Wild Apples

“Goddesses are fabled to have contended for it, dragons were set to watch it, and heroes were employed to pluck it. … Surely the apple is the noblest of fruits.” — Henry David Thoreau in “Wild Apples”

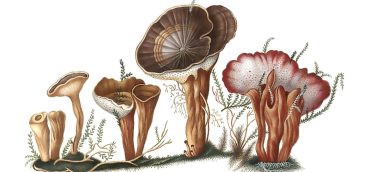

illustration: Stacy Innerst

April 24, 2025

A summer apple tree in the front yard is a wondrous thing.

I can sit on the front porch and watch apples fall to the ground, listen to the “plunk” as they hit the grass, and wildlife come right to me. A squirrel climbs the tree, plucks an apple from a branch and runs away with fruit in its mouth. Downy woodpeckers hang upside down on high branches to peck on the fruit. Young bucks with velvet antlers sneak across the lawn to eat apples and a groundhog waddles across the grass, stands on his hind legs, and nibbles. Bold is he in the middle of the day with me watching — and two groundhog-chasing dogs.

Yellow jackets and ants finish off the bruised and half-eaten fruit. I got a painful sting once that itched for days afterward, simply trying to collect some fruit to make applesauce for the humans who dwell here.

In spring, I can stand underneath the apple tree and listen to the bees as they feast on the pink blossoms.

Ours are old apple trees, on the farm when we moved here 36 years ago. The tree closest to the porch, the one I watch so closely, already had cement in its center to support its trunk. The bark is ringed with woodpecker holes and a dead limb at the top is perfect for bird watching. It’s amazing the tree still stands, no less produces a healthy supply of fruit — that is, if we don’t get a late spring frost. Its apples are small and yellow with white flesh, not perfectly round, full of scabs, certainly not fit for modern grocery store shelves. The tree is unusual because it fruits in July.

“Oh, you have a July apple,” said a friend who grew up nearby. “It makes the best sauce.” When she said that to me, I’d never heard the term “July apple” before — and she was correct; the applesauce is delicious.

How old is that apple tree? I’ve long wondered. What kind is it? Is it wild or grafted? Who planted it? Probably not Johnny Appleseed (aka John Chapman), though he did spread his seeds near this western Pennsylvania farm around 1800. Might our tree have been growing in 1862 when Thoreau lamented in his essay Wild Apples that the era of the wild apple soon would be past? “I see nobody planting trees to-day in such out-of-the-way places, along the lonely roads and lanes, and at the bottom of dells in the woods,” he wrote.

When Thoreau wrote that essay, we had about 15,000 varieties of apples in this country, believed to have come from Kazakhstan via The Silk Road. (Only crabapples are native to our shores and they were called “spitters” because they tasted so bad that one wanted to spit them out as soon as possible. “Spitters” were made into hard cider.) Apples received a name only if they were grown from seed and tasted good enough to eat fresh and pass on to neighbors and friends, said David Benscoter, who runs the Lost Apple Project in Washington state, where he’s trying to save old apple varieties.

“Apples were incredibly important for homesteading families,” he said. “A family might plant as many as 100 apple trees to dry, make sauce, to can, for cider, and to make apple butter. Apples you could eat fresh from October until April or May were the most valuable of all.”

After the Civil War, commercial growers decided apples had to be big, red and uniform, and the varieties dwindled to about 5,000. From 1881-1945, according to the National Park Service, apple trees got smaller — from five feet tall to less than three — and went from a natural state to being pruned. “The development of Red Delicious during this period had an enormous impact on apple growing, resulting in greater profitability for the industry, great fashionability of red apples, greater ubiquity of a single variety, and further obsolescence of superseded varieties.” By the 1940s, Red Delicious was the most common apple.

“Everyone shares a little of the blame for losing these apples,” Benscoter said. “People bought apples with their eyes and only varieties with which they were familiar, like Red and Gold Delicious, Jonathan, and Mcintosh.”

John Bunker is trying to save old apple varieties too — in Maine, New England and New York. He’s an apple historian who founded The Maine Heritage Orchard, and he believes different genetic combinations may help fight apple diseases and pests and help trees deal with climate change — and he thinks old apples are simply magical. “Apple trees are important in about 50 different ways,” he said. “They connect people to history, place, families and their own past.”

They are emblematic of a whole culture, he said, teach us about the ground we live on, and unlock mysteries of those who came before us.

These old varieties might be the key to breeding the apples of our future, he said, and I was hoping our craggy old tree might be one of those keys.

Bunker told me there are many varieties yet to be rediscovered in places like our lawn, but that “time is of the essence.”

“The apples planted by the old settlers could live 100 to 150, maybe 200, years,” he said. “The last of those old trees are now coming to the end of their natural lives and are dying rapidly. The time is right now to find the last lost apples.”

Apples are difficult to propagate. One can’t just plunk a seed into soil and expect to get the same tree. That’s because apples are heterozygotes, meaning that “an apple tree from seed will not be a tree like its parent, but will resemble a more distant ancestor.”

That definition is courtesy of my great-grandfather Charles Burkett, who in 1903, with Stevens and Hill, wrote a book called Agriculture for Beginners. The only way to faithfully reproduce an apple is by grafting, and trees grafted onto modern dwarfing rootstocks don’t live as long as the old trees, Bunker said — only 30 to 40 years.

I figured my questions about our old apple tree were unusual but Bunker said no, such questions are being asked by countless people across New England who send him apples to date and identify. I did the same — 12 apples individually wrapped in newspaper, information about when our town was settled, and photos of the tree and its bark. I also sent him a photo of the tree from 1941 — so I know at the very least it was here then. I sent apples to Benscoter too, who passed them on to Shaun Shepherd and Joanie Cooper at The Temperate Orchard Conservancy in Oregon.

To determine what sort of apple I have, the two teams looked at fruit shape and skin color, and over a dozen other distinguishing characteristics, including the stem, calyx, core, sepals, seeds and stamen. “Identifying apples can be pretty picky work,” Bunker said.

Bunker knew of no cultivar called a “July apple,” a local nickname he surmised, and said he rarely sees summer apples at all. “If one had 50 trees, only one to two would have been summer apples.” He confirmed, however, that summer apples were generally planted next to houses, because they don’t store well and if not watched carefully and picked right away, they’d rot or get eaten by wildlife. I can attest to that.

In the end, each had a slightly different opinion. Bunker believes our apple tree “most closely resembles” an Early Harvest, 130 to 150 years old, a fairly common variety of summer apple in 1850. “High quality summer-ripening apples were uncommon overall, and when a good one came along — like Early Harvest — they were coveted,” he said. “Now, 170 years later, it is extremely rare, definitely an heirloom.”

Benscoter’s team identified our tree as Early Ripe, which likely came from a seed on a farm in Adams County, Pennsylvania, circa 1800, a rare apple first recorded in 1867, but not extinct. The two varieties are similar and apparently easily confused.

Bunker also concluded that our tree is grafted. That surprised me, because I see no evidence of grafting. “The graft on old trees is sometimes quite obvious,” he said, “and sometimes not visible at all.”

I may not save the planet with this old tree, but I’m happy to have narrowed the variety down to two possibilities. And I’m pleased to know about how long the tree has been here. I still don’t know if it was planted by the original settler who built this log house around 1860, or so we think, but I’m guessing it was. Still, in knowing what I now know, I feel somehow closer to those who walked this ground before me.

Whoever planted the tree sent me a gift, Bunker said. “Some people say, ‘I’m too old to plant an apple tree,’ but the people who planted that tree may never have eaten that apple,” he said. “Old apples are a gift from people long ago, saying to us: ‘This is for you.’”

What a gift, indeed — for those of us currently renting this small speck of earth — and for the wildlife with whom we share it.