Why We Ended the Program That Worked

“There is nothing more difficult than military combat.” — Sun Tzu, “The Art of War,” Chapter 7

In 1966, roughly 6,000 people lived in the village of Binh Nghia, a series of hamlets strung out along the Tra Bong River in far northern Vietnam, near the coast of the South China Sea, a mere 40 miles from Hanoi.

The village had been controlled by the Viet Cong for years, the South Vietnamese regular forces having been driven out of the area. Villagers were constantly shaken down, forced to supply the VC with food and intelligence, and young village men were drafted into VC cadres.

But once the Combined Action Platoon (CAP) moved in, things changed very quickly. When the combat skills of the U.S. Marines were combined with the local knowledge of the Popular Force militia, the Viet Cong were at sea. They had never encountered American forces that patrolled at night and who were as good at night fighting as the VC were.

It wasn’t smooth going, not by any means. Furious about being driven out, the Viet Cong convinced the nearby North Vietnamese regular army (NVA) to mount a large-scale assault on Binh Nghia.

At the time, the village was defended by only five U.S. Marines and 12 militiamen (the others being out on patrol). They were attacked by 140 heavily armed enemy soldiers. In that assault most of the marines in the village were killed, but they held out long enough for the Vietnamese militiamen to regroup and hold off the NVA assault.

In “The Village,” Francis J. “Bing” West, a marine field commander in Vietnam, tells the riveting story of the CAP unit at Binh Nghia and its successful attempt to pacify the village—so successful that Binh Nghia eventually became an R&R (rest and relaxation) site for South Vietnamese army soldiers. A bitter pill for nearby Hanoi.

Casualty rates among marines at Binh Nghia were high, thanks to the NVA attack described above, but overall casualty rates for CAP units were only half those of search-and-destroy patrols.

And their success was almost unbelievable: The Viet Cong never regained control of a hamlet protected by a CAP unit. By 1969, 114 CAP units (barely more than 1,500 marines) in northern South Vietnam were providing effective security for 400,000 Vietnamese people.

Unfortunately, in 1968 there were 16 million people in South Vietnam. Why weren’t more of them—why weren’t all of them—placed under the protection of CAP units?

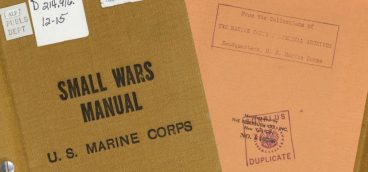

The answer is that almost every American commander in Vietnam had spent his entire career involved in conventional warfare: World War II and Korea, mainly. They had no concept of how to fight a guerilla insurgency, and the skill set and tactics required to be successful at anti-insurgency actions were simultaneously anathema and uninteresting to them.

To Westmoreland and his fellow commanders, if the application of massive force couldn’t win a war, they were at a loss. Tens of thousands of American boys died as a result of this myopia, and the inevitable revulsion against the conduct of the war would subvert discipline and cohesion in the U.S. military for years.

Operation Phoenix

“Warfare is the way of deception.” — Sun Tzu, “The Art of War,” Chapter 4

Sun Tzu was a huge proponent of battling insurgencies with counter-insurgencies, of fighting terror with terror, of disrupting and destroying an enemy’s intelligence network by whatever means was most expedient.

“The Art of War” devotes an entire chapter to “Employing Spies” (Chapter 13):

“Advance knowledge [of the enemy’s plans] cannot be gained from ghosts and spirits … but must be gained from men.”

“In general, as for … the men you want to assassinate … you must have spies search out and learn them all.”

The Phoenix program was inspired by the activities of the French Resistance in German-occupied France—or, for that matter, of Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh in Japanese-occupied Indochina.

William Colby, later CIA Director, oversaw Phoenix, applying lessons he had learned working with the maquisards (members of the French Resistance) after parachuting behind German lines in 1944 as an operative with OSS.

Broadly speaking, Phoenix was designed to identify and destroy the Viet Cong infrastructure in South Vietnam by infiltrating the VC civilian apparatus and neutralizing its members. Phoenix was astonishingly successful: More than 80,000 VC members were identified and either arrested, turned into double agents or killed.

After the war ended, the North Vietnamese acknowledged that Phoenix had been highly destructive to the Viet Cong, importantly contributing to the demise of the VC as an operational force.

So concerned was Hanoi about Phoenix that orders were given to kill anyone associated with the Phoenix program. Indeed, each regional VC cadre was given a quota: to identify and kill, for example, 1,400 Phoenix operatives.

Yet the Phoenix program was shuttered in 1972. Gen. Sun Tzu would have been horrified. Why would such a successful program, one of the few in the entire history of the Vietnam War (but see CAP, above), be shut down?

There were two reasons. The first was Tet-all-over-again. The American public was ultimately so repulsed by the conduct of the war that they didn’t care what the truth was about Operation Phoenix. Americans were prepared to believe anything negative about the war effort in general, and Operation Phoenix in particular, however obviously preposterous.

Certainly there were abuses. Neither the participants in Phoenix nor the fighters in the Maquis were choir boys, obviously, and it was probably a mistake to assign interrogations of captured Viet Cong suspects to the South Vietnamese. But antiwar activists vastly exaggerated the problems of Phoenix, including in Congressional hearings in 1971.

The wild claims of the antiwar crowd (I was a member of that crowd myself) were eventually discredited, but it was too late. America had had enough.

The second reason was that Westmoreland and his cronies despised the Phoenix program. It wasn’t “manly” or “soldierly,” and it wasn’t “search-and-destroy.” One is reminded of the preposterous discontinuation of America’s nascent cryptography program in 1929 because, as Secretary of State Stimson put it, “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail.”

Similarly, Westmoreland apparently believed that it was better for American soldiers to die than for himself and his senior officers to get their fingers dirty in anti-terror activities.