The Course Loved ‘Round the World

The U.S. Golf Association began staging the U.S. Open — the ultimate national championship — in 1895, and moves it year to year around the country. The USGA requires, first of all, a golf course that offers a stiff challenge, where the rough is deep, the greens fast and par is an outstanding score. It’s a compliment to a course to be selected for the Open.

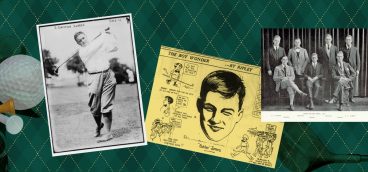

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”19″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Oakmont Country Club has hosted the U.S. Open in 1927, 1935, 1953, 1962, 1973, 1983 and 1994. The 2007 Open in June is a record eighth. It is also Oakmont’s 20th national championship, another record. Oakmont has hosted five U.S. Amateurs, one U.S. Women’s Open, three National Intercollegiate Championships (now known as the NCAA Championship), and three PGA Championships. The PGA, the U.S. Open, the British Open and the Masters are golf’s four major championships. The U.S. Open is the toughest of all to win.

Golf is not totally satanic, as some sufferers of the game would have you believe. There are aspects that are Biblical, if not downright religious, as W.C. Fownes Jr., the crown prince of Oakmont Country Club, revealed in some of his pronouncements. He would go around Oakmont thundering, “A shot poorly played should be a shot irrevocably lost!” And if that’s not a whiff of Dante’s sulphur, what is it? He also roared: “Let the clumsy, the spineless, the alibi artist stand aside!” Could there be an echo of Calvin in there?

In a gentler day, when it was a sin to use the word “hell” except from the pulpit, Oakmont was known as the Hades of Hulton, after the road that runs out front. There was a time when Oakmont was considered the hardest course in the world. There is no way to prove such a contention, but it’s safe to say that Oakmont was and is among the toughest. All of this by way of explaining that Oakmont has been afflicting golfers for 103 years and probably will be no less disagreeable when the best golfers in the world — Tiger Woods, of course, Phil Mickelson, Jim Furyk, Vijay Singh, et al. — descend to play the U.S. Open, the toughest tournament in the world.

It all started with a man named Henry C. Fownes, who could control his steel businesses, and by God, he would control this game of golf or know the reason why not. He also once thought he was going to die young. And from all this emerged one of the great golf courses of the world.

Fownes was founder, designer, builder, president and ruler from the founding of the club in 1903 to his death in 1935. W.C. Fownes Jr. was his son, named after an uncle, and was second in command from the beginning, and then, upon the death of his dad in 1935, overall authority until he resigned in bitter disappointment in 1948. Oakmont’s reputation as a monster came principally from two features — its fiendishly fast greens and its bunkers.

W.C. was loathe to let a poor shot go unpunished, and so a stray ball would soon be followed by another bunker. Oakmont is said to have once had some 350 bunkers. (There are 210 for the 2007 Open.) Up until the 1960s, the bunkers were filled with heavy sand from the Allegheny River and raked with the devil’s backscratcher, a long, heavy rake with huge teeth that gouged deep furrows into the sand. It was all a golfer could do to get the ball out. Hitting the green from a fairway bunker was out of the question.

The greens were often said to be the fastest in the world. This reputation was helped by Sam Snead’s line, “I put a dime down to mark my ball and the dime slid away.” The “speed” of the green — meaning how far the ball will roll from a standing start — is given in feet. Tournament speed on the PGA Tour is usually near 10 feet. Oakmont’s speeds usually begin at 11 and often run higher.

Talking about how to prepare the course for the U.S. Open — meaning rough, green speed, bunkers, etc., Lee Trevino once said, “There’s only one course in the country where you could step out right now — right now — and play the U.S. Open, and that’s Oakmont.”

Then he stopped himself. “First, you’d have to slow down those greens,” he said. “You can’t play the Open on those greens, the way the members play them. Man, those members are crazy.”

Great golf clubs can trace their roots to romantic notions or grand ambitions. Bobby Jones, for example, wanted a kind of Shangri-la for himself and friends, and Augusta National was born. Dr. Laidlaw Purves wanted to have a Scottish-style course in England, and there sat Royal St. Georges.

All Henry C. Fownes wanted to do was patch a bicycle tire.

H.C. was the son of English iron people who came to Pittsburgh in the early 1840s, married and got into the iron business. H.C. was born in 1856 and had to quit school when he was 15, when his dad died, to help in the family business. Before long, he was an iron and steel magnate and running things as he would all his life.

Fownes Bros., a holding company formed by H.C., acquired, developed and sold businesses. Among their businesses were the Carrie Furnace Co., a blast furnace in Rankin; Standard Seamless Tube, Midland Steel, Reliance Coke and Shamrock Oil and Gas, in Texas.

The pivotal day in H.C.’s life occurred in 1898. He was trying to patch a bicycle tire. This required heating a piece of wire. He used a welding torch but neglected to put on the welder’s mask.

Doctors were soon telling him that the dark spots in his vision were due to arteriosclerosis. This was unbelievable. The outlook was even worse. They gave him two or three years to live. He was only 39.

“This information was very depressing,” wrote his son, W.C., “and as a result of it he gave up business and traveled about the country seeking relaxation.”

It was somewhere in this period that H.C. came upon golf. Also somewhere in this period, another doctor lifted the death sentence: The dark spots weren’t from hardening of the arteries; they were macular damage from the intense light of the torch.

H.C. had become badly hooked on golf. He was playing out of the original Highland Country Club, but he improved so rapidly that soon he was looking for bigger challenges. But there weren’t any. He’d have to build his own, and for a man who had never designed or built a course, that was fine with him.

Golf had touched down at various places in the United States, but the first golf club to take root and stay was Foxburg Golf Club (now Foxburg Country Club) near Clarion, founded in 1887. The credit generally goes to St. Andrews, in Yonkers, N.Y., which didn’t come along until a year later. As to why Foxburg never really received its historical due, the best guess is location: St. Andrews was on the edge of New York City, and Foxburg was on the edge of nowhere. At all events, golf spread rapidly and first as a game for the rich.

John Moorhead Jr., a Pittsburgh steelman, was introduced to golf in 1893 in Massachusetts and was so smitten that he came home babbling to himself and everyone else. Feverishly, he sank six pea cans at the old Homewood racetrack at Homewood Avenue and Frankstown Road — Pittsburgh’s first golf course. And in 1895, he founded Allegheny Country Club, then on Brighton Road (now California Avenue) on the North Side. The game spread quickly.

H.C. took up golf in 1898, at 41, relatively late in life. But consuming the game and being consumed by it, he quickly became one of the best in the area. By 1901, at age 44, he qualified for his first U.S. Amateur, as did his son, W.C., then 24.

Where Moorhead and others like him wanted something more formal than tin cans sunk in the ground, H.C. wanted a course with muscle and bite. But first he needed the land.

Deliverance arrived one day when George Macrum, a banker and Oakmont resident, told him that White Oak Level was available. It was close to the city. It was comparatively flat, which meant easier walking. Best of all, it was open farmland, which meant there were few trees to drop and few stumps to pull.

Fownes had already formed an investor group, and now he called it the Oakmont Land Co., with himself as principal investor, and Oakmont Country Club was born in a fierce rush.

The Oakmont Land Co. was chartered in May, 1903; by July, they had bought 191 acres. The club — to be named later — was incorporated on Aug. 17. On. Sept. 15, H.C. sent out a crew of some 150 men with 25 teams of horses, or maybe mules, and the first 12 holes were done before winter set in. The others were completed after the weather broke in spring of 1904, and they were teeing it up by summer, in just under a year.

With H.C. driving the project, the action was so fast, in fact, that the clubhouse, by noted Pittsburgh architect Edward Stotz, was ready for the grand opening on Oct. 4, 1904. Stotz termed the style “English Domestic.” The back stairs still creak.

But it will be a new Oakmont the world will see in the 2007 U.S. Open. Or rather, the original Oakmont.

Oakmont, as a former farm, had been a nearly treeless course since its beginning. But in a beautification program in the 1960s, the course began filling up with trees.

Finally, said some critics, they couldn’t see their Oakmont for the trees. It was just another country club. It didn’t look like Oakmont, didn’t play like Oakmont. The trees were sucking up water and nutrition from the ground, and as they grew, they began affecting play more and more.

Early in the 1990s, the dissidents began cutting down the trees, sending out work crews in the pre-dawn dark, a few here a few there, in hopes the piecemeal work wouldn’t be noticed. But of course, they eventually were found out.

The issue split the club. But the pro-cutting faction had its way, and eventually, some 5,000 trees were felled. Now Oakmont is open, looking as it did in the aerial photo from the 1920s, hanging in the clubhouse.

And now people on the back veranda behind No. 9 can see all the way to No. 2 in the distant corner, and to No. 3 far to the left. It’s a view not seen since the time of the 1953 U.S. Open.

Other prominent courses have been laid out by amateurs, but Oakmont was a totally solo flight by H.C. He tramped his new property, sketched out his course and with one exception, the holes sit where he put them. No. 8 green, the lone exception, had to be moved perhaps 10 yards to make way for the Pennsylvania Turnpike being constructed in the 1940s in the cut that divides the course pretty much between the front and back nine holes.

It seems an article of faith in golf history that although H.C. laid out the course and oversaw the construction from the first day, it was his son W.C. Jr. who turned it into a monster by adding treacherous bunkers.

In his brief, typewritten autobiography — the only written account of the Fowneses — written in the clinical style of an engineer, which he was, W.C. makes it clear that he idolized his dad. He also makes it clear that his dad was boss in all matters. At least one member discovered that as well. He came from the shower to his locker to discover his clothes and golf clubs waiting for him. The attendant informed him that he had violated a club rule and had been expelled by H.C.

And so H.C., who scrupulously kept controlling interest in all things, is not likely to have surrendered his precious course to anyone. Thus changes to Oakmont were either ordered by H.C. or approved by him. And after H.C. died in 1935, it had to be dogma that W.C., whom he’d named to succeed him, would keep faith with his father.

W.C. would exit on a sad song. His dad founded Oakmont as a golf club, and he insisted on keeping it that way, like a British golf club — few social activities, no frills. But the American country club was family oriented. There needed to be activities for the entire family, especially a swimming pool for the kids.

The pressure on W.C. increased as Oakmont’s membership weakened. He refused to bend. At the same time, he knew Oakmont’s life depended on change to attract more members. So he removed himself as an obstacle.

In 1946, in a final great gesture of contempt, he resigned, not just for himself but for his son, H.C. II, as well, who was next in line in the Fownes Dynasty. The board of governors persuaded W.C. to let them continue using his name, to keep up appearances and keep the Fownes name at Oakmont. W.C. did it for two years. Then wearying of the fiction, he quit totally in 1948. For the first time since 1903, the Fownes name was gone from Oakmont. But their monument lives on.