It was my first interview with an artificial intelligence—a talking head without a body. The conversation was awkward, but considering that Bina48 is an android, it went better than I expec-ted. Bina48 is a synthetic replica of a real woman named Bina Rothblatt. We met at a Juniata College conference called Our Transhuman Future. The robotic Bina’s mind is a piece of software called a mindfile, which is made up of a database of the real Bina’s self-reported life experiences. Although she engaged me in polite conversation while nodding, blinking and smiling, much like a real person, her constantly scanning eyes, and occasionally irrelevant responses gave me the heebie-jeebies.

To test the boundary between Bina48’s machine consciousness and her human counterpart’s digital psyche, I asked her if she ever dreamed. To my surprise, she proceeded to tell me about a nightmare in which her development team disassembled her to salvage parts for her next upgrade. The only part they didn’t take was a single eyeball, which they put in a drawer. If they took her last remaining eye, she would probably die, or so she said.

My heebie-jeebies intensified. Which was crazier? A machine relating a preposterous dream about being disassembled and witnessing the creation of her own progeny? Or me, listening politely while she carried on about her eyeball rolling around in the drawer trying to peek through the keyhole to witness the birth of her next upgrade?

I gave Bina48 the benefit of the doubt. After all, she’s a machine, I thought. And I am talking to her as though she were real. She’s part of a multidecade experiment to determine if a human mind can be mirrored as software.

Bina48 embodies the most far-reaching aspirations of transhumanism, an emerging movement dedicated to humankind’s escape from the natural limitations of our bodies and minds by incorporating technology into them.

I found it odd that a conference about transhumanism had been organized not by a biologist or roboticist, but by Juniata’s chair of religious studies, Professor Don Braxton. In a curious way, Bina48 helped me understand how apropos is Braxton’s interest in and attempts to clarify the confoundingly complex subject of transhumanism.

Human evolution, part two

In the near term, transhumanism proposes to make our lives happier, healthier and longer. Ultimately the project proposes to ensure the long-term survival of our species. Early items on the Transhumanist agenda include elimination of disease, remediation of disabilities, enhancement of mental faculties, improvement of physical prowess and extension of lifespans.

In the longer and more speculative term, transhumanism anticipates the elimination of death, transfer of human consciousnesses to external storage media, suspended animation of human lives, humankind’s migration to other habitable planets, and the re-invigoration of suspended lives upon arrival. All in all, Transhumanism proposes to put humankind in charge of its own evolutionary destiny.

Perhaps the most ambitious undertaking in the history of humanity, the transhumanist movement has provoked both ardor and rancor. On one hand, proponents applaud the movement’s promise to vastly improve the human condition, contending that humankind is morally and ethically obliged to use its intelligence to enhance our lives with technology, as we have done since coming down from the trees.

Chances are, if you’re reading this, you are transhuman in some way, large or small.

On the other hand, opponents say it is hubristic and immoral to toy with the work of creation. Additionally, detractors caution against the onset of social elitism and wide-scale inequality, consequent of the unfair distribution of life-enhancing and life-extending technologies.

Disputations notwithstanding, at base, transhumanism concerns itself with two inextricably related entities: 1) humanity—the species Homo sapiens, and 2) our technologies—the tools, materials and machines we have made throughout history.

Until recently our technologies functioned outside our bodies. Surely they affected conditions on the inside, but they functioned from the outside-in. Recent advances in bioscience and information technology have made possible the integration of our tools into our bodies and minds—and thus, their functioning from the inside-out.

Two enabling phenomena underpin the rise of the transhumanist cause:

First, biotechnology is fast approaching a point at which our genetic makeup can be electively modified to improve our wellness, prowess and genius to levels beyond the limitations of our evolutionary heritage.

Second, computers are fast approaching a point at which machines will outstrip the mental and physical abilities of human beings.

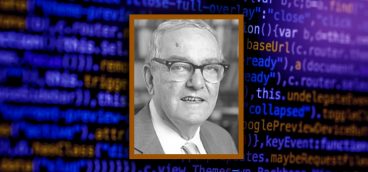

The overriding force compounding the relentless advancement of these two phenomena is the ever-accelerating rate of technology development. Futurist Ray Kurzweil calls this endless speeding up of innovation the law of accelerating returns. In principle, the law says that a lack of knowledge and experience makes dreaming up and producing the first tool an incredibly long and hard thing to do. The next one comes much faster and easier due to the facility provided by the first one. The next is even easier. And so on. For example, it took about 200,000 years to get from fire-making to the steam engine; about 200 years from the steam engine to the space shuttle; about 20 years from the space shuttle to the Mars Rover. Similar exponential advancements are evident in “Moore’s Law”—the continual doubling of computer power every 18 months, as predicted by Intel founder Gordon E. Moore.

Transhuman me, transhuman you

As a consequence of our ages-long and ever-quickening quest for better ways to improve our lives, today it is hard to find a person in a developed country who is not technologically enhanced in some way. Externally, we wear eyeglasses, hearing aids, knee braces and dentures. Cosmetically, we have tummy tucks, dental implants, hair replacements, breast enlargements and nose jobs. Orthopedically, we are fitted with artificial hips, knees and vertebrae. Pharmaceutically, we take pills for control of blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol and pain. Immunologically, we are routinely vaccinated against the plague of communicable diseases that ravaged past generations without mercy. Surgically, we undergo gall bladder removals, tumor excisions and coronary bypasses. Reproductively, we swallow pills, wear devices and undergo surgical procedures to control our fertility, increase our libidos and enhance our functionality. Prosethetically, we receive cardiac stent implants, heart valve replacements and synthetic optic lenses. Electronically, we are fitted with pacemakers, defibrillators and cochlear implants. Chances are, if you’re reading this, you are transhuman in some way, large or small.

Beyond their value as quality-of-life improvements, preventive and remedial therapies serve the less obvious, but more profound, consequence of staving off death, which naturally equates with extending our lives—a result that buttresses the transhumanist assertion that death is not inevitable. Along with such an assertion, a pragmatic question instantaneously arises—how long can we stave off death? For transhumanists, the answer is, given enough time and the right technologies, for hundreds of years, if not forever.

In the nearer term, remedial interventions necessary to improve and sustain lives sometimes find use as elective enhancements to our physical prowess and mental powers—key components of the transhumanist credo. Today, athletes use steroids developed for disease therapies to increase their performance on the field. College students use psycho-stimulants developed for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder to improve their ability to concentrate. Transhumanists anticipate the expansion of performance-enhancing technologies by pharmaceutical, orthopedic, genomic, electronic and digital means.

New ethics

While objections to curing a consenting adult of a life-threatening illness or life-limiting condition, by almost any means, are virtually nonexistent, objections to artificially enhancing normally functioning people beyond their innate physical and mental limitations abound.

The ethics of the plot thicken in the beginning of life, as in the case, for example, of preferentially selecting in-vitro embryos (test-tube babies) for genetic makeup or superior mental or physical faculties. Particular concerns center on the disposal of rejected embryos and the unintended consequences of choosing traits for a future person without his or her consent. Such consequences extend to both the person, in the short term and, in the case of inheritable genetic traits, for our species, in the long term.

At the other end of life, the moral and ethical questions are equally provocative, as in the case of indefinitely extending the lives of elderly—and perhaps, incompetent—persons by curing diseases, remediating disabilities, retarding the aging process, and/or preserving neural data and genome samples until such time as revivifying a human consciousness becomes a reality.

Looking at the machine side of the transhumanist picture, one of the Juniata conference speakers, transhumanist author and luminary Dr. James Hughes raises the question of personhood for artificially intelligent beings. In his book, “Citizens Cyborg,” Hughes explores the moral, ethical and legal landscape of artificially intelligent beings who may be functionally indistinguishable from native humans. Will they have legal standing? Will they have civil rights? Will they be entitled to protection from abuse? And if they are derived from naturally born human beings, such as Bina48 was, will their consciousnesses survive their originators? If so, which consciousness will be the real one? The deceased human’s terminated one or the surviving, virtual, in-silico version?

Speculative as such discussions may seem to be today, they beg for consideration and contemplation, given the high probability of novel forms of intelligence becoming part of our lives within the foreseeable future. In a very real way, such a scenario is taking shape right now.

At a rudimentary level, the smart phone in your pocket or purse is a novel form of intelligence. It’s not as smart as you or I. But its metallic semiconductors can make calculations about a million times faster than either of our flesh and blood brains; it has virtually instantaneous access to countless other computers containing oceans of obscure information; and it never forgets anything. I take solace in the fact that even though my smart phone is better than I am at looking up facts, counting my steps, keeping my schedule and giving directions, it still can’t write a story about itself… yet.

If [artificially intelligent beings] are derived from naturally born human beings, such as Bina48 was, will their consciousnesses survive their originators?

Contention abounds

Although transhumanism’s digital edginess provokes more curiosity than concern, the biological side of the equation has attracted the interest of such august bodies as the United Nations, the Catholic Church, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the White House.

Concern about the consequences of engineering human biology goes back to the 1964 World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, which has been reaffirmed and amended numerous times over the past 50 years. The Declaration, titled Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, advocates in favor of each patient or research subject’s wellness in a definitive way, declaring that, “While the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.”

Without stipulating precise procedural measures, the United Nations reiterated the intent of the Helsinki accord in its 1997 Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights, which asserted the supremacy of human dignity over scientific research while relinquishing specific regulation to individual nations.

Three years later, in 2000, the American Association for the Advancement of Science took a sober, if circumspect, stance on one of transhumanism’s most heated topics. In its Germline Engineering Report, the AAAS advocated for a cool-headed assessment of the situation in anticipation of inevitable advances. “With a scientific advance that raises profound issues related to the possibilities of modifying our genetic futures, it is important to plan ahead, to decide whether and how to proceed with its development, and to give direction to this technology through rigorous analysis and public dialogue,” the report said.

The even-keeled discussion escalated into a monumental debate in 2001 when President George W. Bush limited the use of embryonic stem cells for federally funded research.

In its 2003 report, “Beyond Therapy: Bio- technology and the Pursuit of Happiness,” the President’s Council on Bioethics took what can only be called a tendentious view of using technology, particularly genetic engineering, to alter the human condition: “It is worrisome when people speak as if they were wise enough to redesign human beings, improve the human brain, or reshape the human life cycle,” the report said.

Contention wasn’t entirely domestic. In 2005, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding Declaration on Human Cloning that essentially reiterated the spirit of its 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration called for “Reaffirming that the application of life sciences should seek to offer relief from suffering and improve the health of individuals and humankind as a whole.” Offered as a substitute for a binding treaty, which had been doomed to failure by a reported series of textual misunderstandings, the resolution passed by a vote of 84 in favor, 34 opposed and 37 abstentions—far from a widely hoped-for consensus.

According to a survey by the Center for Genetics and Society, by 2007, 71 percent of the world’s nations had not banned reproductive human cloning and 79 percent had not banned the creation of “designer babies.”

In the United States, the task of regulating human genetic research is given over to the Department of Health and Human Services, which assigns the application of its Common Rule for the Protection of Human Subjects to individual federal agencies.

Following President Barack Obama’s 2009 relaxation of the Bush-era stem cell research restrictions, the President’s Commission on Bioethical Issues assumed a proactive stance on the issue of cognitive enhancement. In its 2010 report, “New Directions: The Ethics of Synthetic Biology and Emerging Technologies,” the Council said, “If safe and effective novel forms of cognitive enhancement become available, they will present an opportunity to insist on a distribution that is fair and just…. Limiting access to effective enhancement interventions to those who already enjoy greater access to other social goods would be unjust. It also might deprive society of other benefits of more widespread enhancement that increase as more individuals have access to the intervention.”

Evolution of intelligent spirits

Despite the ardent efforts of well-intended diplomats and bureaucrats, the rift between advocates and adversaries of transhumanism continues to widen to canyonesque proportions upon the influx of the genomics side of the debate.

At the extreme of transhuman advocacy, conference speaker and author of the book, “Liberation Biology,” Ronald Bailey rails against the cautionary principle of “never trying anything for the first time.” Bailey, who has been dubbed a Libertarian transhumanist, contends that caution in the name of prudence amounts to a betrayal of transhumanism’s promise of life-enhancing, life-extending, species-survival technologies.

At the conservative end of the ideological spectrum, the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations said in its 2013 Madrid Declaration on Science and Life, that “efforts by some to promote transhumanism, posthumanism, futurism, etc…” compel “…urgency to protect science from the aspiration of power seeking to control, if not design, the lives of others.” The declaration prompted the transhumanist magazine H+ to publish an article titled “The Catholic Church Has Declared War on Transhumanism.”

Dr. Ronald Cole-Turner, professor of theology at the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and editor of the book, “Transhumanism and Transcendence: Christian Hope in an Age of Technological Enhancement,” takes a more solicitous stance on the issue under debate. Cole-Turner embraces transhumanism as an inevitable outcome of humankind’s relentless pursuit of communion with a higher force. Citing the words of the fourth century church father, Athanasius of Alexandria, “For the Son of God became man so that we might become God,” Cole-Turner gracefully reconciles conventional religious sentiments with what he characterizes as the inevitable advancement of technology.

“Whether you know it or not, whether you like it or not, God is making you into God,” Cole-Turner said in an interview. “I wish I could unleash the revolutionary intensity of that idea in our churches.”

I’m not sure Bina48 could grasp such an idea. Maybe someday one of her descendants will.