Wild Bones

My daughter brings home bones

and piles them on the driveway: femur, rib, jawbone with a few flat teeth attached, dozens of thin arced parts.

—from “My Daughter Brings Home Bones” by Jennifer Richter

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”163″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

The American photographer Sally Mann, controversial in the 1990s for the photos she took of her naked children, has a fascination with death. As she describes in her superb book, “Hold Still,” she has documented death by photographing decaying human bodies in Sweden. When her beloved greyhound, Eva, died, Mann buried the body on her Virginia farm, let it decompose for a while, dug it up, and photographed the bones. She wrote: “I grew curious about what would finally become of that head I had stroked, oh, ten thousand times, those paws she had so delicately crossed as she lay by my desk, their rock-hard nails emerging from downy white hairs.”

Our dogs are buried on our Pennsylvania farm in graves covered in daffodils with locust crosses at the head, and I have no interest in digging up the bodies to see what has become of them. I prefer my memories. Unlike Mann, I have no obsession with corpses. I don’t like open caskets. I’m not a fan of stuffed animal trophies. I don’t care for bones in my salmon, or touching raw meat. But I do collect animal remains I find on our farm.

My husband uses deer bones to polish his riding boots, but otherwise I’d never contemplated what people did with wild animal parts. I can buy badger toes for $7.50, wild boar ribs for $10.40, a bat jaw pendant with amethyst for $45, or a coyote femur with an infection for $7.20. “Ethically sourced” bones can be purchased individually or by the pound, in “found condition,” weathered, sanitized, or boiled. Artists make bones into jewelry, macramé, sculpture, musical instruments, lamps, dreamcatchers, buttons, and knife handles. Feathers, claws, fangs and bones are used for witchcraft, movie props, costumes, and children’s “dinosaur” birthday parties. And, in comparison to the true bone hunters, my collection is downright mundane.

Still, I like to study bones up close and identify them. It’s the same impulse as when I collect seashells. When my daughter was young, she and I spent hours combing Florida beaches looking for seashells. Back at home, we’d get out the field guides, identify the shells, put them into shadow boxes, and label them. Around the same time, a friend showed us seashells her grandmother had collected years before, and there were many my daughter and I had never seen. So I believe seashells and animal remains are artifacts of some historical significance—a record of the creatures that swim in our seas and roam our forests at a particular moment in history.

While my collection may seem to me somewhat commonplace now, who knows how long the same creatures will stay in the same locations? W. David Walter, Ph.D., an adjunct assistant professor of wildlife ecology at Penn State, said white-tailed deer are here to stay—they’re resilient and their populations large in Pennsylvania. “I don’t see much taking them out anytime soon,” he said. But moose are disappearing in New Hampshire, and, according to Audubon, 314 bird species are threatened by climate change. That includes the wild turkey, which forages in our oak forests and is predicted to lose 87 percent of its winter range by 2080 (turkey are not currently in decline, according to Walter). In the eastern part of our state, the Delmarva fox squirrel is endangered, the bog turtle is threatened, and on our western PA farm, there’s hardly a bat in the evening sky. Bees, as everyone knows, are in a desperate decline. “Climate change won’t do many species any favors,” Walter said.

Throughout the 30 years I’ve lived on the farm, I’ve found animal remnants any curious six-year-old might: hawk feathers, cicada exoskeletons, luna moths, snake eggs, newts, hornet’s nests, and crayfish, to mention a few. I found a perfect specimen of a belted kingfisher, which had died by flying into the slats of an Adirondack chair, and once I dug up in my flower garden a fisher cat—I presume the dog had buried it there—but I gave those to Powdermill Nature Reserve. One night not long ago, trying to sleep on our sleeping porch, I was awakened by a bloodcurdling sound. Our neighbor heard it too, and rushed to the chicken coop to make sure the chickens were OK. But I wasn’t worried about the chickens. They weren’t sounding their familiar battle cry when danger is at hand, which our younger dog and I know well—she always runs out to protect them. At first, I thought the skirmish might be a fox fight, but that didn’t make sense because only one animal seemed to be screaming.

The creature turned out to be a mink, which in all these years I’d never seen on the farm. Twelve to 14 inches in length, with a long tail and a dark and lustrous pelt, the mink, though dead, had only a small cut on its back. It looked as if it was trying to escape whatever was attacking it—a great horned owl perhaps—by crawling under the stone wall near our pond. I left the carcass outdoors to allow Mother Nature to give it an initial clean, and kept the bones.

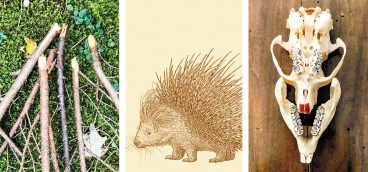

Deep into the woods and in our fields, I’ve found deer antlers, box turtle shells, raccoon skulls, and other body parts of deceased creatures. Here are photographs of some of them, and what else exists—or at least what I’ve found—circa 2018, in the wilds of western Pennsylvania.