Why Are We So Afraid of Democracy? Part II

Profound disagreements among the voting public have led, as noted in my last post, to profound disagreements in Congress. This has, naturally enough, led in its turn to a substantial decline in collegiality, willingness to compromise, and even civility in that not-so-august body. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that Congress has accomplished hardly anything since Obamacare was rushed through the House and Senate while both bodies were, very temporarily, in Democratic hands.

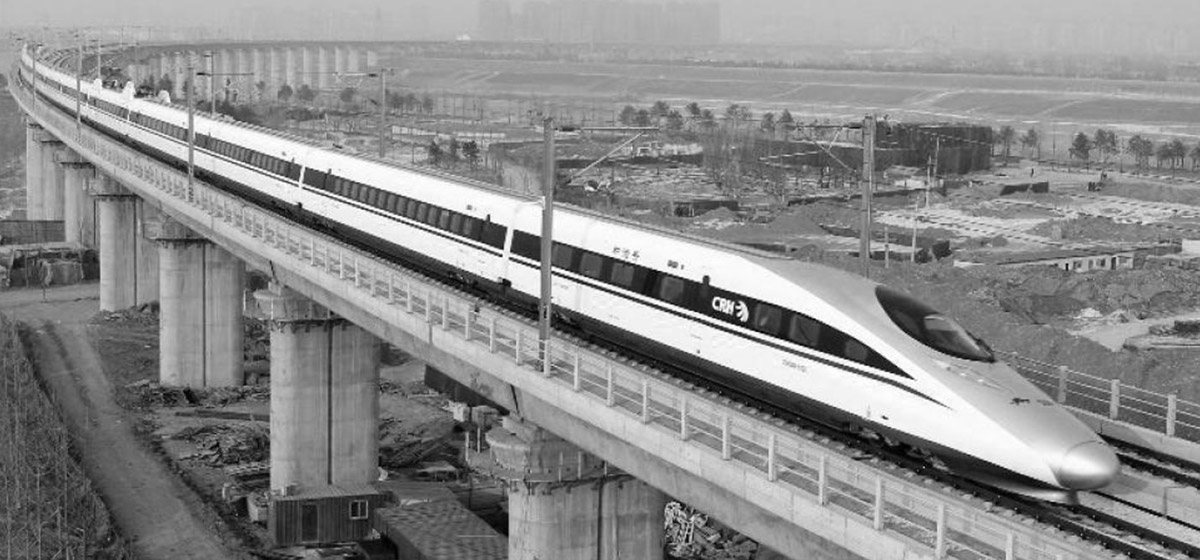

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, China was forging ahead, growing at an annual compound rate north of 10% for 30 years running. Vast new cities were constructed, high-speed trains raced hither and yon across the trackless Chinese countryside. As issues arose, decisions were made, actions were taken. The contrast with a moribund and checkmated Congress could hardly have been more stark.

There are dozens of books and articles(1) espousing the superiority of the Chinese system, and even more TED talks if you like that sort of thing. And why not? The Chinese Communist Party vets its members over many years, promoting the best of them and giving them greater and greater experience. By the time Party members reach the upper echelons of the system – the Central Committee or just below it – they are the best-of-the-best. It’s an aristocracy and it’s hard to argue with results, especially compared to the qualifications required to enter the US House of Representatives (be 25 years old and have a pulse).

Except the results actually aren’t so good, for two reasons. First, it’s true that after Deng Xiaoping introduced free market elements into the Chinese centrally-controlled economy, growth took off. But many industrializing societies experienced similar growth in the past, including the Soviet Union between 1917 and World War II, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore – even the United States in the 19th century.

Second, the 30 years of rapid economic growth between Deng and the Financial Crisis were terrific, but what about the 30 years before that, under Mao? If you average the chaotic Mao years and halcyon post-Mao years together, things look a lot less rosy for the Chinese system.

The real question for China, though, is where it goes from here, economically speaking. For now China is stuck in the so-called “middle income trap.” Rapid industrialization raised incomes to something like a lower middle class level (on a purchasing power basis), but there is little evidence that China will make the transition to a post-industrial economy driven by technology and services. That would require that businesses and consumers be given vastly more freedom to produce and consume what they wish. Is Xi prepared to move toward greater human freedoms?

Not likely. Deng and his successors followed a consensus-driven governance model that discouraged extreme opinions and attitudes. But Xi is a throwback to Mao. He has built a cult of personality around himself, has assumed every title the Chinese system has to offer,(2) and is ruthlessly eliminating rivals. Corruption is breathtakingly endemic at every level of the Communist Party apparatus, including “Mr. Panana Papers Xi” himself. The slightest dissent is dealt with simply by having people disappear. It’s true that Americans who admire the Chinese system don’t admire these aspects of it, but it’s one piece of whole cloth. Like it or not, absolute power really does corrupt absolutely.

Many experts worry that the Chinese leadership lacks the skillset to engineer a transition to a post-industrial future. I happen to agree – the dazzling incompetence the leadership demonstrated during last year’s Chinese market meltdown would be Exhibit A. But that’s not the crux of the problem. The heart of the matter is that the leadership is damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. If China doesn’t make the economic transition, pressure from the population will lead to acute civil strife that can be contained only by ramping up repressive security activities. That’s where Xi is headed now.

On the other hand, if China does make the transition, the current Chinese leadership will be jettisoned. You can’t be economically free and politically unfree.(3)

Democracy-challenged governments follow a familiar pattern: short-term efficiency that turns quickly into a pig’s breakfast. The Central Committee decides that giant new cities need to be built in Kangbashi, Yujiapu and so on, that hundreds of new soccer stadiums are required, that vast housing tracts are urgently needed. Bingo, there they are. Except that – oops – nobody’s home. These are Ghost Cities, Ghost Stadiums, Ghost Neighborhoods.

This isn’t specifically a problem for communist governments, it’s a problem for the absence of democracy everywhere. Consider the European Union. All the countries of Western Europe are representative democracies, but the EU itself is a whole other kettle of dead fish.

Like China, the EU preserves the hollow forms of democracy – there is a European Parliament, for example. But this august body boasts – are you holding onto the wall? – 751 representatives from 28 countries speaking God-knows-how-many languages. Many of them can’t stand the sight of each other. No one in Europe knows or cares what the EU Parliament is doing, it simply has no legitimacy as a democratic institution. The result is that all important decisions are made by the undemocratic European Council (made up of the heads of state of member governments). It’s hardly a wonder that the EU lurches from crisis to crisis like a headless wind-up doll.

Next week we’ll look at one other reason why our faith in democracy has been undercut in recent years.

(1) As a random example, Thomas Friedman has praised China’s one-party dictatorship as having “great advantages,” one of which is that it is led by an “enlightened” leadership. Breathtaking, really.

(2) “[Xi] is not only party leader, head of state and commander-in-chief, but is also running reform, the security services, and the economy. In effect, the party’s hallowed notion of ‘collective’ leadership … has been jettisoned. Mr. Xi is … ‘Chairman of everything.’”

(3) This is pretty much a universal truth, but it’s also easy to understand in concrete terms. If Chinese businesses were economically free someone would quickly invent a way around the current Internet censorship in the country, and if consumers were economically free they would certainly buy that technology. After that, the half-life of the Party’s Central Committee would be measured in months.