacle utilizing many of the digital wonders of technology, but what really counts here is the interior journey we are taken on, and the questions we are implored to answer about where we live, inside ourselves.

WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED runs through May 21st. August Wilson African American Cultural Center, Downtown. Tickets $15 – 121.50. www.pittsburghopera.org, or 412-281-0912.