You could easily miss the Sharpsburg Community Library, even at its Main Street location next to the post office. This is not a Beaux Arts gem of the Carnegie system. Rather, it is 1,300 square feet in a one-story concrete-block former Indian restaurant. The little facility is well used and beloved, but we are lucky to have it at all. Before opening in the current location in 2008, the library functions survived for a few months as only a bookmobile. Now though, construction is set to begin on an addition that will nearly triple the facility’s space in a bold and contemporary structure by Arthur Lubetz of Front Studio Architects.

The transformation might just as easily have been more modest, explains Stephanie Flom. She was until early 2014 executive director of both the Boyd Community Center and the Cooper Siegel Library in Fox Chapel, the latter of which is the administrative custodian of the Sharpsburg Community Library, in partnership with the borough council. The original aspiration was simply to expand the community gardens in the back of the building. Flom recalls that state Sen. Jim Ferlo, a longtime supporter of new and expanded library facilities in his district, encouraged her to solicit designs and drawings for a substantial library addition, even as just a future projection.

Among architects expressing interest was Arthur Lubetz, who has practiced architecture in Pittsburgh for over 40 years and recently merged with Front Studio, a Manhattan-based firm founded by former students of his from Carnegie Mellon University with similarly adventurous design sensibilities.

Lubetz the teacher is also a librarian of sorts, whose expansive personal collection is numbered and cataloged. He is generally eager to philosophize on the relationship of architecture to books, libraries and a broader intellectual life: “Architecture isn’t just about architecture. It’s about philosophy, sociology, emotion, and art.” Some might construe this outlook as a sign of academic impracticality, especially when he produces designs that are rife with arhythmic angles, bright colors, and unexpected raw materials, except that such an approach has led to substantial success with particular relevance in, among other projects, the Squirrel Hill branch of the Carnegie Library.

That building, a renovation of a 1960s structure over a parking garage, uses an angled, glass-enclosed staircase protruding over the sidewalk and a tall, voluminous copper roof above the reading room for artistic adventurousness that enhances the indoor quiet of that particular space. Yet, these same elements make the building a unifying community space well-suited to reading, research, computer use and community activities, even as its children’s space is popular and active.

The Sharpsburg Community Library expansion promises similar results. “It’s very exciting that our little library could have this level of artisanship,” says Flom.

The design develops from a careful assessment of site and function. Where a previous plan simply expanded the library to the rear of its site, away from the street, Lubetz places a new community and program room along Main Street. That reorients what is effectively the library’s face toward the thoroughfare with the use of storefront-like glass. “It will give us program space to do a number of things that we couldn’t before,” says assistant librarian Jamie Cozza. It will also demonstrate to passersby that people are the library’s most important contents.

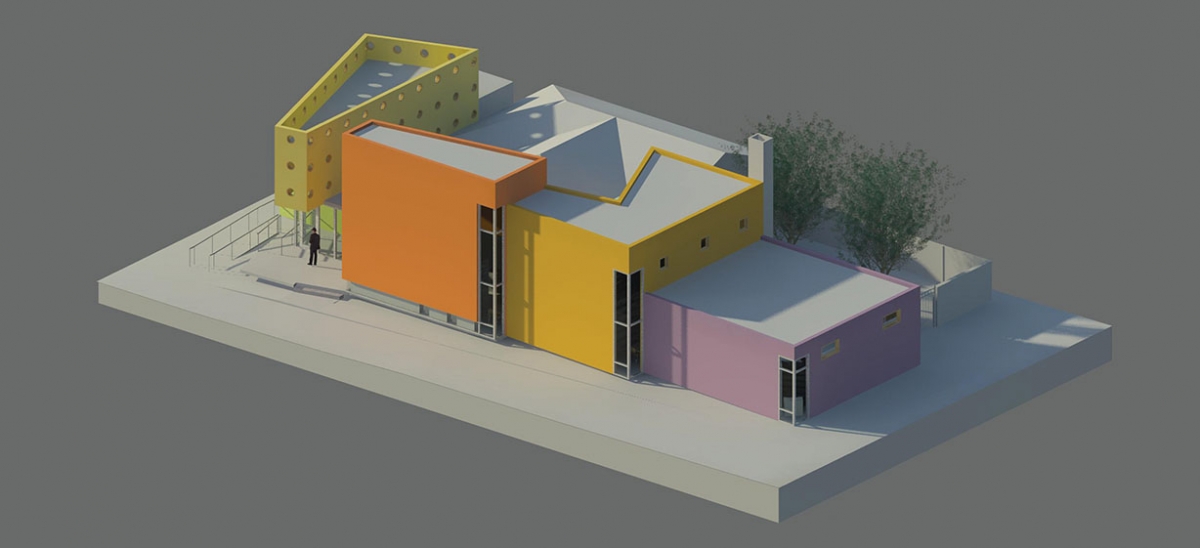

A tall, red slab marks the entry with the information desk, and it’s where the book stacks begin. More stacks and reading areas are in the adjacent mustard-colored box. The dedicated children’s area is in the violet-colored wing in the back, with its sheltering low roofline. The existing building, almost completely surrounded by new construction, will remain in use for study carrels and a laptop bar.

Architecture of this kind, Lubetz asserts, “engages people’s bodies and their minds and their imaginations.” It’s well suited to the intellectual stimulation of reading.

Ferlo allows that “there was a little controversy early on about what [Sharpsburg] Council thought was too colorful and bright,” but subsequent meetings have put that to rest. How do the library’s users like the model of the expansion that’s been on display? Cozza replies emphatically, “Oh, they like it; they’re excited.”

Part of the promise of Lubetz’s design is that it can appeal to different perspectives. Many people like it because it is childlike, with its many colors. The fragmented forms appear as building blocks. In another way, it is an effective metaphor for the experience of the library as a place where a community of people assembles for a range of activities, all of which may be different, but which nonetheless contribute to a dynamic whole.

Stephanie Flom is excited about the building now under construction in all of its shapes and capacities: “What started as a dream on the back burner has come to fruition.” Indeed, as much as the bright colors and angular geometries are new to the library and to Sharpsburg more broadly, they are less a sign of the transformation of the library than they are a more vivid indication of what it has been developing steadily into over the last few years.