King of the Woodpeckers

The pileated woodpecker burst out of nowhere just as I thought my students’ field exam was over. As soon as we were aware of it materializing from the canopy of a tree on a green at the Pittsburgh Field Club, it flew like a black bolt into denser woods and disappeared again. A great last bird for an exam in ornithology.

My students and I had traipsed through the forest surrounding the golf course in Fox Chapel to a secluded pond that hosted a great blue heron breeding colony, belted kingfishers, Baltimore orioles, and the occasional migrating wood duck. The pileated woodpecker was equally at home there, drilling characteristically deep, often rectangular holes into decaying or dead wood trunks in its ongoing search for ants, larvae, and other insects. In fact, all the wooded slopes of Pittsburgh’s river valleys are good territory to spot this largest of North American woodpeckers, though a nice block of suet can draw them into a backyard.

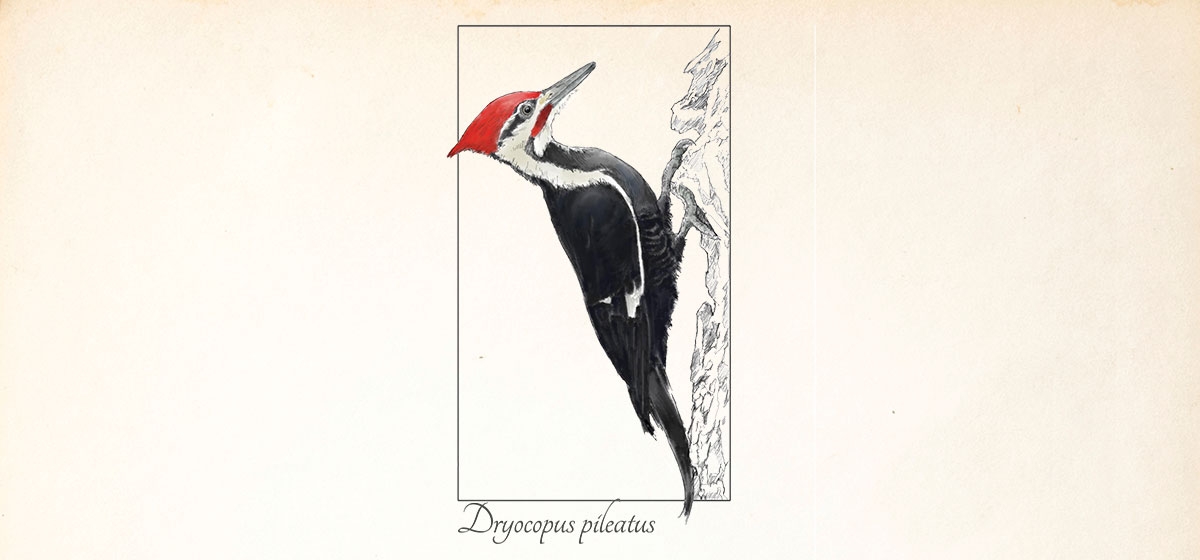

Roughly the size of a crow, the pileated woodpecker is black and white with a jarring red crest. Except for the blue and white jump suit, the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker is a reasonable stand-in, most reminiscent to the living bird in its urgent, cacophonous vocalizations. The real woodpecker’s voice sounds through the forest along with its rat-a-tat-tat drumming. Unless it’s exploring the wood siding of your house. Which makes this avian giant less than welcome!

Resident across the eastern United States and across Canada to narrow bands on the West Coast, the pileated woodpecker is a stunning if fairly uncommon year-round denizen of our woods. Pairing for life and non-migratory, males and females join up to drill cavernous nest holes, a foot or two deep in a tree, in which are laid three to five plain white eggs each spring. (The eggs of cavity nesters are usually white and unadorned, as no coloration or camouflage is needed.) After a fortnight plus of incubation, altricial, helpless chicks hatch and spend about 30 days eating regurgitated meals, growing feathers, and getting used to the bright world just beyond the nest hole. Fledglings spend the next several months around mom and dad before looking for their own territories. With the regrowth of eastern forests, the population of pileated woodpeckers is strong and has been increasing for over 50 years, so suburban and even urban birds might be spotted if the territory is expansive enough. Most pairs need 150–200 acres and defend their home turf with vigor, tolerating conspecific guests in non-breeding months.

And those woodpeckers drumming on your house? Most of the time it’s a smaller, cousin species like a downy woodpecker, hairy woodpecker, or northern flicker and even then, that’s pretty uncommon. If you’ve had one of the big guys drilling on your home, or if you have photographic or anecdotal evidence of the same, email me at PQonthewing@gmail.com.