It’s early, the sun is just peeking up over those western Pennsylvania hills, and it’s cold and bleak as he pulls into the brightly lit service station-cum-convenience store to fill up the pressed-steel canyon that is the fuel tank of the company-owned Cummins 3500 pickup he’s driving.

There’s nothing in the world that Shawn Clark wants more than a reassuringly hot and reliably bland cup of Pennsylvania gas station coffee.

It won’t be the last cup of the day, but it’ll warm him up and get his blood flowing so he can begin his 15-hour day at the job. Seven hours on, seven hours off. It’ll be another two weeks before Shawn gets another day off. But he doesn’t mind. It’s not like he’s got a girlfriend or a wife or anything. Besides, the work is interesting, most of the time. And the money’s good—really good. Last year he grossed $80,000—not too bad for the depths of a recession, and if things keep going the way they’re going, he could be “on the page” for $100,000 this year. Clark can certainly afford to buy himself a cup of coffee. He can even afford to buy a couple of cups for his guys. His guys. Even he sees the irony in that. He’s only 21, and yet depending on the job, he’s supervising any- where from two to 15 men, making sure they’re safe and that they know how to handle the equipment that man- ages the flow back, the hundreds of thousands of gallons of chemically treated water that rushes back out of a gas well after hydrofracking. It’s a big job. And an important one. It’s not just his youth that makes him a bit of an anomaly in the growing Marcellus gas fields of Pennsylvania. It’s the fact that he’s homegrown, a western Pennsylvania boy, born and bred. In most parts of the Marcellus, the job he’s doing, and the jobs his boys are doing, would be done by Texans, or Oklahomans or Arkansans specially imported into the state because, after years of falling oil and gas prices, Pennsylvania had all but stopped training people to do this kind of work. Those skills had been virtually lost here. His own company, Eastern Reservoir Services, a division of Universal Well Services out of Meadville, was one the few local companies that hadn’t lost the skills; the company had seen fit to train him and his guys just as the Marcellus boom was beginning. Now he is a supervisor.

That would have made his old man proud, Shawn thinks. Kim Clark had been in the business, too. He didn’t work on a rig, or at the well head. He was a salesman, selling drill bits and other equipment, and back when Shawn was a child, the old man spent most of his life on the road. The only way Shawn could spend any time with him was if he went along with him on business trips, and he often did—a baby, really, curled up in the back of his father’s Ford pickup. The old man put a television back there to keep Shawn amused as they rattled along gravel service roads to far-flung drill pads all over the east, from Pennsylvania all the way up to Nova Scotia. Shawn was only 7 when his father died. He was killed in a car crash. That was back in the early ’90s, right about the same time that the oil and gas industry, and the jobs and training that came with it, were being choked off. Now it was all coming back, the industry, the jobs. Right now, most of those jobs were being filled by out of state workers, but maybe Shawn was the first wave of what could be, if the state and the local school districts and the industry itself could gear up and provide the training that would be need- ed to fill those jobs with Pennsylvanians. The way Shawn sees it, his old man might not have been too pleased with the truck he was driving—he was a Ford man all his life—but as for the rest of it, he would have been pleased. “I’m following his path.”

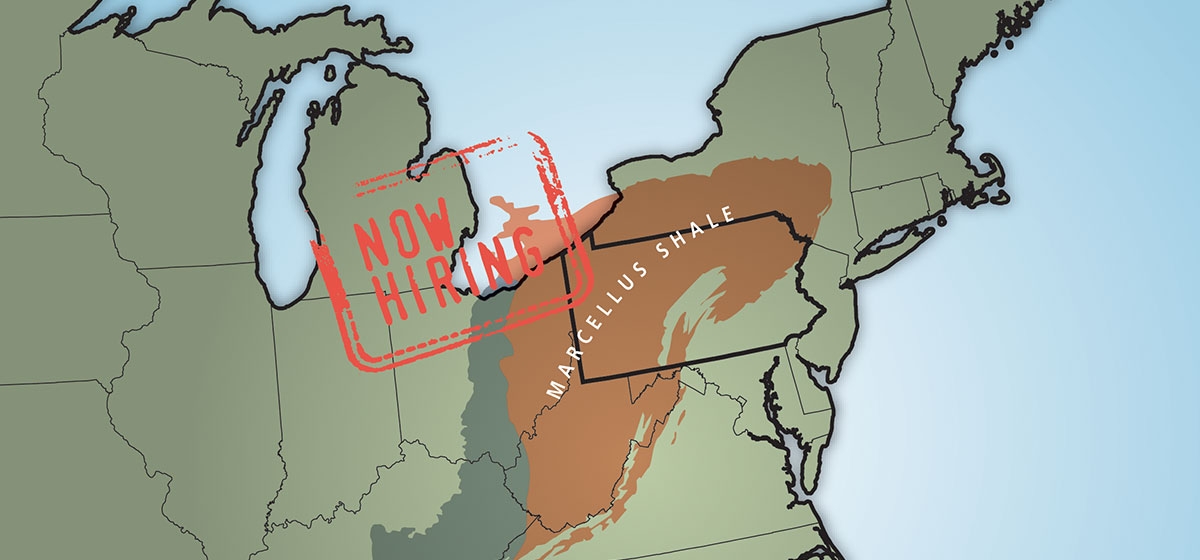

It’s been slightly more than five years since the first wells were drilled into the Marcellus shale, tapping into a vast and lucrative energy resource, a resource estimated to contain nearly 500 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas; enough to fuel every gas-burning device in the United States for a generation; a field rich enough to earn the drillers, the men and women who work for them, and even the state itself, billions upon billions of dollars over the next several decades. Over those five years, hundreds of thousands of words have been written about the potential economic benefits the state may reap from the development of the Marcellus as all that money rushes out of the tens of thou- sands of wells expected to be drilled. Each well requires 415 workers from 150 different kinds of companies to release and harness the fuel. But in all of those stories, at least so far, there has been comparatively little discussion about the significant hurdles faced by the state’s educational infrastructure as it struggles to find a way to make sure that Pennsylvanians have a fighting chance of getting those jobs.

It’s an issue that’s been overshadowed in large part by the environmental questions that surround the development. It’s been eclipsed in the press, too, by the debate about how the Marcellus Play, as it’s called, fits into the nation’s energy future. But it’s one of the most critical unresolved issues involving the burgeoning gas fields here: how can a state that overlays 60 per- cent of the Marcellus and that was, in many respects, caught flat-footed by the Marcellus gas boom, best rebuild an educational system that can maximize the economic benefits of the Marcellus in Pennsylvania?

“We are behind the eight ball,” says Stephen Rhoads, until recently the president of the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Association, now director of external affairs for East Resources, a drilling company that controls some 1.5 million acres of Marcellus land. “There was a deep depression in the oil and gas industry in Pennsylvania in the ’80s and ’90s, and we lost a generation or two of labor… and now we don’t have the educational infrastructure, from high school to community college to baccalaureate programs.” Rhoads is not alone in recognizing the urgency of developing an educational system that can provide a skilled and ready work force for the burgeoning Marcellus Play. According to a 2009 study by Penn State’s Penn College of Technology in Williamsport, in the northern and central parts of Pennsylvania alone, the industry will require more than 8,000 new workers by 2013 if development continues at its current pace. Only a comparative handful of those jobs will be in those tweedy, khaki-collared professions like engineering and geology, says Tim Kelsey, a rural economist at Penn State who has been closely monitoring the economic impact of the Marcellus since 2005. The vast majority of those jobs—fully three-quarters of them— will be jobs that don’t require a college education. The bulk of the job creation, he says, has been and will continue to be entry-level jobs as laborers and roustabouts, positions that require a modicum of training, to positions as roughnecks working on the rigs, which require additional training, as well as ancillary jobs such as welders and commercial drivers skilled in off-road work.

And therein, he says, lies the rub. Two decades ago, Pennsylvania had a fairly formidable network of schools and programs capable of training workers at all levels of the industry. But when the market for oil and gas collapsed, so too did all but the very top of that infrastructure. While the state’s major universities—Penn State, Carnegie Mellon, the University of Pittsburgh—continued to churn out world-class students in petroleum engineering, geology and related sciences, students who went on to work in high-level positions at virtually all the major oil and gas companies in the nation, those students effectively became an export. Their skills were largely applied from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of Oman—everywhere, it seemed, except for the state of Pennsylvania. In the meantime, the pro- grams that could train the vast majority of needed local workers atrophied and died. And the industry must import out-of-state workers at a premium.

That was what happened at the University of Pittsburgh’s exemplary two-year petroleum technology program offered at its Bradford campus in the heart of the state’s traditional oil and gas region. The program, which graduated its first class in 1970, produced a steady stream of qualified gas field workers for nearly 19 years. They weren’t masters of gas field technology when they graduated with their associate degrees; it still took three months of on-the-job training to get up to speed, but they had the skills to get their foot in the door, said Dr. Assad Panah, the program’s director. They were trained technicians, and they had the skills to begin work on drill rigs, and on the collection and transportation of gas; they had basic knowledge of geology and the geographic skills to help map gas fields. They even had the basic skills to do the kind of environmental monitoring needed not just by the drillers, but by agencies such as the state Department of Environmental Protection and the federal Environmental Protection Agency, charged with overseeing those industries. It was a successful program, Panah says, and its graduates found jobs with all of the major producers.

But then, when oil dipped to $9 a barrel in 1988, triggering an industrywide recession and sparking layoffs, the pro- gram closed its doors. “We were not training. Nobody else was training,” he said, and the university began actively trying to steer students away from an interest in petroleum technology. They had good reason. Their graduates, they learned, had not only often been “fired by oil companies because there wasn’t work to do, they left the business for a different kind of field. So all those we had trained, most of them left the oil industry and went to other places.”

By 2006, just as the Marcellus boom was beginning, Pennsylvania’s once skilled oil and gas workforce had been decimated. Most of those who had managed to hold onto their jobs during the oil and gas recession were now older, in their late 40s, 50s and even 60s, and were moving toward retirement. There was no one to replace them. And neither the state Department of Labor nor the Department of Education had any comprehensive plan to fill that gap. But Panah did. Recognizing that the Marcellus boom offered great potential, but also seeing advancements in things such as hydrofracking technology that had made the boom possible, Panah and the university decided to retool and reopen their doors. There are currently 27 students enrolled in the program. That may not seem like much, Panah concedes, but considering the fact that four years ago the number was zero, it’s a start.

To be sure, the University of Pittsburgh’s Bradford program is not the only one planning to augment the state’s potential Marcellus work force. Right now leaders from several of the major gas companies are exploring the idea of developing a Marcellus Institute, said Dr. Robert Watson, a lifelong gas and oil man who recently retired as a professor at Penn State, where he had been studying the development of the Marcellus. It would, Watson said, follow the University of Pittsburgh’s lead and would encompass “not only Penn State… but most of the schools west of Penn State in places like Pitt and West Virginia, and for that matter, Carnegie Mellon, which is a private university.”

And there are already several programs up and running across the state.

Penn College of Technology, for example, has been working with modest sup- port from several drilling companies as well as support from the Department of Labor’s Workforce Investment Program and Careerlinks to create a program called “Fit-4-Natural Gas”; a three-week, 12- hour-a-day program to train workers for entry-level and roustabout jobs in the gas field. In the first class, there were 15 students ranging from their early 20s to mid- 40s, many of them workers who had been displaced from other industries by the recession. They graduated in July 2009, and program director Tracy Brundage said the school does not know yet how many have found jobs in the gas industry.

Closer to home, at the Western Area Career and Technology Center in Houston, Pa., Dr. Joe Iannetti is running a program with substantial material support from drillers, among them Range Resources. So far it has trained about 150 people, both high-school-aged students and displaced adult workers, in the basics of gas field work, as well as in specialties such as welding, electrical work and commercial driving—skills Iannetti believes can help land them jobs in the industry. But not overnight. It takes three years for the high-school-age kids to complete their course of study and two years for the adults.

As promising as the programs at Bradford and Houston are, there are a lot of jobs in the gas fields of the Marcellus that can’t wait two or three years to be filled, said Dennis Dull, vice president of operations for the Institute of High Priority Occupations, a consulting firm that provides curriculum and training for career training centers—public schools that used to be known as vo-techs—in Washington and Fayette counties and in the city of Pittsburgh. And there are also a lot of local guys who, having been hammered by two years of recession, can’t afford to wait two or three years to get a paycheck.

That’s why the institute, with the support of several of the major drilling and gas field service companies, including Universal, Red Oak and Patterson Drilling, and support from local school districts and politicians, has developed a six-week pro- gram designed to train students—teens and adults—for entry-level jobs in the drilling industry. The students, who must pass an exhaustive written exam to graduate, aren’t going to get rich overnight. But they can reasonably expect to find jobs, Dull said, noting that about 75 percent of those who’ve completed the program have. And they can expect to earn about $19 an hour, plus overtime.

Similar programs are expected to continue to evolve throughout the state as the development of the Marcellus expands and as more local authorities, regional Workforce Investment Boards, local school districts and community colleges discover the opportunities it offers. At least that’s what state officials from the Department of Education and the Department of Labor expect.

It is a reasonable expectation. After all, those are the agencies and authorities charged with making sure the education provided to Pennsylvanians will adequately prepare them for the opportunities that exist in the state, and which, if the prognostications about the Marcellus are correct, will be present here for generations. But those agencies are in large part publicly funded. Many of the major companies recognize that it is in their interest to develop the local workforce, and not just for its significant public relations benefit. It benefits them from a financial perspective, too—it costs a fortune to transport, feed and house an imported workforce. Many of these companies are supporting educational initiatives, but there is not yet a mechanism to guarantee that support will continue.

As Terry Ooms, executive director of the Urban Institute, a think tank funded by several northeastern Pennsylvania universities, put it, that concern may have to be addressed down the road. As the state develops a more comprehensive list of regulations governing the Marcellus, that will trigger fees and penalties for noncompliance, and no doubt a mechanism will develop to funnel some of that money into education. For now, however, the education itself is the priority. “We’ve always said that our economic development’s success is going to be based on our education or our educated work force, and so I think it’s incumbent upon the school districts to develop these programs and make them available to students if they believe that they’re in a core area where there’s going to be some critical mass of student involvement.”

There is, of course, another challenge. Even if the state’s educational infrastructure could provide enough desks and field trips, it is still an open question whether there are enough potential students to fill all of those spaces, and whether they can last long enough to fill the jobs and keep a big chunk of Pennsylvania’s gas money in Pennsylvania.

Working in a gas field is not like working in a factory or a warehouse or even a coal mine. It’s not just that the work is physically demanding and can be dangerous. It’s that the hours can be grueling. It’s not at all uncommon for gas field workers to work 15 or more hours a day for 14 or 15 days in a row before they get a break. As the educators who have been trying to bring the state’s work force up to speed can attest, that can winnow the field of prospective students pretty quickly. Tracy Bundrage saw that when Penn College offered its first information session last summer for its new oil and gas program. The information session had drawn about 100 prospective students. But after explaining what the job entailed and that even the classes would meet for 12 hours a day to acclimate the students to that kind of schedule, 85 of the would-be roustabouts decided against signing up for the program.

Maybe it does take a certain kind of person to work in the gas fields, to deal with the long hours, and the grueling grind of it all, said Shawn Clark. And maybe it helps if you were born to it, as he was. But he said that’s not necessary. In his view, all you really need is what he and his boys have in abundance, the willingness “to work… to show up… and… pass a drug test.”

Even with that last part, Shawn said, there are still a lot of guys from Pennsylvania who could do what he does and maybe even do it better than the imported Texans. “We’re gonna need people from Pennsylvania to get into this. I mean we hired some guys from Texas and Oklahoma, and they haven’t even worked out.”