When Clocks Have No Hands

I am a returnee by nature. Over the

years I have returned to neighborhoods where I once lived, to rooms in dormitories that were mine, to Mirror Lake in the Adirondacks where I caught my first trout and to a grade school playground where I competed in kickball (soccer), softball and football.

Although I enjoyed each of these returns for different reasons, it was a return to Notre Dame in 1999 for the 50th reunion of my 1949 graduating class that taught me what returning really meant. At first I was reluctant to go. I had seen how “folksy and clubby” some reunions could be, but my wife, Mary Anne, for whom Notre Dame was primary, convinced me that the reunion would be a once-in-a-lifetime event. It was and still is.

The first thing that a reunion makes an attendee aware of is change. This became evident to me when another attendee approached me and asked, “Weren’t you Sam Hazo?” When I smiled, he repeated, “I mean didn’t you used to be Sam Hazo?” He simply was saying what he saw, and it took a few moments for the past to fuse with the present tense.

My undergraduate years were 1945 to 1948 (actually 1949 but by going to summer sessions for financial reasons I shortened my college years). Tuition, room and board for me then amounted to $400 a semester plus a job. By the time of my graduation it rose to $800 per semester. This was also the era when the Notre Dame national championship football teams in 1946 and 1947 were quarterbacked by All American and Heisman Award winner Johnny Lujack (born and raised in Connellsville) and would become for me and many the greatest teams of the 20th century. (I never saw Notre Dame lose a game.) All of these memories coalesced during that reunion. Despite Thomas Wolfe’s claim that “you can’t go home again,” I learned gratefully that you can as long as your return transcends mere nostalgia and touches on more universal feelings.

What stayed with me permanently from the 1999 reunion was that I was completing a cycle of departure, absence and return, and that this completion evoked other parallels. It made me regard the common practice of people who leave their homes in the morning to go to work and then return in the evening as a similar cycle. And such returns universally afford the returnees with a sense of satisfaction that nothing else can match.

Travelers feel the same when they return to the United States after a vacation or an extended stay in Europe or Latin America. Because they are returning from a foreign country, they come to appreciate with renewed feelings what it means to come back to their native country, their own state, their own city, their own neighborhood and ultimately the house they know as home.

For all too many years now we have seen American service men and women return from stints in Afghanistan and Iraq. The way they embrace their parents, wives, husbands, children or other family members reveals a joy and gratitude that are without equal. They complete the most basic of human cycles by returning—by coming home.

This theme of return—of coming back to origins—is quite common in literature. Homer’s “Odyssey” is a chaptered epic narrative of one man’s journey or odyssey through 20 years of war and struggle to come back to Ithaca. After surviving numerous challenges and threats, he is reunited with his faithful wife Penelope and his devoted son Telemachus. The fact that the “Odyssey”

has endured for millennia in innumerable translations confirms that coming home and reuniting with loved ones is a universally understood longing.

The closest parallel in English is probably Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “Enoch Arden,” the story of a man who becomes a sailor out of desperation to provide for his wife and who, after surviving shipwreck and years of primitive life on a remote island, returns to find his wife remarried and a mother. Unwilling to destroy his wife’s happiness in her second marriage, he never reveals himself to her or anyone and dies in solitude.

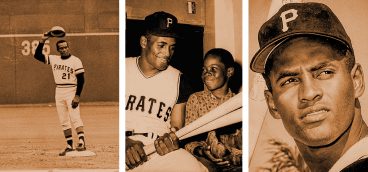

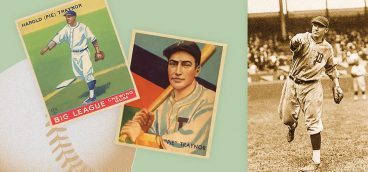

As farfetched as it may appear in contrast with literary classics, I even find an echo of this theme in my favorite sport—baseball. Home plate is central. It’s where the game begins when the batter stands in the batter’s box and prepares to hit a ball that the pitcher wants him to miss completely. Even if he hits the ball, there are eight players plus the catcher who are poised to catch the ball and thwart his effort to return home via first, second or third base.

Because the clock is not involved in baseball, time makes no difference. The players even run the bases counterclockwise as if to show how the game disregards time completely. The core of the game is to begin from home and return home safely although the rate of success for even the best players is in the area of 8 percent every time they try. Absurd as the odds make it appear, the game of baseball goes on, and arriving safely and victoriously home is the goal.

If sports are what the poet John Ciardi defined as “activities made difficult for the joy of it,” the transcendental meaning of home and return certainly exceeds the meaning it has in sports. Where the emphasis in a game like baseball is to score by crossing home plate safely, the meaning of returning home from travel or work is closer to a reunification.

In personal terms it can mean reuniting with our very selves in ways that help us feel whole again. Recently I saw a documentary of the life of the deservedly honored Hollywood director Steven Spielberg. Raised in an Orthodox Jewish family, Spielberg separated from Orthodox Judaism as he grew older. He retained his Jewish identity, but it seemed more and more like an affiliation until he worked on and completed his direction of the award-winning film, “Schindler’s List.” He spent weeks and weeks in Krakow as well as other sites in Poland where the Nazis incarcerated and murdered the Jews. At the conclusion of the filming, Spielberg said he felt he had returned and connected with his real identity, and he added that he has retained that feeling ever since. In effect, he had reunited spiritually with his real self. He specifically used the word “reunification” to describe this phenomenon. Spielberg’s experience of “reunification” transferred the drama of the urge to return home into something spiritual rather than geographic.

This confirmed for me that the ultimate virtue of hope is what ought to motivate us to live charitably together until that time when life for each of us is not taken away but, in the coda of many religions and biographies, changed. Those who have lived a loving life hope to discover that death is trumped by love because love does not die when the person loved dies. Instead love intensifies.

For me this has always been the existential guarantee of most religions, namely, that the gift of faith in a life hopefully lived and motivated by love for (or kindness to) others is a preview of immortality. To be reunited in eternal love is the fulfillment of that hope.

For Christians the life of Christ is essentially a saga of divine union followed by communion with other human beings for 33 years and then ultimately culminating with divine reunion. This sounds rather catechetical even as I write it, but it is no more deniable than Steven Spielberg’s feeling of reunification with or discovery of his true self after a lifetime of disaffection.

Returning in 1999 to be with my fellow graduates was, as I have noted, more than just to join a gathering. It was a return to a time of life that created the time that followed. What lives we created for ourselves as alumni between 1949 and 1999 was traceable to what we learned in our undergraduate years. We “sized up” one another at the reunion in that spirit. We found that our friendships had endured the test of time.

I did not have a similar sense when I attended a Quantico 50-year reunion with my fellow Marine Corps officers in 2002. Although I still stay in touch with men from that group, I never have the same sense of intellectual solidarity that I felt in 1999. It shows me the difference between comradeship and friendship.

The emphasis in the military is on the former, and it is enforced by team discipline, orders and mutual dependence. As one to whom obedience to one’s conscience is the ultimate loyalty, I have a guarded skepticism about blind obedience to superiors, whether the setting be military, governmental, ecclesiastical, commercial or academic. For me there is no substitute for intellectual freedom and the exercise thereof. That may explain why the reunion of 1999 was more significant for me than the 2002 reunion at Quantico.

Returning to one’s true self makes such returns more and more like what Robert Frost would have called a “retreat”—a temporary withdrawal from action. The returnee leaves the present tense of his life to discover and reunite with a time which, though past, is ever present. The very essence of happiness is in that reunification. It creates a moment of complete fulfillment—a moment that cannot be measured by time because

it is beyond time—a moment in and of

itself.