What is Pittsburgh?

Before Pittsburgh became a place, before it was an idea, before its stories, its heroes, its villains, its tales of exploration, adventure, discovery and struggle became part of the popular imagination and American life, it was a space defined only by the movement of water through mountains, valleys, forests and a dark wilderness.

A young George Washington was among the first to see the land for something other than its natural state. “Extremely well situated for a fort, having command of both rivers,” the future U.S. president said in 1753, while scouting the North American frontier for the British. “Very convenient for building.”

By the time John Forbes carved his way through the Pennsylvania forest to the same spot five years later, Washington at his side, the victorious war general had not only wrested the most strategic spot in North America away from the French and claimed it for the English crown, but it was left to him to give the prize a name. Forbes called it “Pittsborough,” after British Prime Minister William Pitt, and referring again to its potential, he told his boss back in London that England now owned “the finest and most fertile” of any land in North America.

From that village, that British fort, came the first efforts to define Pittsburgh (its second name) as a place that exists as much in the mind and the imagination as it does on a map. The efforts have continued since, to give it an identity, to pronounce its importance to the wider world and to answer the question: What is Pittsburgh?

The questions of identity and image stir fierce debate as the city still struggles to overcome the psychological crisis that accompanied the most severe manufacturing decline of any major metropolitan area in the country.

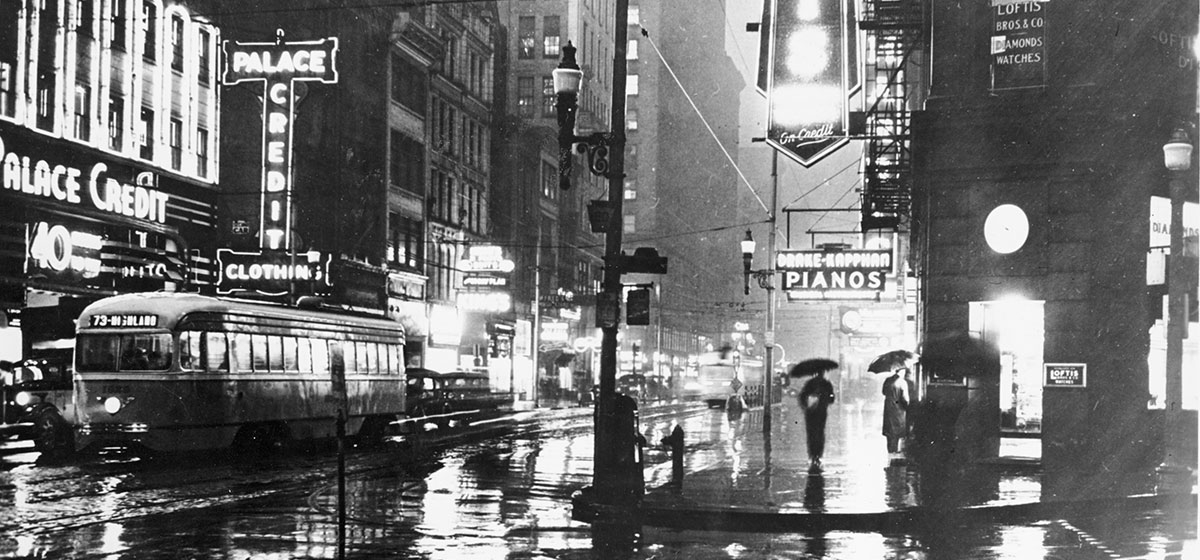

It may no longer be the “Steel City,” but that moniker still resonates around the world, abetted by the popularity of the Pittsburgh Steelers and the powerfully artistic black-and-white images of smoke, brick, ash and fire that circulated in the popular magazines of the mid-20th century, flashes that remain fixated on the consciousness like the glow from a camera bulb.

This crisis, though, is nothing new. In fact, one could argue it is almost two and half centuries old. It dates to Pittsburgh’s founding, the struggle for land and the bludgeoning of bodies with swords, muskets and tomahawks in the 1750s. From the beginning, there was a duality about Pittsburgh, a place beautiful and scarred, rich and poor, creative and plodding, cultured and crude.

Every attempt to form just one message, one identity, has fizzled, failing to connect both with the wider world and with a local audience. Still, people remain convinced that it can be changed, altered, reshaped. And maybe it can. “It is time for the next evolution of our brand, our image,” said Andy Masich, president of The Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center. “And I would say we don’t quite have that. It hasn’t crystallized yet.”

But images and brands and advertising slogans (“City of Champions,” “Pittsburgh, The City With a Smile on its Face”) flicker and fade (how many still remember when Pittsburgh was the “Gateway to the West”?). Cities also by their very nature are ever-changing, decaying and springing to life again, paved over by new ideas, people, structures and layers. In “The Waste Land,” poet T.S. Eliot refers to the “Unreal City,” an ephemeral place that exists largely in the imagination. Buildings and castles may rise and fall, but the name lives on forever.

And so it is with Pittsburgh, a city that summons a classic, mythical narrative of antiquity: a violent beginning, a brilliant maturity, a dramatic fall. Then, miraculously, a re-birth. Pittsburgh simply will not give up. Not after a fire that destroyed one-third of its buildings or a flood that submerged Downtown. Not after the outbreak of disease wrought by the choke of industrialism nor the economic collapse of the steel industry, which put more than 100,000 people out of work.

A city that shaped the world

While coming back, again and again, Pittsburgh changed the world. It is here where Washington, who nearly died several times during the French and Indian War, learned the courage he would use to lead the American Revolution. It is here where the British won that war — the first to span the world — and set the table for the revolt of American colonists against the crown. It is here where the American West truly did open up to settlement via the Ohio River, the superhighway of the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Pittsburgh is the city where post-Civil War America found the cheap steel to build its railroads, skyscrapers and bridges, totally reshaping the urban landscape. It is Pittsburgh that squeezed out more than a quarter of the nation’s steel during World War II, a massive production effort that helped defeat Adolf Hitler and prompted the secretary of the Navy to say, “Every time I approach Pittsburgh, especially by plane, I get a sense of tremendous power, a sense of accomplishment.” Pittsburgh was also the first major U.S. industrial metropolis to clean itself up, to beat back the floods and the smoke. To build parks and roll through entire neighborhoods with bulldozers in a new experiment known as “urban renewal.” Some projects worked (The Point) while others ruined the social fabric (Hill District) or killed off what was a vibrant shopping center (East Liberty).

But these were all grand gestures. Big, bold moves.

Drama: It’s everywhere in Pittsburgh. The hills and buildings and bridges that stand up and look you in the face. The blood and tears of old battles, of Indian bones. The teeming ambition. And, of course, the piles of money. When bobbin-boy-turned-steel-magnate Andrew Carnegie sold his empire to J.P. Morgan in 1901, he became the richest man in the world and created three dozen millionaires overnight. Tales of their lavish, outrageous spending, the so-called “Pittsburgh millionaires,” appeared in news- papers around the country. It was Carnegie and Mellon and Hunt and Frick and Oliver and Phipps and so many others who turned the city into perhaps THE laboratory for modern capitalism, a place where labor unions staged bloody battles and business titans tested boundaries.

The town became a place of ever-present movement — of Robert Fulton’s steampowered ship in 1811, the first to travel Western waters, of the black migration northward captured in August Wilson’s world-famous plays, of the launching of Lewis and Clark’s boat from the Monongahela River, of the natural ebb and flow of water and hillside inclines and cars and trucks and trains and barges, every day.

It became a place of immense brainpower and creativity, home to the problem-solving genius of Saxonburg’s John A. Roebling, an engineer who designed the first wire rope bridge and the first cable suspension bridge before designing the mighty Brooklyn Bridge. Or the wild inventiveness of George Westinghouse, creator of the railroad air brake and the technology necessary for long-distance transmission of electricity. Or the brash salesmanship of H.J. Heinz, who fought back from bankruptcy to put a ketchup bottle on nearly every kitchen table in America.

It produced the kick, spin and dash of East Liberty’s Gene Kelly, around a lamppost, holding an umbrella in the movie “Singing in the Rain.” The stumble and scoop of Franco Harris as he cupped the “Immaculate Reception” and rambled into the end zone. The roar of Mike Fink, 19thcentury keelboat driver and folk hero who died a mysterious death out West. The surgeon’s touch of UPMC transplant pioneer Thomas Starzl, the medical brilliance of Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh, and the formidable brainpower of Carnegie Mellon University — laboratory for the pings, pangs and dings of robots and computer science, creator of an Internet shorthand language best represented by the now-ubiquitous smiley-face icon: 🙂

Despite the undeniable accomplishments, it is hard not to dwell on labels, on image. One that has stuck the longest, though, illustrates the duality of message inherent in any discussion of Pittsburgh: “Hell With the Lid Taken Off.” The infamous tag, authored by journalist James Parton in 1866, evokes the smoke, fire and toil of the day. But in using the phrase, Parton touched on something else just as powerful and just as lasting. He hoped to capture, in words, the drama of the city, as he climbed atop a hill, just as Washington did, and gazed upon the “most striking spectacle we ever beheld.”

Parton knew then what we know now—Pittsburgh is one hell of a story. “This is one of the most interesting places in all of America,” said historian, author and Point Breeze native David McCullough, speaking last spring at The Pittsburgh Hilton to a national group of educators. “There is no other city like it, and it remains distinctively itself, year after year, for all of the changes that have taken place, for all of the setbacks the city has experienced.”

The importance of the past

It is impossible to talk about Pittsburgh without consulting what has gone before. “We live not only in the city that we see but also in the memory that predates the present and underscores it with images that exist nowhere but within us,” wrote Pittsburgh poet Samuel Hazo, in “The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You.” Interviewed at Carlow College where he runs the International Poetry Forum, Hazo said it is difficult to attach one singular image or identity to Pittsburgh, and that Pittsburgh “means something different to everyone who has lived here.”

But can a city define itself by what happened before? Is that healthy? McCullough, one of the country’s best-known historical authors, says “yes,” that the city’s importance must be viewed through its contributions to the development of the United States. In fact, he uses Pittsburgh as a metaphor, a lens through which he can view the entire history of North America. “I really don’t think there would be a better place to put that lens down than here,” in southwestern Pennsylvania, he said in an October speech to a group of local engineers. History, to McCullough, presents Pittsburgh with a clear picture of what it will be in the future: a city able to “cope with difficult times and … solve difficult problems.”

In a recent speech on the topic, he began with the tale of the Bantam Car Company, a Butler outfit trying to introduce the midget automobile, with no success, in the 1930s. As the company was about to go bankrupt in 1940, it received a request from the U.S. Department of Defense for a small vehicle weighing no more than 2,000 pounds that could navigate a slope of 40 degrees and be easy to repair. According to McCullough, the firm made a bid, one of 134 manufacturers to do so. At a diner in Butler, several men scratched out a design on napkins of a Jeep.

Bantam won the design prototype competition, but the contract to build the vehicles went to a firm in Toledo, Ohio. But that outcome hardly diminishes the lesson for McCullough, who said it illustrates a theme of life in southwestern Pennsylvania — people who were “down but not out” and decided to try again anyway — and how this area has so greatly influenced American life. “It would be hard to pick something that is more American, more representative of our culture, our society, our productive capacity and a kind of toughness, than the Jeep.”

He asked his audiences to consider the other bits of Americana to emerge from Pittsburgh:

- The first movie theater (the Nickelodeon, Downtown)

- The first gas station (introduced by Gulf, in East Liberty)

- Daylight savings time (championed by Pittsburgher Robert Garland in 1918)

- The first radio station (KDKA)

- The first public television station (WQED)

- Lewis and Clark’s boat

- The steel gates of the Panama Canal

- The propeller in Charles Lindbergh’s plane

- The first real use of natural gas

- The start of the oil industry (just north of Pittsburgh)

- The Big Mac (created in 1967 at a Uniontown McDonald’s)

“Could you think of anything more American than Heinz ketchup, or the pull-tab top on your beer can, which was done by Alcoa for the Fort Pitt Brewing Company?” McCullough said. “If you have ever played Bingo (created here by Hugh Ward in the 1920s), if you ever had a banana split (invented by a Latrobe pharmacist in 1904), if you’ve ever ridden a Ferris Wheel (invented by Pittsburgh native George Washington Ferris in 1892), all of that began right here in Pittsburgh.”

One thing that “truly changed America,” in McCullough’s words, was the advent of the Bessemer steel-making process, which made steel much more inexpensive and provided the skeletons for skyscrapers, bridges and railroads — the framework of modern America. One of the first to develop the Bessemer steel-making process was local engineer John Fritz, at the Cambria Iron Co. in Johnstown. Fritz worked for months building a new piece of machinery, and one morning, as McCullough tells it, he called all his workmen together: “All right boys, let’s start her up and see why she doesn’t work.”

“That is very American,” McCullough said, and also “very western Pennsylvanian. Not doing it exactly by the book, not doing what we know will work, but doing what we want to see happen and then figuring out why it didn’t work and fixing it and making it work.”

For McCullough, of course, the story of Pittsburgh is personal. He spent his boyhood here and remembers what it was like in the mid-20th century, living through a war and feeling “in the midst of history.” When the collapse of the steel industry came, it was a shock to his dad, who used to say at the dinner table that there would always be a demand for steel, that the Pittsburgh coal “seam” would last for 500 years and the city would thrive forever. “In his lifetime, he saw that all change, and that was as shattering, I think, maybe as much as the Depression,” McCullough said. “Suddenly this powerhouse was no more. But it didn’t die, Pittsburgh. Great cities don’t die.”

War of words

From the beginning, Pittsburgh had its detractors. Diplomat Arthur Lee, a delegate to the Continental Congress who worked in Paris alongside Benjamin Franklin, passed through Pittsburgh on Dec. 17, 1784 and dismissed it immediately: “The place, I believe, will never be very considerable.” Dr. Johann Schreptf, a German doctor who toured the U.S. and came through Pittsburgh in 1783, called Pittsburghers “extremely inactive and idle,” distracted by “comfortable sloth.”

So began the Pittsburgh PR war and the duality of image, of identity, that runs throughout Pittsburgh’s history and characterizes the debate today.

One of the first to fire back was Pittsburgh lawyer Hugh Henry Brackenridge, in the first issue of the Pittsburgh Gazette, on July 29, 1786, producing a wildly optimistic view of the young city and arguing that it offered the best of everything. “Here we have the town and the country together. There is not a more delightful spot under heaven to spend any of the summer months. Here we have the breezes of the river, coming from the Mississippi and the ocean; the gales that fan the woods, and are soft from the refreshing lakes to the northward.”

In a subsequent article, Brackenridge, who founded the University of Pittsburgh in 1787, made a prediction that must have seemed outlandish but, in fact, was prescient: “This town in future time will be the place of great manufacturing. Indeed the greatest on the continent, or perhaps in the world.”

Still, many of the first prominent visitors were not impressed with a place alternately known as “Gateway to the West” and the “drinkingest town” in the West. Charles Dickens didn’t like it. Visiting in the spring of 1842, he compared Pittsburgh to bleak Birmingham, England. “It certainly has a great quantity of smoke hanging over it.”

English author Anthony Trollope, in 1862, called it the “blackest place I ever saw.” But outsiders paid attention, nonetheless. If Pittsburgh had an image, it was as a confident industrial power teeming with energy and ingenuity, in pursuit of wealth and work. But the bad press continued, furthering the duality of image. Railroad riots in 1877 killed 40 people. An 1892 strike at the Homestead Works killed 10 and led to an assassination attempt of Henry Clay Frick, the man running the plant for Carnegie, who was in Scotland at the time.

Carnegie’s reputation — and Pittsburgh’s — suffered as a result of the Homestead strike, which attracted more than 100 reporters from the U.S. and abroad. His relationship with Frick suffered, too. Their split, which spilled out in court, was also the subject of newspapers here and around the country. Late in life, when Carnegie tried to reconcile with Frick through a messenger, the response from Frick was: “Tell him I’ll see him in Hell, where we are both going.”

Carnegie, after he made his millions, never lived in Pittsburgh. But he wanted visitors to see what he had done here. One such visit was a disaster. He invited English philosopher Herbert Spencer to tour the mills, and Spencer — who pushed a theory of “Social Darwinism” that justified Carnegie’s grand accumulation of wealth — hated what he saw. He nearly collapsed from the heat of the Edgar Thomson Works, in Braddock. Standing on a hilltop in Homestead, he said that “six months residence here would justify suicide.”

The apocalyptic comments continued into the 20th century. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, when asked what he would to do to fix Pittsburgh, said: “It would be cheaper to abandon it.” While the rhetoric changed once Pittsburgh began cleaning itself up in the 1950s and 1960s, the dramatic language of Pittsburgh’s detractors remained, repeated over and over again for effect.

Forgotten are those who saw Pittsburgh in a different way. U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt, for example, loved it. In a 1917 speech to the Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce, he said “there is no more typical American city than Pittsburgh. And Pittsburgh, by its Americanism, gives a lesson to the entire United States. Pittsburgh has not been built up by talking about it. Your tremendous concerns were built by men who actually did the work. You made Pittsburgh ace high when it could have been deuce high.”

The glamour of change

Clyde Hare is one of the few still living who participated in the greatest image campaign ever produced by Pittsburgh — one so powerful that it is with us still, 50 years later, and defines for many the identity of this city. He was one of 14 photographers invited to Pittsburgh in 1950 by the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, a public-policy group that emerged after World War II to tackle some of Pittsburgh’s problems. Hare and others documented the many changes of Pittsburgh’s Renaissance — an ambitious attempt to remake the urban landscape of Pittsburgh.

Starting with Downtown and The Point, the attempt was led by forceful Democratic Mayor David Lawrence and powerful banker Richard King Mellon, the two forming a legendary partnership that produced a spate of projects in the 1950s and 1960s. Hare, recalling what that time was like in 1950, described his routine. He would get up every morning, eat something (usually bread and cheese) and shoot pictures all day long, “till I dropped,” he said. “I did that for three years.”

In November, at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Hare showed some of his photos and those of his colleagues. Click… The Lower Hill before urban renewal… Click … Buildings near the Point being demolished for a park and office buildings… Click… Little boys lined up for a show at the New Grenada Theater, dressed in little suits… Click… A man on a construction beam, high above the city… Click… Asteam train passing in the night, the smoke rising above Mount Washington.

As Hare cycled through image after image, it was clear how these photographs define our view of the city and how that view remains black and white. The same can be said for the pictures of Eugene Smith and Teenie Harris, all set in the mid-20th century, all capturing the drama of daily life, the sadness, loss and hope. With this art, there is a dual message — the same split identity that has characterized Pittsburgh over time. Partly, it is the view first reflected in art by Louis Brantz, who painted the earliest-known portrait of Pittsburgh in 1790 and called the land and rivers: “the most beautiful I ever beheld.”

But there is a darker view, as well. An acknowledgement that not all is well in Pittsburgh, that the toil that made Pittsburgh important came at a price. Perhaps because these images are so memorable and because no others have replaced them, much of the darkness stays with us, despite the many changes to Pittsburgh the last half century, despite the cleaner air and the brighter sky.

There is a glamour to the darkness, as well, and the rush of escape. This urge may first have been captured in Willa Cather’s 1906 short story “Paul’s Case,” written while the well-known author lived on Murray Hill Avenue in Squirrel Hill. It is about a teenage boy in Pittsburgh who wants to get out, away from the conformity and despair of life in Pittsburgh. He steals some money and escapes to New York. He lives the good life for a few days, in a fancy hotel, realizes the folly of it all, and commits suicide.

Another real-life boy who wanted out was, famously, Andy Warhol. Gerald Stern, a poet who grew up in Pittsburgh and now lives in New Jersey, drove Warhol to the train station, on his way to New York. “I think he loved Pittsburgh,” Stern said. But, “he wanted to hang out with rich people on Long Island. His dream came true.”

The list of famous artists who left is long: Kelly, Billy Strayhorn, Lena Horne, Perry Como, Bobby Vinton, Shirley Jones, Mary Lou Williams, Errol Garner, Martha Graham, Gertrude Stein, Mary Cassatt, Jimmy Stewart, John Edgar Wideman, Annie Dillard, August Wilson, Dennis Miller, F. Murray Abraham, Jeff Goldblum, Christina Aguilera, Michael Keaton and Stewart O’Nan.

In an e-mail, O’Nan, an author, said the city he grew up in “is gone, along with most of its good-paying factory jobs and blue-collar middle class.” What lingers is “the myth of work — That there is always more work to do. That if we work hard, and all work together, we will all succeed.” That myth, he said, now is a “spirit, but like a defeated nation’s once-glorious past, revered all the more for it. It’s no wonder Pittsburghers of generation on generation (maybe those younger than mine, that never witnessed even the end of the boom) carry a civic pride for a Pittsburgh that no longer exists.”

Stern said writers and poets have a “lovehate relationship with Pittsburgh.” Writer Albert French, Wideman’s cousin, argues that Pittsburgh is still not supportive of artists, which is why they want to leave.

This reluctant view of the city has found its way into popular culture, from comics to the movies. Plenty of Hollywood one-liners have been written at Pittsburgh’s expense, especially in films that appeared through the 1940s and 1950s, according to local independent filmmaker Tony Buba. One such movie, 1958’s “Auntie Mame,” focuses on the story of an orphan and her aunt.

Orphan: “Is the English lady sick, Auntie Mame?”

Auntie Mame: “She’s not English, darling… she’s from Pittsburgh.”

Orphan: “She sounded English.”

Auntie Mame: “Well, when you’re from Pittsburgh, you have to do something.”

Years later, Pittsburgh remains a periodic gag. A Calvin and Hobbes strip, from the 1990s, captures the same message. Calvin, a precocious boy, and a tiger, Hobbes, are lying on a hill, staring into the sky.

Calvin: Where do you supposed we go when we die?”

Hobbes: “Pittsburgh?”

A pause.

Calvin: “If we’re good or if we’re bad?”

The importance of the past

Most artists agree, though, that Pittsburgh still captures the imagination, and with imagination there are dreams. One Wideman story, called “backseat,” describes a trip up a Mount Washington incline, and his view of the city. “I was mesmerized by the tapestry of lights that winked and twinkled brighter than stars.”

Stern agrees, saying of Pittsburgh: “Geographically, it has great drama.” The hills, the rivers, the ups and downs “give it romance, a dynamism and a mystery, unwittingly.”

Which brings us back to what George Washington saw in 1753, at what is now the Point. Pittsburgh, as a place, is what we want it to be, but there is something about it that no image campaign, no one-liner, no invention will ever change. And that, in the end, is what we will remember.

Writer Annie Dillard, in her memoir of Pittsburgh, “An American Childhood,” addresses this when she writes about what she will be able to recall late in life, “when everything else has gone from my brain.”

“What will be left, I believe, is topology: the dreaming memory of land as it lay this way and that. I will see the city poured rolling down the mountain valleys like slag, and see the city lights sprinkled and curved around the hills’ curves, rows of bonfires winding… the three wide rivers divide and cool the mountains. Calm old bridges span the banks and link the hills… Where the two rivers join lies an acute point of flatland from which rises the city. The tall buildings rise lighted to their tips. Their lights illumine other buildings’ clean sides, and illumine the narrow city canyons below, where people move, and shine reflected red and white at night from the black waters. When the shining city, too, fades, I will see only those forested mountains and hills, and the way the rivers lie flat and moving among them, and the way the low land lies wooded among them, and the blunt mountains rise in darkness from the rivers’ banks.”