The Sword Over the City

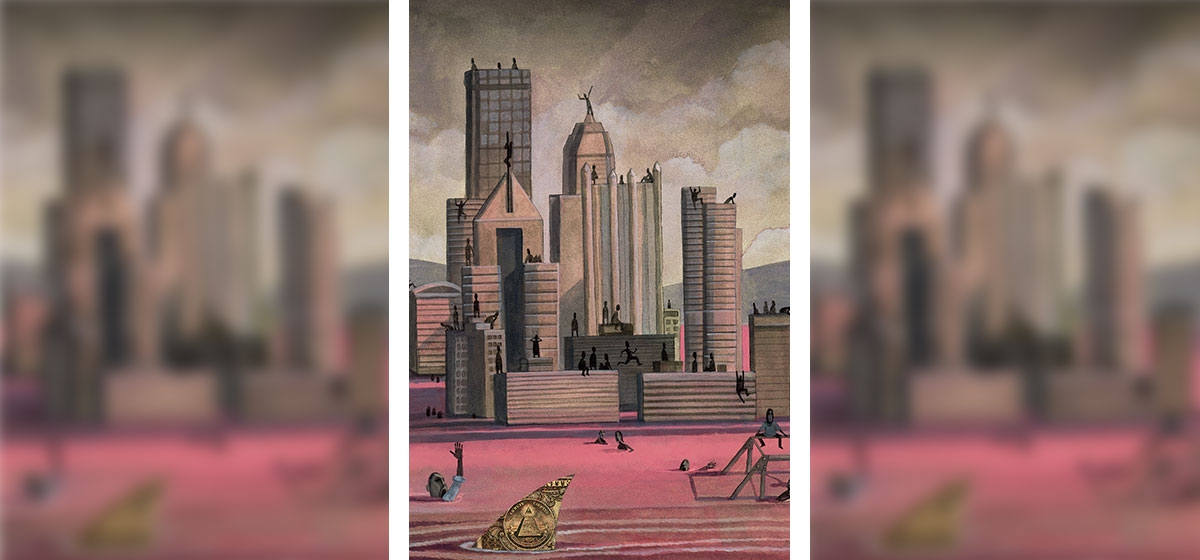

There is a problem in the center of our region that almost defies description in one peculiar aspect. Somehow, the larger it gets, the more invisible it becomes.

The problem is debt.

The City of Pittsburgh owes almost $1.2 billion, most of it borrowed over the last 15 years. It must pay another $400 million to cover former city employee pension and disability payments. Add $400 million borrowed by the rest of city government — “public authorities” such as the Water and Sewer Authority, Parking Authority and Sports and Exhibition Authority. In short, every man, woman and child living in Pittsburgh owes about $6,000, or $2 billion in all.

No other American city of any size is close to what Pittsburgh owes per person and only a handful owe a larger total amount. This is astounding considering that Pittsburgh is now the 53rd largest American city.

If you live in the city, you will pay a share of this debt, one way or another, unless you leave. Should you stay, you are obligated to accept higher and more complex taxes, fewer and lower quality public services and declining economic opportunities. You will live with this burden for at least the next two decades, perhaps longer.

The city cannot soon borrow more money to pay the money it owes — as it did yet again this year — because it has borrowed all that it rationally, morally and legally dares.

The debt is not merely another public policy or political issue. It is the largest crisis that we, collectively, have ever faced. Pittsburgh’s existence is at stake. The money we owe is so massive that it should influence every major public and private dialogue, decision, plan or notion we have or will have for a long time. Yet there is no indication this is the case. Why is that?

“No one is really sure what to do,” said Pittsburgh City Councilman Doug Shields, who has followed the issue for over a decade. “And no one wants to touch it.” Appeals to the only higher authority capable of paying or helping to pay this debt, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, have thus far run their course to nowhere.

Another reason for the deafening silence is that the hole we are falling into gets uglier the further we fall. As the graph shows, fiscally responsible cities dedicate 10 percent of total operating budget to paying debt, while high-performing cities dedicate less. Almost one-quarter of our city’s budget, about $100 million, is a debt payment.

This sum barely puts a dent in the $1.2 billion in Pittsburgh’s bonded debt.

The invisible dead weight on every citizen’s dreams, ambitions and livelihood will grow before it shrinks sometime around 2019. For the next 15 years, the city will have little or no capacity to borrow, while purchases from previous borrowing will lose value or cease to help our city.

We’re already paying for the debt in ways we never intended. Our city does fewer things for its citizens than it did 20 years ago and, in some cases, does them less well. The decay we see now, in rusting bridges, disintegrating sidewalks and poorer quality services is a glimpse of our future. Worse will come.

Local elected and appointed government officials executed the borrowing we authorized. Most of that authorization came in the form of non-votes, which is to say passive support. Throughout the last 15 years, when the city borrowed most of this money, public officials in Pittsburgh typically remained in office as long as they chose. Others not in government brazenly encouraged this borrowing. Voters could have stopped all of this at any time but did not.

Though our choices now appear few and grim, we chose this fate and are free to choose another. However, change will take courage, coordination and contending with challenges that are without precedent in Pittsburgh.

One challenge will be to do something we have failed to do: make choices. Serious financial trouble does not fall from the sky. It accumulates over time. Over a decade and a half we failed to say “no” to anything. We now must get used to spending far less and expecting a lot more. This is going to be very hard, as most of us do not appear to put a high value on excellent government.

A second challenge will be to make every major money choice far more transparent. One indication of how difficult this will be was the recent, modest effort by city council to make some spending available for review online. We need in-your-face openness to make it easy for every citizen to weigh our biggest collective choices against our biggest collective priorities. We must not rely solely on the filtered “best judgment” of elected or appointed officials, many of whom lack the education and background to make such decisions.

Another challenge will be to act as a community and not as a small cadre of the well connected. The burden to pay this bill will be shared by every citizen. We have a history of solving difficult problems as a community. We must see this as one and pull together.

Our biggest and most complex challenge also offers the greatest potential: Grow our way out of this mess. Do you remember how you felt the first time you bought a new car or house? You felt the weight of the world on your shoulders when you signed the loan. Yet something interesting happened. You earned more and more money over the years and used it to pay your debt. The most important lesson was probably to borrow with great care. If you want to borrow more to buy more stuff, you have to earn more money.

Two opposing perceptions obscure our way ahead.

One holds that only the borrower — the city of Pittsburgh — should pay off the debt. The other perceives that Pittsburgh is the fountain. Therefore, everyone from the region who drinks from it should pay to maintain it.

Whatever perception you hold, you must demand action.

If we waver from these challenges, we can say a long and painful farewell to our dream of Pittsburgh as a Great American City. Failure will not come with a bang but with steady disintegration. Great cities, countries and civilizations do, after all, fade into obscurity.