The Weird Inconsistencies of Trust Busting

Last week, I suggested that the enforcement of America’s antitrust laws has made little sense since the Sherman Act was adopted in 1890. In fact, the word that comes to mind is “fiasco.”

Previously in this series: “Making Monopoly Illegal: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part VI”

I mentioned earlier in this series the fact that socialist economies consist of almost nothing but monopolies — state-owned ones. Imagine an entire economy managed as well as the U.S. Post Office.

Clearly, it wouldn’t make sense to organize a free market economy that suffered from the same monopolistic deadweight that bedevils socialist economies just because the monopolies are privately owned. We need some way to prevent anticompetitive practices. But based on the history of U.S. antitrust enforcement to date, we haven’t found the right approach.

What led to the Sherman Act was the shock to the human sensibility that was wrought by the Industrial Revolution. For 250,000 years — since Homo sapiens separated itself from Homo erectus — human industry had been a small and rather intimate thing.

Such making-of-things as there was depended on human, and later animal, and still later water-power, and those activities tended to take place inside or around individual homes or farms and to be performed by individual craftsmen.

Then, quite suddenly, in the late eighteenth century, everything changed. The new ability to harness much more powerful sources of energy (steam and internal combustion engines) allowed work to move out of homes and into coal mines, steelworks, and auto and textile factories, and also allowed manufacturing to operate on a vastly larger scale.

People migrated in huge numbers from small farms and villages to increasingly large and crowded cities to work in these new factories and the conditions they worked in seemed positively appalling (cf., Dickens). In fact, of course, no one forced people to leave their rural areas and take these new jobs. People did it because, however hellish the mines and mills seemed to be, they were preferable to the medieval conditions of farm life.

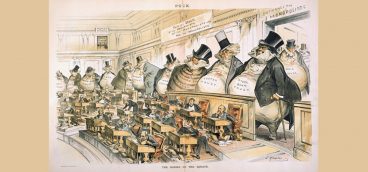

Still, no one had ever imagined, much less seen, industry on the scale of the United States Steel Corporation, Ford Motor Co., or Standard Oil. The sheer size and power of these corporations, and the men who ran them, was flat-out terrifying.

State governments were no match for these new entities, and even the great federal government in Washington seemed paralyzed, if not actually impotent, in the face of the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Mellons, Morgans and so many others. People weren’t used to seeing such behemoths, and of course governments themselves were much smaller back then. Hence, the Sherman Act.

The trustbusters and muckrakers went to work and Standard Oil was broken up into the so-called “Seven Sisters” oil companies (Gulf, Texaco, Shell, etc.). Trusts were also broken up in the tobacco, meatpacking and other industries.

But careful economic studies of the era showed that industries characterized by trusts (collusion) had brought prices down considerably faster than prices had fallen in supposedly more “competitive” industries. Standard Oil had dramatically reduced the cost of refining, for example, and that was what its competitors were complaining about.

Aside from oil, in the decade before Sherman the price of pig iron fell 21 percent, sugar 22 percent and copper 10 percent. Certainly there were other reasons for going after the trusts, but the main concern had been that consumers were being abused by unnecessarily high pricing, which turned out to be false.

Moreover, there seemed to be little rhyme or reason to which firms the government targeted or which firms it would be successful in reigning in. As noted, Standard Oil was broken up, but U.S. Steel, a far larger and more powerful company, was not. Ford was ignored entirely.

Indeed, looking back at the early days of antitrust enforcement, it is hard to conclude anything other than that the government was targeting successful companies for little reason other than that they had been successful.

For example, in the (ultimately unsuccessful) antitrust action against International Harvester, the District Court held, as described by the U.S. Supreme Court:

“[A]lthough it was not shown that there had been any unfair or unjust treatment by the International Company [sic] of its competitors and there was nothing in the history of its expanding lines which should be condemned, it had been, from its beginning, [a violation of the Sherman Act].”

The courts had tended to strike down antitrust prosecutions based merely on size or success, but the government kept bringing them anyway. During the so-called Progressive Era (roughly 1896 to 1916), the trustbusters busted trusts with gleeful abandon.

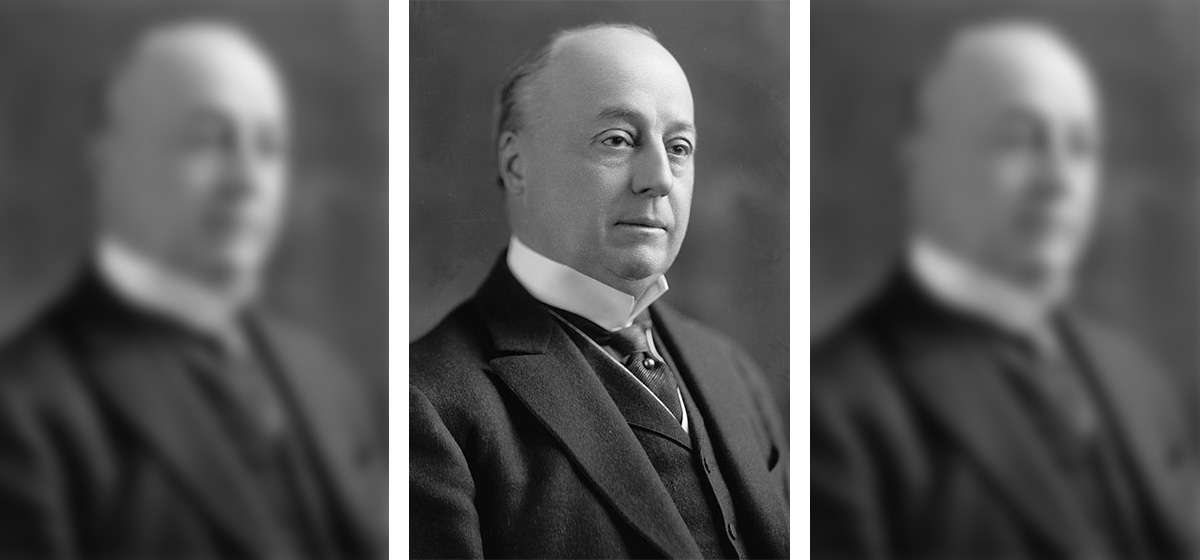

Bizarrely, one of the most enthusiastic of the trustbusters was U.S. Attorney General Philander C. Knox. I say “bizarrely” because Knox was the cofounder of the law firm I would eventually join, 97 years later. In 1877, Knox and James H. Reed formed Knox & Reed (the original name of Reed Smith), which, the day it was founded, was one of the most powerful law firms in the world.

Knox was a highly influential man in America. He’d served as a U.S. Attorney and a two-term U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania, and, later, he would serve as U.S. Secretary of State. In-between, he was Teddy Roosevelt’s Attorney General.

Reed, meanwhile was the personal attorney to Andrew Mellon. Knox & Reed advised, in addition to Mellon, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, H.J. Heinz, Alcoa, U.S. Steel, and many others. And yet, once in harness as Attorney General, Knox filed more than 40 antitrust actions against companies across almost every industry in America.

Again, looking back on it, these prosecutions look suspiciously like collusions between the government and the second most powerful firm in an industry. I don’t mean they were collusions, just that the end result was the same.

The government would go after the most powerful firm, which would weaken that firm whether the prosecution was ultimately successful or not. The number two firm in the industry would then step up to be number one, putting itself in the government’s crosshairs.

It was a silly game of Whack-A-Mole, in which the government’s own actions created the moles. Revulsion against this nonsense led to a collapse of interest in bringing antitrust actions after the Taft Administration. Indeed, during FDR’s Administration, efforts were actually made to limit competition (the National Industrial Recovery Act, for example).

Which brings us to the current era, which has seen its own fair share of antitrust debacles, as we’ll see next week.

Next in this series: “Government Missteps: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part VIII”