You’re not the boss of me

The sweatshirt is off-pink. It has shoulder pads.

“The shoulder pads make it slimming,” my mother says. “And it’s not pink. It’s burnt salmon.”

We sit on my mother’s bed, two co-eds at a sleepover. My mother is just back from a vacation she wasn’t well enough to go on. She’s still dressed for the boardwalk—velour track suit, running shoes, the good necklace she bought on a trip we took to Greece years ago.

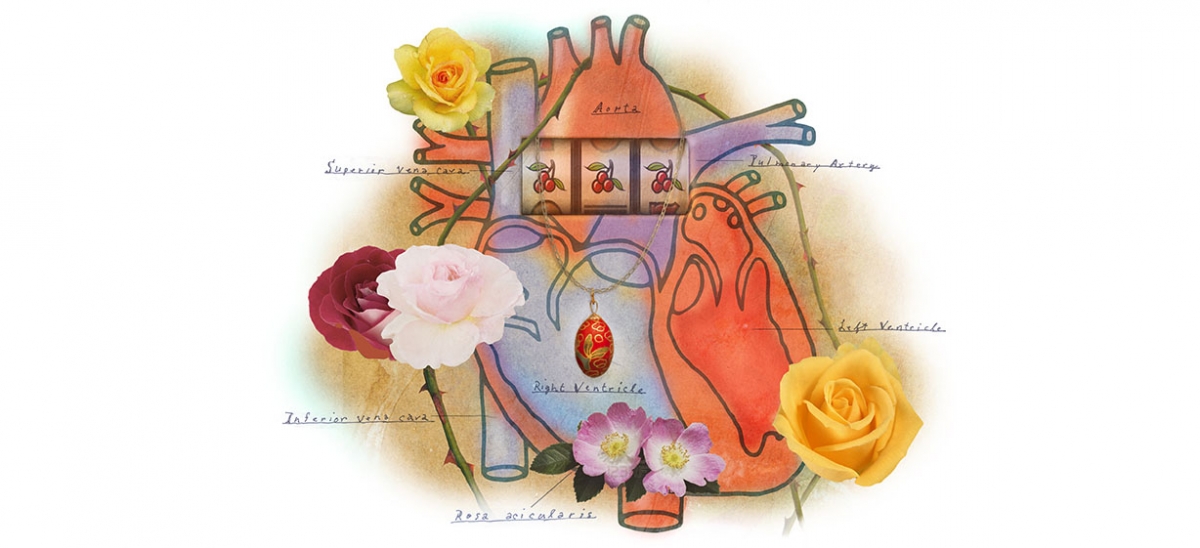

The necklace is a pendant, a tiny red-and-gold cloisonné egg from a gift shop in Santorini. The shop specialized in egg necklaces and sea sponges and was perched at the top of a mountain. We climbed dozens of steps to get there, stopping and starting all the way for my mother to catch her breath.

“Wait at the bottom. I’ll go,” I’d said, but my mother, who didn’t have much good jewelry, who’d set her heart on this egg because her friend Dot had smugly come back from Europe with one and my mother was tired of Dot thinking she was better than everyone, had said, “I don’t trust your taste. I want to pick it myself.”

Now the necklace settles into the tiny indentation in her throat, a nest. My mother looks thin, but happy. She puts the sweatshirt up to my shoulders, measuring. I take it from her and hold it at arm’s length.

“Thanks, Mom, it’s perfect,” I say.

It takes a while to realize where I’ve seen this shade before. It’s the color of the sawdust janitors in elementary schools use when someone pukes in the halls.

I start to fold the sweatshirt back into a plastic bag labeled “Slots A Lot.”

“Aren’t you going to try it on?” my mother asks. “I got it in a large.”

I do not wear pastels. My mother knows this. Black, of course. Brown, fine. The occasional gray. It’s been almost 20 years since I’ve considered anything pink, let alone burnt salmon. I’m a size medium. I’m sensitive about this. My mother knows that, too. Shoulder pads went out in the ’80s. Shoulder pads make ordinary women look like Russian mobsters. I’m not athletic. I do not own sweatshirts, not even a hoodie.

I take the shirt back out of the bag, unfold it and slide it over my head. The shirt smells flammable. It’s probably the puffy paint. “Atlantic City is for Lovers” is scrawled across the chest. There is a glittered puffy-paint heart on one sleeve.

“Get it?” my mother says. “You wear your heart on your sleeve!”

She says, “Now isn’t that clever!”

She says, “I knew it. Any smaller would have been too tight.”

She says, “A little color perks you right up. Every day isn’t a funeral, you know.”

Along with the sweatshirt, she’s brought me a lucky number 7 keychain and a baggie of toiletries she swiped from her hotel. “I asked for extras,” she says. “Smell the shampoo. It’s cherry. Lucky cherries. Everything’s lucky out there.”

Maybe it has something to do with divine intervention. Maybe the Greek egg necklace does what the Santorini gift shop owner promised. Maybe it wards off evil and brings good fortune and second chances. Whatever it is, my mother had been lucky out there. For the first time ever, she hit—$250 in nickels on a Wild Cherry slot machine.

“The machine was spitting it out like popcorn,” she says. “All the lights were flashing, a siren was going off. I thought I was going to have a heart attack.” My mother’s heart is exactly the problem.

“Not funny,” I say, and rub the puffy paint.

“Figure of speech,” she says. “You worry too much.”

Later, Aunt Thelma comes over and rats her out.

“She didn’t feel good,” Thelma says. She wears a sweatshirt exactly like mine, same puffy heart on the same sleeve, but in blue. Blue, my mother says, is Thelma’s color. It’s my mother’s color, too. In her closet, there’s a spectrum, every shade of sky.

Right now, my mother is in the kitchen, puttering with the teapot. Thelma and I are in the living room. Thelma’s keeping her voice down. She crouches to match her voice and I have to stoop to hear her.

I think my mother and her sister imitate old movie stars. Or maybe it’s just people of their generation have a more over-the-top way of doing things. “We lived through the Depression,” my mother likes to say, as if this explains everything.

“She stayed inside and slept a lot,” Thelma says. She looks like a turtle, her chin covertly tucked down and nearly lost inside her sweatshirt. “She was too tired to walk on the beach.”

When my mother comes in with cups of tea, Thelma sits up straight and changes the subject. “The crab legs,” she says. “They were all you can eat. Really fresh, big piles of them, and so sweet they melted like butter.”

Butter is not on my mother’s heart-approved foods list. Butter is off limits. I keep my mother’s refrigerator stocked with Smart Balance. I keep a gallon of olive oil in the garage. I am so afraid of losing my mother the way I’ve already lost my father. He’s been dead less than a year now.

“First one goes, then the other,” the funeral director had said.

“Just like butter,” my mother says about the crab legs, and she’s looking at me.

You know I hate the beach,” my mother says. “Stop treating me like a child.”

“Stop spying on me,” she says. “I deserve a little vacation.”

“What did you think was going to happen?” she says.

She says, “It wasn’t butter. It was margarine.”

She says, without a bit of irony, “You’re not the boss of me.”

And this is when she suggests I stop staying at her house every night.

I am my mother’s caregiver. This is what I tell myself and anyone who asks. These days, this is the only identity I know. My mother had been very sick. Now she is less so. I gave up my job in New York. I gave up my apartment there. I moved back home to Pittsburgh to take care of a mother who no longer needs that kind of care. I’m not sure where this leaves me.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” I say. “You can’t be here alone.”

“I most certainly can be,” she says. “This is my house.” Then, more gently, “You’ll be here if I need you. I know that.”

I follow her to the living room closet, where she shows me the box. For some time, she’s been packing it. The box is full of supplies for the apartment I rented a few miles away. I thought of the apartment as a life raft, as a just-in-case thing I’d probably never really use.

I look down at the box, my mother’s parting gift.

“You’ve been planning this?” I say.

She says, “There was a special on paper towels. Buy one, get one.”

When I unpack the box back at my mostly empty apartment, I will find the paper towels. I will find rolls of toilet paper, a set of tea mugs, a box of sugar wafers, a tin of tea bags, some washcloths and a set of dishrags with ducks on them.

“You want me to go now?” I say to my mother as she motions for me to pick up the box and opens the door.

“It’s time we get on with things,” she says.

“Not right this second,” I say. “We need to see what the doctor says about this, if you’re ready.”

She says, “That doctor,” and sighs.

She says, “No time like the present,” and waves me to the door.

The air outside smells sweet, my mother’s roses. She’s planted them alongside the house. She and my father used to fight over these roses. He hated to mow around them. “Too much trouble,” he’d say, and she’d say, “Well, so are you.”

Once, on accident I think, my father mowed one over. My mother never let him forget this. “You kill everything good,” she said to him. “You kill anything that makes me happy.”

My mother leaves the tags on all the rose bushes so she can remember the names. Pink Maiden. Lady’s Blush. Sunny Knock Out. To replace the bush he cut down, my father mail-ordered a rose bush named after my mother. The Alberta rose is red and open, like a poppy, with a tiny sun burning at the center. “It doesn’t look like much of a rose,” my mother said, but she was smiling, happy as always to get her way.

There’s nothing else to do, so I carry the box out to my car, past the roses, past the hummingbird feeder my mother keeps full of red sugar water. She comes out to the edge of the porch, but that’s as far as she’ll go. She lets me kiss her cheek but doesn’t kiss back. She makes a dramatic sweep with her arm. “Go on,” she says. “I’ll call you later.”

The egg necklace bobs against her neck, a tiny heart.

Back on Santorini, in that shop on top of the mountain, my mother flirted with the owner. He looked like a fisherman in his little cap. He could have been 60. He could have been 80. They looked into each other’s eyes as they haggled over prices. She told him she liked his hat. He complimented her sweater, her good taste.

“Red,” he said as she looked over the necklaces, “is the best choice. Though I think you know this.”

He took my mother’s hand, cupped it between his own, and told her a story I think he told often as part of his sales pitch. The story was one I’d never heard—about Mary Magdalene. No one believed her when she told them about Jesus’ resurrection. They thought she was mad, a mad and wanton woman. And so she did something odd. She started to carry an egg with her wherever she went.

“She’d tell people, ‘I know, I know. The idea that someone could rise from the dead is crazy,'” the shopkeeper said, ” ‘as crazy as this egg turning red in my hand.'”

Then the shop owner opened his hands and set my mother’s free like a small bird.

“And the egg,” he said, “turned red in her hand.”

This symbol of resurrection, of faith, a blood spot at my mother’s throat.

On the porch, she puts her hands on her hips and anchors down.

She says, “You have your life. I have mine.”

“But I don’t,” I say, and can’t tell whether she hears me or not.