A Very Short History of Pittsburgh

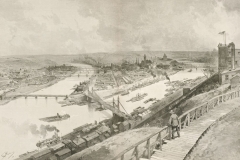

Geography comes first. Close upon the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, one gets a sense of westward flowing waters, but a map of Western Pennsylvania shows the Allegheny flowing south and the Monongahela north, almost at right angles to the Ohio.

A fourth river, the Potomac, comes into play by bringing the coast of Virginia close to the Monongahela and allowing for some tough navigation to connect Pittsburgh with the Atlantic Ocean. Lastly—the mountains. The western slope of the Alleghenies lies some 40 miles from the Point. From there, it’s a straight 1,500-mile shot to the Rockies. Pittsburgh not only faces but opens the great heartland of America. Before the canals and railroads, the Ohio and Mississippi river systems were the interstate highways of their day.

By the mid-eighteenth century (1751) there were three claimants to southwestern Pennsylvania: the French, the English and the Indians. Geographically the French were in the strongest position. They controlled two great waterways that drained the North American continent: the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi. They were weaker but still dominant in the Ohio valley. The best passage through the Alleghenies was up the Potomac to the Monongahela, and then down the Ohio. Lucrative trade and rich soil were an irresistible draw for the expanding English colonies.

It was Virginia’s soldier aristocrats rather than William Penn’s Quakers who first breathed life into southwestern Pennsylvania. In 1747, a group of prominent Virginians, including Lawrence Washington, half-brother of George, founded the Ohio Company. They applied to the English king for a grant of 200,000 acres. Soon after receiving the grant, the Ohio Company began exploiting their new lands. The French, under the firm hand of the Marquis du Quesne in Montreal, responded, establishing Fort LeBoeuf on French Creek, within striking distance of the three rivers. Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia (an Ohio Company investor) sent young George Washington to LeBoeuf to protest. Out-manned and outgunned, Washington protested and left in December 1753. Round one to the French.

Early the next year, Dinwiddie sent an Ohio Company party to the forks of the three rivers to build Fort Prince George, the first English fort west of the Alleghenies. That April, a French army of 500 confronted the handful of men at the fort; they promptly surrendered. The French renamed it Fort Duquesne over which the fleur-de-lis was to fly for the next three years. Round two to the French.

Dinwiddie raised new forces, and an advance party under George Washington pushed through to Great Meadows, 50 miles southeast of the fort. After a fateful skirmish at Fort Necessity, Washington surrendered in July. Round three to the French.

It became obvious that the Ohio Company, even with the help of Virginia and Pennsylvania, was not going to drive the French Empire from the Ohio Valley.

General Edward Braddock was the first of a long line of unfortunate choices as British commanders in America. He assembled a force of 2,200 regulars and colonials and on July 9, 1755, marched them to a stunning defeat against an inferior force of French and Indians on the site of today’s Edgar Thomson Works, 10 miles east of the Point. The loss was staggering—456 dead and 421 wounded. Round four to the French. Things were not looking good.

Fortunately for the American colonists, the conflict in the Ohio Valley—our French and Indian War—was a small part of the global struggle between France and England, known as the Seven Years War (1756–1763). It pitted England and Prussia and their indomitable leaders William Pitt the Elder and Frederick the Great against the rest of Europe. Pitt assumed full power in 1757 and declared: “I can save this country and nobody else can.” He was true to his word. The English fleet swept the French from the seas and destroyed France’s colonial power in America, Africa and India.

The American piece played out under General John Forbes, who was assigned the retaking of Fort Duquesne. Forbes assembled an army of 6,000, including 2,000 regulars, 2,500 Pennsylvanians, and 1,500 Virginians. The force was overwhelming, but the French still had some fight left in them. An impetuous Major James Grant rushed ahead with a detachment of 800 at a hill near today’s Allegheny County Courthouse. Though the French and their Indian allies defeated Grant in a smaller reprise of Braddock’s Field, Grant’s name lives on in Pittsburgh’s own Champs d’ Elysees: Grant Street. The capture of Fort Duquesne was anticlimactic. The French, weakened by serial defeats in Quebec and on Lake Erie simply abandoned the fort. Round five to the English in a TKO.

Forbes wrote Pitt: “I have used the freedom of giving your name to Ft. Duquesne.” Thus we became Pittsburgh with an official birthday in 1758.

There was an inevitability to the English triumph in America. Had there been no Pitt, or had Braddock been a better general, the English triumph may have come later or sooner, but it was destined to come. One word tells the story: population. The French, forced to defend a frontier running from Nova Scotia to the Gulf of Mexico, had a scant 80,000. The English colonies had a compact population of 1.25 million, which would double in 20 years. The numbers alone destined the English colonists to pop the cork at the Point and sweep the French, Spanish and Indians back in an irresistible floodtide.

The birth of industry

After the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, commerce and industry eventually replaced politics as the storyline in Pittsburgh history. But one final political chapter had yet to play out. In 1791, Congress adopted an excise tax on whiskey. In Western Pennsylvania, the tax bit especially hard. One in five farmers operated a still. Additionally, in the largely self-sufficient agricultural economy, cash was scarce while whiskey was plentiful. The tax itself was not unreasonable. The rub came as the farmers sold their whiskey not for cash but bartered it. In short, they had a “liquidity” problem. The cry went up that the tax was unjust and the farmers defied the newly formed national government. George Washington and the ever-energetic Alexander Hamilton responded with overwhelming force. Washington personally led 13,000 militia partway to Pittsburgh, and Hamilton negotiated a settlement. It was a critical victory for the young republic.

Abundant natural resources—including wood, coal, limestone and sand, along with flax and cotton—coupled with the mountain barrier to Eastern imports drove Pittsburgh to early self-sufficiency. The river network meant raw materials could be shipped to Pittsburgh, aggregated through simple manufacturing and shipped out.

In the period from 1790 to 1810, arguably the most important industry in Pittsburgh was boat building. The rich forests of Western Pennsylvania and fast river transit landed the required materials at the perfect location at the head of the Ohio. Two principal types of boats were built in Pittsburgh. The flatboat was used exclusively for down-river running. Length varied from 20 to 100 feet and width from 12 to 20 feet. Construction was simple; a pile of logs and a bucket of nails and you were good to go. Prices varied from a dollar to $1.50 a foot. The average boat carried 50 tons. The journey to New Orleans was a four-week, one-way trip. Once there, you sold the boat for the value of the lumber.

Keelboats were used for upriver hauls. Trips from New Orleans to the Point took four months. Lewis and Clark began their fabled trip to the Pacific in a Pittsburgh keelboat in 1803. The same year, Pittsburgh built the 170-ton brig “Dean” which sailed from Pittsburgh down the Mississippi and across the Atlantic to Liverpool. And in 1811, Nicholas Roosevelt, a partner of Robert Fulton, launched the first steamboat on Western waters. The “New Orleans” carried 450 tons and made the trip to Louisville in 64 hours. Soon, steam power spread to gristmills and iron rolling mills. By 1812, the local firm of Oliver and Evans was manufacturing steam engines.

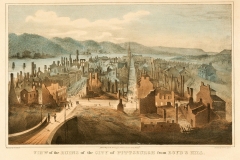

Politically, the region began to take shape when, in 1788, Allegheny County was created from parts of Washington and Westmoreland counties. The City of Pittsburgh was incorporated in 1816, with merchant Ebeneezer Denny as mayor. The best sign of the city’s gradual transformation from a commercial to a manufacturing center was a visitor’s description in 1818: “Dark dense smoke and a hovering cloud of vapor.” It would get much worse over the next 125 years.

The period between the end of the War of 1812 (1814) and the outbreak of the Civil War (1861) saw a pronounced shift in Pittsburgh’s economy from commerce to industry. Part of it resulted from several challenges to Pittsburgh’s near monopoly on western trade. As the population west of Pittsburgh surged, down-river cities, such as Cincinnati, Louisville and St. Louis, began to challenge Pittsburgh as supply points near the frontier. In 1825, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson River to Buffalo, spurring the growth of Cleveland, Detroit and Chicago. This was not trade that Pittsburgh lost—she never had it— but it did put a damper on future commercial growth. A far greater threat was the decision of the U.S. Congress to terminate the National Road (today’s US 40) at Wheeling on the Ohio, bypassing Pittsburgh. After its completion, 5,000 Conestoga wagons from Baltimore unloaded annually at Wheeling. For a while it looked as if Wheeling might offer a strong challenge to Pittsburgh. But manufacturing momentum favored Pittsburgh, and Wheeling eventually languished.

And now for the geology.

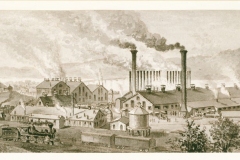

Many of Pittsburgh’s industries required iron, and the heart of its developing economy rested upon that metal. When Charles Dickens visited in 1842. he observed: “Pittsburgh is like Birmingham in England… and is famous for its iron works.” Iron production began in the hinterlands, closer to sources of wood for charcoal; adequate veins of iron ore were found in Fayette, Somerset and Washington counties. Local foundries turned out simple shapes, nails and farm implements while supplying a host of machinery manufacturers.

In Samuel M. Kier (1813–1874), Pittsburgh claimed a multifaceted industrialist in canal boats, fire brick, medicines and, most important, oil refining. When oil began to seep into his father’s salt wells in Tarentum, Kier attempted to market the then-unwanted fluid. The goal was to replace the whale oil used in lamps, but the smoke and odor made this new, crude oil unacceptable. Kier rose to the challenge of refining it by distilling the crude in a five-barrel still built at a site 100 feet from today’s U.S. Steel Building. Through Kier’s inventive genius, Pittsburgh was the oil refining center of the nation, before John D. Rockefeller consolidated the industry.

The Civil War gave great impetus to Pittsburgh’s nascent industrial base. Pittsburgh rapidly became the arsenal of the Union. The Fort Pitt Foundry cast over 3,000 cannon, including the world’s largest at 20 inches. The cannon that armed the “Monitor,” the Union’s first ironclad ship, was cast in Pittsburgh.

The golden age

The 40-year period from 1870 until 1910 marked Pittsburgh’s Golden Age. Favorable geography, unique natural resources and a super-abundance of entrepreneurial talent lifted Pittsburgh to a position of national and international prominence never seen before or since. Pittsburgh’s growth is a story of heavy industry, specifically steel. Population statistics speak to Pittsburgh’s dynamism during this period. The city’s population grew sixfold in those 40 years, from 86,076 to 533,905. Allegheny County nearly quadrupled, to 1,018,463 residents. The local population growth rate doubled that of the nation. In 1900 the value of manufactured products in Pittsburgh was more than Cleveland and Detroit combined.

How did Pittsburgh become the steel capital of the world? First there was iron. Pig iron is the product of the smelting process: the reduction of iron ore in a blast furnace. It has a high carbon content and is less malleable than steel. From Colonial times until 1850, iron production was localized, based on iron ore sources and ample forests for charcoal—the smelting fuel of choice. As demand for iron surged from 1840–1870, larger tracts of forest land were required to provide charcoal, and deforestation became a problem. Charcoal was first replaced by anthracite (hard coal) from Northeastern Pennsylvania, but by 1875 bituminous (soft) coal in the form of coke from Southwestern Pennsylvania provided over 50 percent of blast furnace fuel. Coke is prepared when great heat is applied to coal kept out of direct contact with air; it is nearly pure carbon.

Once again, the region’s geology was essential to success. The Connellsville coal seam is part of the famous Pittsburgh coal bed which extends throughout southwestern Pennsylvania. The Connellsville seam runs for 60 miles from Latrobe in the north to 10 miles south of Uniontown in a south/southwesterly direction. Connells-ville lies at its center. The seam varies between 2.5–3 miles across and occupies 180 square miles, or 115,000 acres.

The seam itself was a generous 8–10 feet thick with an average overburden of 60–150 feet. This coal was almost free of slate and sulfur, so the resultant coke was porous and hard, allowing for stability in the furnace stack. It was a near-perfect fuel.

Coal was transformed in the Connellsville fields by means of beehive ovens, averaging 7 feet high and 12 feet in diameter. They were cheap to build. During its period of prime production (1880–1935), the Connellsville region shipped 500 million tons of coke, requiring 770 million tons of metallurgical coal. At its peak, 39,000 beehive ovens produced over 20 million tons of coke annually. The direct and indirect wealth produced by this bounteous gift of nature far exceeded the value of all the gold and silver ever mined in the U.S.

Cheap coke and coal made the concentration of the steel industry possible. Half an acre of Connellsville coal produced the fuel equivalent to 2,000 acres of forest land.

In addition to its riches in coking coal, three interrelated factors destined Pittsburgh to be the nation’s steel capital: the Bessemer process, the railroads and Andrew Carnegie. The Bessemer steel-making process consisted of air blown through molten iron in a five-to-seven-ton, egg-shaped Bessemer converter. It was the joint work of Englishman Henry Bessemer and American William Kelly. The oxygen in the air decarbonized the iron, converting it to strong, workable steel. The Bessemer process was widely adopted in the U.S. between 1865 and 1875, and it made mass production of steel possible. The iron industry soon became the steel industry. Fortunately, Bessemer-driven steel production coincided with an insatiable demand from U.S. railroads for steel rails. In 1860, U.S. railroad trackage was a modest 30,000 miles. It doubled by 1870 and increased eight-fold by 1900.

Into this confluence of mass production and mass market walked one of the most extraordinarily talented figures in American business history, Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919). After a meteoric rise at the Pennsylvania Railroad, he left to attend to a host of business ventures he had financed while still employed by the railroad. His mentor, Thomas A. Scott, and Pennsylvania Railroad President J. Edgar Thomson were co-investors in most of these ventures. The Pennsylvania Railroad was invariably the major customer in those days, when conflict of interest was an alien concept.

In 1872, Carnegie organized a syndicate to construct a steel plant of 100,000 tons capacity on a site in Braddock. Scott and Thomson were in from the start. The plant was named the Edgar Thomson Works. It was one of the first plants designed with Bessemer converters specifically to make rails—a single-purpose plant. Carnegie made an extraordinary hire in Captain Bill Jones, the best operating man in the business. In its first year of production, the plant was profitable and was the lowest-cost rail producer in the nation. Nobody could sell rails like Carnegie. He used his pricing power to telling effect.

One can scarcely overestimate the importance of the railroads in American industrial history and in the growth of the steel industry. Until 1890, the railroads were pretty much the market. Not only rails, but locomotives, rail cars, bridges and tunnels added to the tonnage. In the ’70s and ’80s, Pittsburgh was a hotbed of steel start-ups. Two notable efforts at Homestead (1881) and Duquesne (1890) succumbed to Carnegie’s sharp, competitive thrusts and were absorbed into the larger company.

Carnegie didn’t have it all his own way, however. Jones & Laughlin Steel dated from before 1855. It never attempted to meet Carnegie head on in rails but sidestepped him by producing a variety of other products, including shapes, nails and bars. By the end of the century, J & L produced 650,000 tons of steel and went on to become the fourth largest steel producer in the United States.

By 1900, fully integrated in both iron ore and coal, Carnegie Steel was the country’s largest steel company with 3 million tons of capacity. In 1901, J.P. Morgan consolidated the steel industry with Carnegie and seven other major companies into the giant U.S. Steel Company with a capitalization of $1.4 billion—the largest private company in the world. It controlled 60 percent of U.S. steel production, with more than 40 percent coming from the Carnegie properties. By 1910, Pittsburgh produced 25 million tons of steel; more than 60 percent of the nation’s total. It was the high-water mark for Pittsburgh’s share of national steel production.

During this Golden Age, Pittsburgh was a seething cauldron of entrepreneurial activity. Matching Carnegie in industrial prominence was the Mellon family. In 1870, Judge Thomas A. Mellon established a private bank, T. Mellon & Sons. He was soon joined by his third surviving son, A. W. Mellon (1855–1937). Through financial acumen rivaling J.P. Morgan, he built the Mellon Bank into the 13th largest bank in the country. In 1889 he and his brother, R.B. (1858–1933), financed the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, later Alcoa—for over 100 years the largest aluminum company in the world. In 1900, the Mellons, along with nephew W.L. (1848–1949), founded the Gulf Oil Company. It eventually accounted for 40 percent of the family fortune and became one of the “seven- sister” international oil companies. Mellon’s fingers were everywhere. In addition to his three largest holdings, A.W. founded Koppers, Carborundum, Union Steel Company, Standard Steel, Pittsburgh Coal, McClintic-Marshall and a host of other sizable companies.

George Westinghouse (1846–1914) moved to Pittsburgh from Schenectady, NY in 1873. Pittsburgh beckoned because it was a rail hub with low steel costs and abundant metalworking talent. He patented his revolutionary air brake in 1869 and built Westinghouse Air Brake into one of the nation’s most successful and lucrative corporations. As an inventor (371 patents) Westinghouse stands second only to Thomas A. Edison. In 1886, he founded the Westinghouse Electric Company—at its peak the nation’s 13th largest industrial company.

Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919) built a vast fortune on the mineral wealth of the Connellsville coal seam. Known as the Coke King, he was originally financed by Judge Mellon and became a close confidant of A.W. Mellon. In the ‘80s, Frick needed money and Carnegie needed coke. Carnegie bought a controlling interest in the H.C. Frick Coke Company and Frick ran the entire Carnegie operation. Despite a final rupture, it was a win/win relationship.

Henry J. Heinz (1844–1919) founded the precursor of the H. J. Heinz Company in 1869. The Heinz Company was the odd man out as a branded consumer products company in a town totally dominated by heavy industry.

By 1970, Pittsburgh would have the distinction of being the third largest corporate headquarters city in the United States. With but few exceptions, all these companies or their antecedents were founded during the period between 1870– 1910: Alcoa, Allegheny Ludlum, Blaw-Knox, Consolidation Coal, Copperweld Steel, Crucible Steel, Dravo, Fisher Scientific, Gulf Oil, Harbison Walker, H. J. Heinz, Jones & Laughlin, Joy Manufacturing, Koppers, Mellon National Bank, Mesta Machine, Mine Safety Appliance, National Steel, Pittsburgh Chemical, Pittsburgh National Bank, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Pittsburgh Steel, Rockwell International, United Engineering and Foundry, Universal Cyclops, United States Steel, Westinghouse Air Brake and Westinghouse Electric. With the exception of the two banks, Heinz and a couple of light manufacturing companies, it was heavy industry all the way.

In only 40 years, the industrial growth of Pittsburgh was breathtaking. It was an era of unprecedented dynamic entrepreneurialism. For those at or near the top of the heap, it was a glorious time, but for the vast majority it was a burden to be born. Most work in the mills was 12 hours a day, six and seven days a week. Enlightened employers such as Heinz and Westinghouse were the exception.

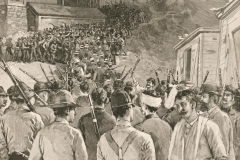

Two of the most violent strikes in U.S. labor history occurred during this period. The more famous of the two is the Homestead strike, compounded by Carnegie’s malicious attempt to dodge all personal responsibility. The more violent of the two was the great railroad strike of 1877. In it, over 20 people were killed and property damage was over $5 million ($100 million in today’s dollars). It was all for naught; unions were not to be a factor until the 1930s.

The long slide

Pittsburgh’s Golden Age had developed an industrial economy that was the envy of the world. The major enterprises launched then drove the Pittsburgh economy to new heights for the next 50 years. So strong were these Pittsburgh corporations that they carried nearly the entire weight of the local economy. The entrepreneurial era became the managerial era, and Pittsburgh was a quintessential “company town.” For both white- and blue-collar job seekers, Pittsburgh had a host of good jobs, and with the advent of Pittsburgh unionism in the late 1930s, Pittsburgh’s blue-collar jobs became even more desirable.

Unfortunately, there was a downside to Pittsburgh’s over-specialization in steel and heavy industry. Because the jobs were so attractive, they drew potential entrepreneurs away from smaller businesses.

Again, population tells the story. In 1930, the population of Pittsburgh peaked at 699,817. By 2000, it was 343,600— roughly half. Some of this was migration to the county. But here the story is equally bleak. In 1938, Allegheny County had a population of 1,374,410 and in 2000, 1,277,700. Between 1910 and 2000, the U.S. population increased threefold, while Allegheny County lost 9 percent of its population. In 2000, Pittsburgh had the second oldest demographic profile of any U.S. metropolitan county, behind Dade County, FL. Despite a static population, by the mid-20th century, good jobs in Pittsburgh’s heavy industry manufacturing sector remained plentiful. Economic development was not a high priority. What was a high priority was Pittsburgh’s environment. When Pittsburgh exited World War II in 1945, the Point at the confluence of the three rivers was a tangle of railroads and warehouses. Through a combination of the steel mills and the universal use of soft coal for home heating, the sky was often black at 9 a.m. (If you think Beijing is bad today, you should have seen Pittsburgh in 1945.) Despite a vital economy, Pittsburgh was dying at its core and in danger of losing the head offices of the companies that made it great.

Two very different men formed a compact and a shared vision to put Pittsburgh back on track. David L. Lawrence (1889–1966), mayor of Pittsburgh from 1946 to 1959, was the foremost political figure this city ever produced. Richard King Mellon (1899–1970) the son of R.B. Mellon, was the chairman of Mellon National Bank, and through his vast holdings was the natural leader of the Pittsburgh business establishment. With the able assistance of Wallace Richards and Arthur Van Buskirk, and through the instrument of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, they gave birth to what became known as the Pittsburgh Renaissance. Smoke-control legislation was passed, the skies cleared, and the industrial jungle at the Point was razed and replaced with a park and several new office buildings. In a brief 15 years, the face of Pittsburgh changed dramatically.

Ironically the year Lawrence left office in 1959 saw the first serious rupture in Pittsburgh’s industrial underpinnings. It came in the form of a crippling 116-day, industry-wide, steel strike. It opened the door to the first major influx of imported steel. It was a problem that would eat away at the industry for the next 40 years, eventually bankrupting 29 steel companies. Still, the Pittsburgh industrial behemoth hummed along very well into the 1970s, but beneath the surface, the tectonic plates of fundamental economic change were grinding on. Pittsburgh-based steel companies were expanding capacity but not in Pittsburgh. Light sheet steel for appliances and automobiles was their most important market, and it was best served from steel plants in the Midwest.

By the late 1980s, over 75 percent of the steel-making capacity near Pittsburgh was shuttered. Sprawling facilities running along the Monongahela and Ohio rivers toppled like ten pins: the Pittsburgh Steel plant in Monessen, U.S. Steel facilities in McKeesport, Duquesne and Homestead, J & L’s works in Pittsburgh and Aliquippa. Who is to blame for this tragedy? Everybody and nobody. The demise of the steel industry in Pittsburgh played out with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy. Our loss of jobs was a body blow such as no major American city had ever received, and worse was to come. For a while, we consoled ourselves with the fact that Pittsburgh was the third-largest corporate headquarters city in the country. The brawn may have gone elsewhere, but the company brains remained in Pittsburgh. Sadly, though, more than 75 percent of our major corporations in 1970 are no longer here today. It’s easier to list those that are still here: PNC, U.S. Steel, Allegheny Technologies, H.J. Heinz, PPG and Mine Safety. We also have two Westinghouse spinoffs: Wesco and Westinghouse Nuclear, and two new arrivals headquartered here—Federated and Dick’s. It’s a short list.

A new day

Now, we live in a different Pittsburgh, with a cleaner and more beautiful environment. The region is a tourist destination. And our economy is more balanced than ever before. We can no longer be called a company town. Numerous opportunities in venture-backed start-ups and growing small businesses often are more appealing than a slow rise up the escalator of corporate hierarchy.

Three strong bell cows are leading us toward a knowledge-based future: Carnegie Mellon University—the leading computer science university in the world; the University of Pittsburgh—with broad-based strength capped by the health sciences and a school of medicine ranking sixth in NIH funding; and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, now the largest academic medical center in the nation with $7 billion in revenues and over 50,000 employees.

Like two-headed Janus, we may look forward to a promising future and, with great pride and a little nostalgia, look back to a time long ago when Pittsburgh forged the industrial might that made America the greatest nation in the world.