The Great Banishment of 1923

Robert Young was one of the bad characters in Rosedale, a black neighborhood of Johnstown, after he arrived in 1923. Rumors swirled that he had committed murder in his native state of Alabama. And he had been having troubles with his significant other, Rose Young, since they arrived for him to work in the mills in the city. Robert had seen her run around with other men.

One night in late August of that year after the couple argued, he went to nearby Franklin Borough for drugs and moonshine. When he rode back to Rosedale in his buddy’s car, the driver and he got into an argument and they hit a telephone pole. A policeman approached. Young pulled a revolver and shot the officer, who stumbled back, and began firing back. Johnstown Police were dispatched to the scene.

Young went looking for Rose and broke into a neighbor’s house trying to find her. Eventually he got into another shootout with police, wounding and eventually killing four of them. The town was on edge, and much of the hostility was directed toward the killer’s race.

The event triggered one of the greatest racial injustices in American history, and it happened 70 miles from Pittsburgh.

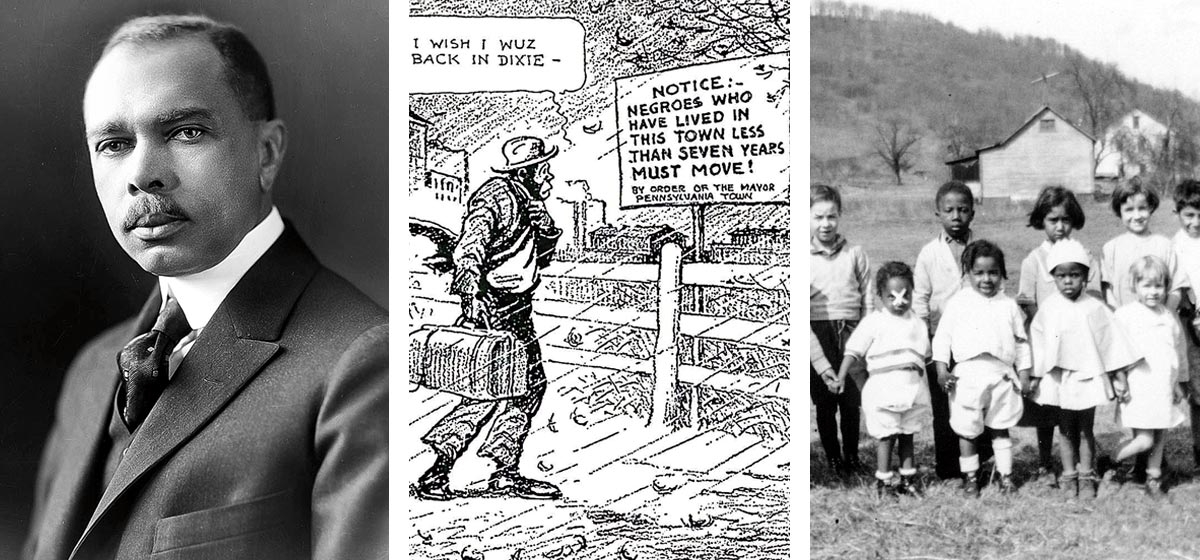

For the previous seven years, tens of thousands of African-Americans from the South came to western Pennsylvania as part of the Great Migration, a demographic shift of black Southerners to Northern industrial centers. Steel mills and other industries sent recruiters to lure Southern black workers north. In Johnstown, the chief recruiter was Bethlehem Steel.

The migrating black and Mexican workers often encountered racism and persecution from whites who feared the new arrivals threatened their jobs and would bring crime. Johnstown newspapers often highlighted the race of black and Mexican criminals when reporting on murders, thefts and other felonies. Suspicion and fear of the newcomers grew.

“They were surprised by the way they were treated,” said Ralph Proctor, who teaches African-American history at the Community College of Allegheny County. “They had been told that if you got north that racism wouldn’t exist. But they found out it existed strongly. It was a little more subtle than the South, but it was just as bad. The South had Jim Crow laws, and the North had Jim Crow customs that operated the same way.”

In Johnstown, they primarily settled in Rosedale, essentially a work camp set up three miles north of the business district. Living conditions shocked visitors.

“I have visited all types and kinds of communities in which Negroes live in all parts of the United States,” said Howard University professor Dean Kelly Miller in 1923. “I have seen them in alleys and shade places; I have witnessed their poverty and distress in city and country. But I can truthfully say that it has never been my good fortune or misfortune to look upon such pitiable conditions as prevailed in Johnstown.”

Crime was rampant in Rosedale, along with alcohol and drugs. Newspaper reports described gangs of men threatening to assault women. The larger, productive and law-abiding portion of the population that went to church regularly got lumped in with the criminal element by white Johnstown.

After Robert Young was killed, and after news reached Johnstown that he killed a few officers, much of the public believed a race riot was at hand. Whites congregated around city hall threatening to burn Rosedale to avenge the officers.

At that time, Joseph Cauffiel was both Johnstown mayor and primary magistrate, and he had a reputation for being hard on blacks and Mexicans, once ordering a courtroom officer to shoot blanks at a black defendant. Aggravating the situation was that Cauffiel faced a fall primary election, and he trailed his opponents. He needed to galvanize voters. One of the more powerful constituencies in Johnstown was the Ku Klux Klan, which had grown faster in that part of the state than in any other during its national revival. The Klan controlled thousands of Johnstown votes, and Cauffiel saw opportunity following the shooting of the four officers.

Cauffiel had a testy relationship with local newspapers. The Johnstown Tribune, a Republican newspaper, had issues with the mayor following his physical altercation with its editor, who was upset that one of his reporters was detained by police for his coverage of Cauffiel’s courtroom. The rival paper, the Johnstown Democrat, had opposed most of Cauffiel’s policies. The Democrat still published news of him, while the Tribune was reluctant to give him press for fear of increasing his reelection chances.

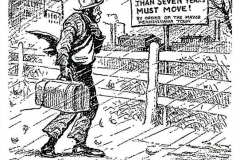

On Sept. 6, 1923, Cauffiel called the Johnstown Democrat’s offices and asked that they send a reporter to his office. Ray Krimm got the assignment. Cauffiel told Krimm that black people living in Johnstown were prohibited from holding public gatherings and would not be allowed to assemble except for church. He also said he was ordering all blacks and Mexicans who had lived there less than seven years to leave town immediately.

“We cannot tell how many of these Negroes who have been shipped in here have criminal records until we get them in some escapade or act of lawlessness and then write back to their hometown to secure their records,” Cauffiel said. “Such procedure has cost the city of Johnstown the lives of two of her most faithful police officers and has placed four others in local hospitals, two of the wounded yet being in serious conditions, with their prospects of living yet undetermined.”

In large, bold and italicized lettering, the Sept. 7, 1924 Johnstown Democrat headline blared: “MAYOR CAUFFIEL SAYS UNDESIRABLE NEGROES MUST QUIT JOHNSTOWN.”

The sub-headline read, “Says only those who have been here seven years will be permitted to remain and that future importations will be barred—admits, however, that some new arrivals make good citizens and speaks highly of older residents of that race.”

The next day the Ku Klux Klan burned 14 crosses around the hills of Johnstown. From every hill and mountainside, on all sides of the city, the crosses blazed forth. As the demonstration was at its height, the Johnstown Democrat received a telephone call from a man claiming to be a Klansman.

“We want you to understand that our demonstration tonight is not directed toward the law-abiding Negroes of Johnstown,” he said. “We are after that dirty crew that has been sent into Johnstown—those questionable characters gathered from questionable neighborhoods in other cities and dumped upon Johnstown to stage their drunken revels, their shooting sprees and their murderous designs. It is to that class of the Negro race that we are directing our forces. They may take our demonstration tonight as a warning. They are not wanted in Johnstown. Tell them to clear out.”

According to later reports, more than 2,000 black people walked out of the city, penniless and scared. Some were forced out at gunpoint, as an NAACP investigator later found out.

Within Johnstown’s media, each newspaper received the news differently. At the Tribune, it was largely ignored. At the Johnstown Democrat, owner Warren Worth Bailey was appalled and alerted the American Civil Liberties Union.

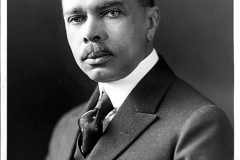

But it wasn’t until black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier caught wind of it that the outrage escalated. The Courier was owned by Robert L. Vann, a thin, well-dressed 44-year-old who worked long hours, often without stopping for dinner. Vann would make the Courier a newspaper of national repute and consequence, and today the Robert L. Vann Awards for journalistic excellence are given in his honor.

When the Johnstown news reached his ears, Vann and the Courier staff swung into action. Reporters spread out. Editorials condemned Cauffiel. And national attention began to focus on Johnstown.

Other black newspapers—the Chicago Defender and Baltimore Afro-American—followed suit. White newspapers picked up the story. The scandal reached the desk of James Weldon Johnson, executive secretary of the NAACP, little more than a decade old but becoming the nation’s preeminent champion of civil rights for its ability to galvanize and organize black voters and communities.

Johnson telegrammed Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot, who, along with his wife Cornelia, was known as a supporter of the African-American community. But Pinchot had also been a staunch Prohibitionist, and thus supported Cauffiel’s frequent crusades against bootleggers and criminals. He counted Cauffiel as a friend.

Pinchot launched an investigation and the state attorney general sent a deputy to Johnstown. Across the nation, journalists decried the Johnstown decree and Cauffiel was portrayed as a despot and tyrant.

Southern newspapers took the incident as an opportunity to try to lure blacks back to the Cotton Belt. The South had lost huge numbers of laborers to the North and its economy had suffered. Southern papers capitalized on incidents of Northern racism, saying life was better for blacks in the South. Northern black papers countered, claiming hypocrisy and pointing out the South’s far worse Jim Crow culture.

The attention wearied Johnstown voters. They had taken pride in being known as the friendly city. And on Sept. 19, they voted Cauffiel out of office. Cauffiel later served another term as mayor before being imprisoned for extortion, perjury and other misdemeanors. When he died, Johnstown City Hall was draped in mourning for 30 days as a tribute to his memory.

Racism and bigotry peaked in the early 1920s in western Pennsylvania. But in the decade following the Rosedale exodus, Klan membership in Cambria County, where Johnstown is located, and elsewhere declined. It peaked shortly after 1923 but the secret order had held ostentatious cross burnings and mass gatherings, including on “Klan Day,” which attracted 14,000 people from all around western Pennsylvania. At some initiations, 4,000 people from Cambria and neighboring Somerset and Westmoreland counties came.

Eventually the Klan lost its mass appeal. Imprisoned Klansmen were not seen as martyrs anymore, and the group’s violent reputation hurt its ability to recruit. By 1929, the Johnstown Klavern, the self-given name of the local Klan chapter, was all but gone.

This story is part of the Rosedale Oral History Project, which tells the stories of 2,000 African-Americans who were forced out of Johnstown in 1923. A forthcoming book will be released about the topic.