What Happened at Thompson’s Island?

Were you to launch a canoe at the U.S. Forest Service Buckaloons boat ramp, where Brokenstraw Creek enters the Allegheny River, then float down toward the borough of Tidioute, the setting would appear much as it must have to a party of Seneca Indians paddling the same route in the late summer of 1779. Carried on the Allegheny’s strong current, you would steer a course, just as they did, among lush islands under forested bluffs that confine the flow. And somewhere among the meandering channels, you would pass a place where those earlier paddlers encountered the advance guard of Col. Daniel Brodhead’s campaign upriver into the Seneca homeland. Exactly what happened in those ensuing minutes cannot be known, but history recalls the event as The Battle of Thompson’s Island.

The long-accepted history hinges on a brief report Brodhead wrote weeks later to his commanding officer, Gen. George Washington, that was lavishly wordy in the style of the day but vague on details. Last fall, cooperating partners with an interest in the upper Allegheny region and its history searched the river corridor for the site of the skirmish, and clues it might yield to events lost to time.

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission—supported by Friends of Allegheny Wilderness, the Seneca Nation of Indians and the U.S. Forest Service—sought and won a grant from the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program to find the uncertain site. The partners engaged Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. of Jackson, Mich., to conduct archaeological field work, host public meetings and publish a final report. The project’s goals were to provide a historical and geographic narrative of Brodhead’s 1779 expedition and verify the battlefield’s location.

“The Battle of Thompson’s Island project is fascinating because it has attracted such a unique collection of partners to explore this chapter in American history,” said Kirk Johnson, executive director of Friends of Allegheny Wilderness. “The event was the only acknowledged Revolutionary War action to take place in northwestern Pennsylvania, and the upper Allegheny islands today represent living history. Now protected as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System, Thompson’s and six other islands will remain much as they were when the Seneca people hunted and fished there.”

Strategic background

In 1779, the British Crown was attempting to put down the rebellion of its American colonies. The familiar history of the American Revolution emphasizes formal battles between the British and American armies such as Breed’s Hill, Brandywine, Saratoga and Yorktown. But west of the Alleghenies, a lesser-known and less conventional war alternately smoldered and flared, in which all sides, British-Loyalist, American and Native, visited destruction and terror on the other’s settlements and villages.

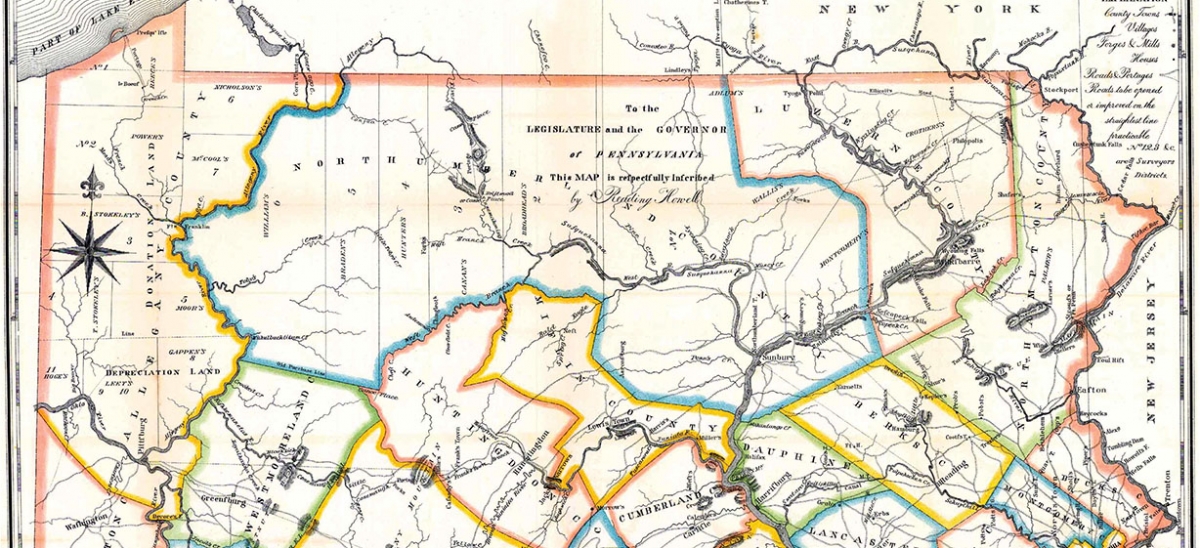

Both British and Americans coveted alliance with the powerful Iroquois League, a confederation of six Native nations whose homeland stretched across central New York into northwestern Pennsylvania . Alliance with Native forces was a potent advantage in frontier warfare as Washington had learned well through his French and Indian War service to the king of England 25 years earlier. When most Iroquois, including the westernmost Seneca, took the British side and began raiding frontier settlements, aided and encouraged by Loyalist militia, Washington devised a strategic response. He ordered Gen. John Sullivan with 3,000 men to advance up the Susquehanna River, while Gen. James Clinton with a smaller force struck west from New York’s Mohawk Valley. Sullivan was to meet Clinton and, with their combined force, march west across the Iroquois heartland (which he did), burning the Indians’ towns and destroying crops and stored provisions. The objective was to crush the Iroquois inclination and ability to help the British oppose the American cause.

By spring 1779, Col . Brodhead, who had been with Washington at Valley Forge two winters before, had assumed command of Fort Pitt, far from consequential battles in the Revolution’s eastern theater. His main concerns at Fort Pitt were the logistical challenge of provisioning a wilderness outpost and defending scattered Ohio Country settlements from Indian attack.

Initially, Washington’s plan to send generals Sullivan and Clinton against the eastern Iroquois had a western component. Brodhead would lead whatever forces he could raise up the Allegheny to strike the Seneca, while also diverting Indian and Loyalist attention from Sullivan’s advance. Washington’s letters indicate he viewed Fort Pitt’s commander as a capable officer, but Brodhead’s correspondence suggests that, stationed at Fort Pitt, he felt underutilized in the war effort. He welcomed the assignment to lead an expedition against the Seneca, the most formidable branch of the Iroquois League. But in May, Washington changed his mind and cancelled Brodhead’s mission, fearful that it would be difficult to maintain a supply line so far into enemy lands and that it would leave settlers around Fort Pitt exposed.

Brodhead, though, was determined. He continued to gather recruits and supplies while exhorting Washington to authorize his campaign. In mid-July, Washington relented, informing Brodhead by letter of his “consent to an expedition against the Mingoes (Seneca).”

Brodhead’s modest army, assembled mostly from the 8th Pennsylvania and 9th Virginia militias, marched out of Fort Pitt on Aug. 11, 1779. His report to Washington states that he commanded 605 “rank & file, including militia & volunteers.” The column headed north on foot while its supplies were poled upriver in boats beyond presentday Kittanning. From there, with provisions lashed on 400 pack horses, they marched north across a forested plateau that is now Clarion County to short-cut the westward bend the Allegheny takes below Tionesta (known then as Cushcushing). At Tionesta, they crossed to the Allegheny’s west bank and continued upstream toward a cluster of Seneca towns above Canawago, where Warren, Pa., stands today.

Encounter and clash

Somewhere near today’s Tidioute, Brodhead deployed an advance guard “consisting of 15 white men including the spies and eight Delaware Indians.” Farther upriver on Aug. 18 or 19, the paths of Brodhead’s forward scouts crossed that of the Seneca paddlers. Muskets flashed and blood flowed. That much, from all accounts, is known.

Brodhead’s report, dated Sept. 16, told Washington that his advance guard “discovered between 30 and 40 warriors coming down the Allegheny River in seven canoes.”

Brodhead then relates that the Indians “immediately landed, stript [sic] off their shirts and prepared for action, and the advance guard immediately began the attack,” followed by reference to his preparing the main body to “receive the enemy” and then Brodhead’s own move forward where, as he told Washington, he found the Seneca in retreat, leaving behind canoes, guns, shirts, blankets, blood trails from the wounded and five dead.

His force fared better. According to Brodhead’s letter: “Only two of my men and one of the Delaware Indians were wounded and so slightly that they are already recovered and fit for action.”

Return to Fort Pitt

Brodhead continued upriver to deserted Canawa go, where he recalled that “the troops seemed much mortified because we had no person to serve as a guide to the upper towns.” The column followed signs of retreating Indians to the vicinity of where Salamanca, N.Y., is today. After remaining “on the ground three whole days destroying the towns and cornfields, ” Brodhead turned his troops and marched back down the Allegheny.

Bearing farther west on his return, Brodhead sent a detachment up French Creek when they reached Venango (Franklin, Pa.), which razed another abandoned Seneca town and destroyed more crops. After the army’s main body had marched through 320 miles of western wilderness, while its flankers and detachments had covered as much as 406 miles, the expedition returned to Fort Pitt on Sept. 14 without losing a single man or pack animal, according to Brodhead’s statement.

Battlefield search and an alternate view

During 2015, Commonwealth Heritage Group examined all previous reconstructions of Brodhead’s route and evaluated surviving oral history among the Seneca. In October, a team scoured the best battlefield location candidate with sophisticated metal-detectors, seeking musket balls, bayonets or other 18th-century martial implements.

“This event shows how messy history can be.”

—Keith Heinrich, Pa. state historic preservation specialist

“We pulled together all the accounts looking for consistencies,” said Chris Espenshade, military archaeologist and Commonwealth Heritage Group’s project leader, now employed at Skelly and Loy, Inc. in Pittsburgh. “We have descriptions of landforms and general distances from known points. We know canoeing behavior and the kinds of places people tend to pull over to shore.

“The details we culled made us focus on one location, but the archaeology didn’t say one way or another,” Espenshade continued. “Had there been formal lines of battle with more participants, a lot of items would have been dropped. We did find four artifacts, but nothing conclusively definitive of battle. This fight was so fleeting and brief; any surviving signature is likely to be very light. Still, we’re confident we were in the right place.”

To protect the site from exploitation, conditions of the National Park Service grant prohibit Espenshade from divulging the location he suspected and searched. The location will, however, be published in his report to be circulated among the project partners for review.

“Then we’ll redact the final report document, taking out any mention of the landowner and identifying photographs,” Espenshade said. “This is standard policy in the Battlefield Protection Program. That said, our general findings about the expedition will stay intact.”

Regarding location, Espenshade points out that the battle’s acquired name may be misleading.

“There is a string of islands along that stretch of river, one of which today is known as Thompson’s Island, but it never had that name until a hundred years after the battle,” Espenshade explained. “And it’s possible there was confusion even then because there is a different island at the mouth of Thompson Run.”

The incident’s elusive location and enigmatic name are not its only aspects that remain unclear, even open to question. Espenshade’s analysis leads him to believe there were fewer Seneca involved than Brodhead reported and that they were, at the time, more interested in hunting deer than battling enemies of their British allies.

“It is my interpretation that, at the time of this encounter, the Indians were not prepared for a fight, while the Continentals were,” Espenshade said at a September public meeting in Warren. “Perhaps the key question is: Was The Battle of Thompson’s Island really a battle in the classic sense?”

That question aligns with what Seneca accounts have long told.

“The history that’s been written regarding Brodhead’s march has been one-sided,” said Jay Toth, tribal archaeologist of the Seneca Nation of Indians. “The Seneca oral versions were known, but never taken into account. Our people have always said this was a hunting party, not a war party, and in the moments before what’s known as The Battle of Thompson’s Island, they were camped with their canoes beached and were surprised in some way.”

There is a secondhand written account of the encounter in the Revolutionary War memoirs of Blacksnake, a Seneca chief who recorded it as told to him by Redeyes, a Seneca who claimed to be present. Blacksnake relates there were “about 10 of them (Seneca) together following downstream on the Allegenny River with bark canoes and hunting furs, Redeyes and his comrates was down about five miles below Brokenstraw. They had been campout [sic] on the bank of the river.”

“I tend to put value on oral history coming from people whose families lived there at the time this happened,” Espenshade said.

Espenshade, who cautions that his interpretation does not necessarily reflect that of project partners, believes Brodhead felt motivated to present the results of his expedition to Washington in the best possible light.

“Brodhead had argued vehemently to Washington that his mission was needed,” Espenshade said. “It’s a better narrative for him if they came across a war party than a hunting party. It doesn’t have the same power to justify the expedition if they stumbled on Indians around a campfire.”

Espenshade points to Brodhead’s assertion that he did not lose a single man or pack animal as further cause to question his report.

“I find it hard to believe, even if we didn’t have conflicting oral history, that anyone could take that many people that far at that time, and not even lose a horse,” Espenshade observed. “Oral history holds that the Seneca attacked farther upriver and as many as seven of Brodhead’s men were killed. If that happened, it’s understandable that he did not report it. He wanted to convey a perfect expedition.”

The Seneca Nation of Indians has directed Jay Toth to apply to the National Park Service for a separate Battlefield Protection Program grant to search for evidence of those upstream engagements.

“Brodhead wanted a glowing report for Washington, and he knew the other side wasn’t going to be able to hold him accountable for what he wrote,” Toth said.

Aftermath

Washington later promoted Brodhead to the rank of Brigadier General. After the Revolution, Brodhead served in the Pennsylvania General Assembly and as Pennsylvania’s Surveyor- General, a career that would not have been hindered by a self-congratulatory depiction of his campaign against the Seneca.

Despite the American Revolution’s ultimate outcome, Espenshade proposes that the overall military success of Washington’s pincer attack on the Iroquois homeland, including Brodhead’s expedition, is questionable.

“The Seneca were disrupted, temporarily refugees, and forced to seek aid from the British that winter. But they came out of this with a sense of revenge,” Espenshade said. “It’s hard to term this a great success when you look at their raids on the frontier in 1780. Washington and the Continental Army did not win the war in the west, but they won the rest of it and that was enough.”

The Battle of Thompson’s Island, then, remains an intriguing if poorly documented and misunderstood event, marginal to the wider scope of the American Revolution. Still, it evokes compelling human struggles within this region, where 18th century war west of the settled coastal plain was brutal, complex and capricious, and where the stakes for all involved were high.

“It’s good that we are now fleshing out a deeper understanding,” said Keith Heinrich, historic preservation specialist with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission’s State Historic Preservation Office. “This event shows how messy history can be.”

“People died there along the Allegheny. It’s hallowed ground,” Toth reflected. “These incidents have been forgotten on a national scale and even locally. It’s right and important that we gain the most accurate understanding possible for ourselves, and to convey to future generations.”