The RSVP: An Art Lost?

Many years ago, when Sam Menefee was a student at Oxford, he would arrange to meet a friend for dinner by leaving a handwritten note in the pigeonhole, or mailbox, of his friend. The friend would respond by leaving a note in Sam’s pigeonhole.

The charming and humorous notes were part of a wonderful tradition that continued due to thoughtfulness, a finely honed English sense of etiquette and the unfortunate absence of telephones from students’ rooms.

As circumstances and technologies have changed, however, behavior and etiquette have evolved accordingly. Just as we find the world inhabited by the characters in Jane Austen’s novels to be charming, but in some ways quaint and archaic (people writing letters and waiting days or weeks for a response), so do many of our traditional customs and manners seem to be hopelessly slow, inefficient and outdated. In a world where people communicate almost instantaneously by cell phone, e-mail and text messaging, is there still a role for written invitations, responses to invitations and thank-you notes?

In the past, an invitation usually was an act of generosity, an attempt to include someone, or to get to know someone better. An invitation focused on the relationship much more than the transaction of an actual event, for example, a lunch or dinner. In 2006, the reverse is often the case. Two friends might do something together, or they might not. It depends on whether they have scheduling conflicts and if they both feel like getting together at that particular moment.

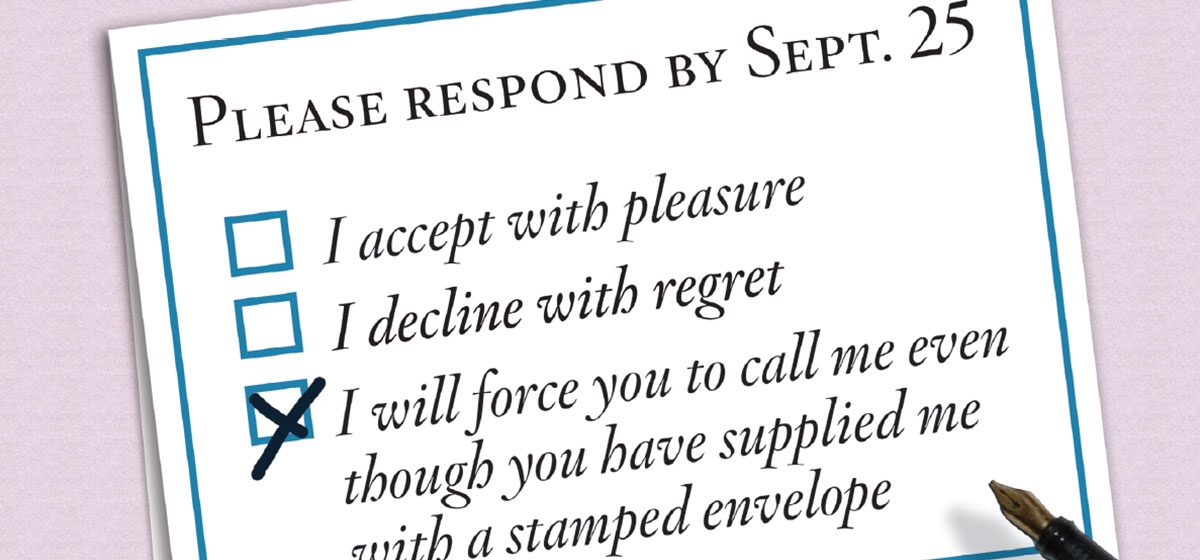

People are less and less willing to commit to plans or to other people ahead of time. Arts organizations find patrons are more reluctant to subscribe to season tickets. Nobody wants to commit to a date in the distant future when so many unexpected things can happen in the interim.

Often, perceived etiquette transgressions arise from tensions between people living in entirely different worlds. One senior executive and his wife received an invitation to a dinner party being held by friends six weeks later. When they didn’t respond within a week, he received a call from his prominent hostess. She was going to Europe for four weeks and needed to know if the executive and his wife were going to come. She wanted to have her seating arrangements completed, so she wouldn’t have to worry about them during her trip. The executive said he hadn’t yet decided whether he would be in Pittsburgh, Washington, New York or London on the evening in question. He told the hostess that he and his wife probably should decline, given the uncertainty of his schedule. When the hostess persisted, the executive replied that he would love to attend if in town, but that there was only a 50 percent chance. The best he could muster was a definite maybe. The irresistible force had met the immovable object.

Some views of etiquette appear to vary by sex. When a friend was getting married in 2005, virtually all of her friends (most of whom are female) promptly sent back the enclosed reply card in response to her wedding invitation. They understood how important the cards were to planning events surrounding a wedding. The cards are useful to the hosts (or, more accurately, to the hostesses) not only for a head count but also for seating arrangements and making certain all guests’ names are spelled correctly.

Three weeks before the wedding, only four of her fiancé’s friends (all of whom are male) had sent in reply cards. When her fiancé made a round of calls to his friends, one replied, “I already told you that I’ll be there for you, but my wife can’t make it. Why do you need the stupid, little card?”

The director of development of a major, local cultural institution said that R.S.V.P. response rates to invitations to parties or events are dropping. The same number of people attend events, but they are more reluctant to commit ahead of time.

One popular couple offers an explanation. If you receive three invitations a day, you can respond to each. If you receive 10 or 15 a day, you can’t. This couple differentiates between personal invitations from close friends and institutional invitations sent to hundreds or thousands of people. They believe invitations from close friends deserve a prompt response. On the other hand, they answer institutional invitations only if they’re interested.

A similar phenomenon is occurring in our day-to-day communications. If you receive five telephone calls and five e-mail messages a day, you can respond personally to each. If you receive 100 phone calls and 400 e-mails a day, you have to make choices. And so, with many who don’t respond or always seem to respond slowly, it may not at all be the case that they’re lazy or thoughtless. They may be overwhelmed.

Manners and etiquette take on greater significance when the people we encounter every day take to the road. You can choose your dinner guests. However, you can’t choose with whom you share the road. And even nice people often become monsters behind the wheel. One friend described an unexpected encounter with one of her friends, a small woman driving a large sport utility vehicle. As they both emerged from the parking lot of a certain upscale supermarket, her friend glared directly at her and then quickly cut her off as they each attempted to leave the lot. “People think they don a magic cloak of anonymity when they step into their cars. They think no one will recognize them, and they behave accordingly.” The friendship never has been quite the same.

In the 1980s, two men argued over a Shadyside parking space. When they couldn’t agree, one pulled out a gun and killed the other. In the early 1990s in southern California, driving habits changed dramatically after 10 well-publicized freeway road-rage shootings. “I have never seen drivers in California behaving so courteously,” said management consultant Ed Jenks. “People went out of their way to wave strangers in ahead of them and to allow them to merge. There’s no question about it. An armed society is a polite society.”

Etiquette may be changing most among teenagers. With instant messaging, teens get to know each other electronically in a way that, for better or worse, avoids the awkwardness and body language of face-to-face introductions.

One incoming college freshman looked up her prospective roommates’ e-mail addresses a week before orientation. By the time they actually met, they were close buddies from numerous heart-to-heart IM sessions.

You must be careful with online communications. What you write can be saved forever or, perhaps worse, forwarded endlessly verbatim. That kind of broadcast breach of etiquette and privacy may only be topped by the danger lurking in a teenager’s home. While blithely typing away your innermost secrets, what could be worse than having your parents come up behind you asking, “What are you doing?”

Parental eavesdropping, either in person or by reading automatically saved IMs, has led to the typed warning “ploms” — “parent looking over my shoulder.”

The saving ploms cause each online conversant to reduce their language and content to PG, the appropriate level for the unseasoned ears of unassuming parents.

Finally, in probably the clearest case of the medium affecting the message, the IM world has created its own language. Pittsburgh Golf Club tennis pro Matt Guyaux reports that a typical text message to arrange a lesson might read: “C U @ 7 2nite.” [“See you at seven tonight.”] It’s a far cry from the mannered witticisms of the Oxford pigeonhole, but if brevity is the soul of wit, we might be witnessing the rise of the wittiest generation in history.