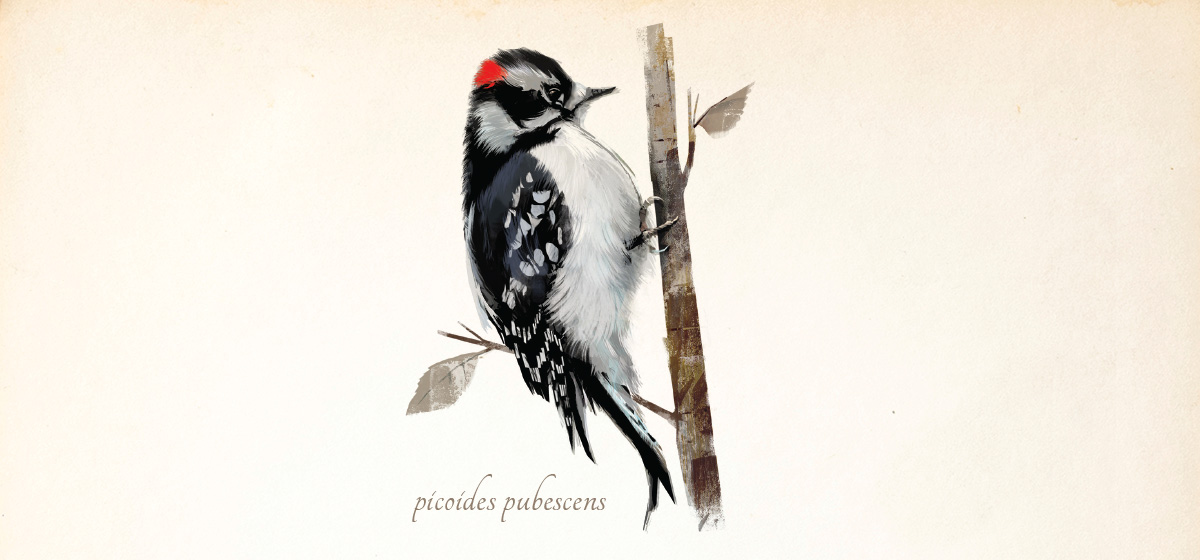

Set aside that steaming cup of cocoa and watch. Your bird feeders, flecked with last night’s early snow, beckon. That black and white blur is the first downy woodpecker of the day. There is a red streak on the head: the male. He’s a regular. The chickadees and titmice are his winter companions. They flock up, the bigger the crew, the better to watch for predators and seek culinary alternatives when you forget to refill the bird seed and suet. For once during this long pandemic year, it’s okay to be quietly inside. Nature, insistently following its accustomed rhythms and patterns, has been a balm. The yard birds especially so.

Downy woodpeckers visit our yards all year and stake out regular territories, so the guy with the red stripe is probably the same bird you’ve seen all year. Later this winter, he’ll drum with his short, chisel-shaped bill on your trees and maybe the side of your garage to attract a female, but for now, he’s just using his keratin snout to dig out fatty morsels from your suet feeder. Good thing you refilled it. It’s getting cold, and the extra fat helps the downy and his buddies get through the night more easily. That, and using his feathers for insulation. They’re an amazing adaptation, allowing the bird to puff up, then trap and heat layers of air between his feathers and beat the chill. With a body temperature that typically runs around 105 degrees, he’s like a feathered furnace, as long as he keeps the fuel tank full. That handy bill lets him drill and find food no matter the weather.

That tapping! The woods and yards will be full of it in spring, but for now the thickened skull and extended tongue fulfill a fundamental purpose. The downy, like all woodpeckers, has a thick skull to absorb the constant rattle and an adapted, sticky tongue that can yank insects from the inside of a tree or right out of crevices. Their heads sustain whacks 1,200 times the force of gravity. And their tongues actually wrap around special structures in their skulls to accommodate their length. The skulls and brains of downy woodpeckers have been studied by neurobiologists interested in human concussions. Like a Steelers linebacker, downy woodpeckers build up a protein called tau from all the hits, according to a 2018 article in Science magazine. Does downy tau indicate brain damage or an alternative outcome? That piece suggests further avian studies may someday contribute to a better understanding of the football world’s notorious scourge. America’s smallest woodpecker might turn out to be its mightiest as well.

Populations of the downy woodpecker in Pennsylvania are stable, with some 450,000 individuals calling the commonwealth home. Their ability to feel comfortable in any setting, from the woods of the Allegheny Highlands to the backyards of Shadyside, makes them safe from habitat change and degradation.

Email your avian encounters, photos or questions to PQonthewing@gmail.com.