The Waning Mao-Xi Dynasty

“Without democracy, China will rise no farther.” —Jiwei Ci, University of Hong Kong

The history of China is long and violent and, more than anything else, it is an endless story of history repeating itself. Dynasty follows dynasty, beginning in 1250 BC with the Shang Dynasty and ending with the Mao-Xi Dynasty, which is still in power.

Every dynasty arises in violence, by defeating its predecessor dynasty in battle. There then follows a period of years—often, many years—during which the victorious dynasty attempts to consolidate its power. Typically, this means battling with warlords and strongmen across China until all opposition has been crushed.

But nearly as often it means contending with powerful non-Chinese peoples, with the result that many “Chinese” dynasties have actually been governed by non-Chinese conquerors. For example, the Later Tang, Jin and Han Dynasties were ruled by Shatuo Turks, the Yuan Dynasty was ruled by Mongols (its first emperor was a grandson of Genghis Khan), and the Qing Dynasty was ruled by the Manchu.

If all goes well, the new dynasty will rise to wondrous heights, sometimes lasting nearly a millennium (the Zhou, 1046 BC to 256 BC) or producing a golden age of prosperity and culture (the Tang, AD 618–907, and the Song, AD 960 to 1127).

But all rarely goes well, and in any event even the successful dynasties eventually fall victim to the fate of the weakest dynasties. In other words, as is the case with all autocratic societies, successful and unsuccessful dynasties enter a negative cycle characterized by:

Increasing corruption, as powerful factions jockey for power and confiscate state assets for their personal use.

Increasing social unrest, as corruption and poor, autocratic governance cause the populace to become restive.

Increasing tyranny, as the threatened dynasty becomes ever more repressive.

Increasing weakness, as corruption, the need to repress a restive populace, and the need to guard vast borders against invasion all combine to exhaust the regime.

Eventually, the people revolt—often aided by regional warlords—or an invading army descends on the dynasty’s capital. The dynasty falls, a new dynasty arises, and the cycle begins all over again.

The Mao-Xi Dynasty has followed this inexorable path exactly:

Mao’s forces defeated the Kuomintang in 1949, establishing the first half of the Mao-Xi Dynasty.

The new dynasty spent three decades consolidating its power, with Great Leaps Forward following Great Leaps Forward (the first one alone killing 45 million people), and as Cultural Revolution followed Cultural Revolution (with millions more dying).

With China on the verge of collapse and cultural suicide, Deng Xiaoping purged Mao’s successors (including Mao’s own wife) and launched long-overdue reforms, leading to a brief golden age.

Deng’s reforms eased Mao’s tyrannical governance and introduced formerly despised capitalistic practices, resulting in vastly accelerated economic growth and prosperity.

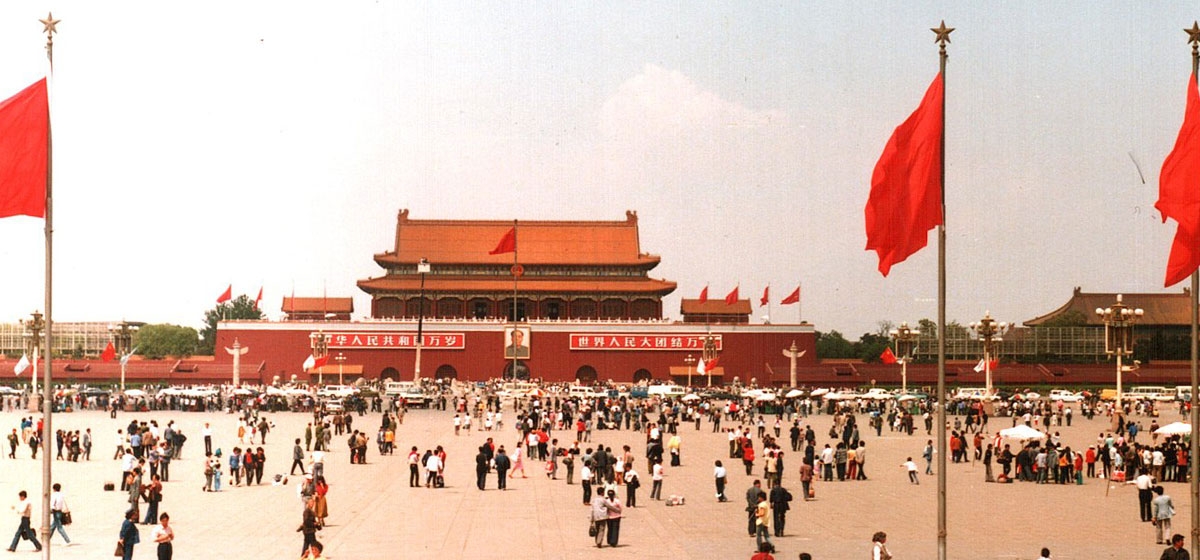

All went well until 1989, when thousands of Chinese citizens began demonstrating in Tiananmen Square, demanding faster reform, including free speech and democratic elections.

Terrified by the demonstrations and the widespread support the demonstrators were receiving across China, Deng and his cronies elected to crush the demonstrations, murdering more than 1,000 people.

Thereafter, the dynasty became increasingly corrupt, as Communist bosses jockeyed for power and confiscated state assets for their personal use.

The corruption and, especially during Xi’s reign, increasingly autocratic governance caused social unrest, especially in outlying regions and in Hong Kong.

The Mao-Xi’s dynasty became ever more repressive in an attempt to crush opposition to the dynasty’s leadership.

By the early twenty-first century the Mao-Xi Dynasty, desperately trying to control a restive population, was spending more on internal security than on external defense.

Eventually, the people of Hong Kong revolted, presenting the Mao-Xi Dynasty with a problem we might describe as Tiananmen Square-squared.

We know that Deng and the Central Committee were terrified by the Tiananmen Square demonstrations – one million people were in the square at the peak and several hundred million additional Chinese were cheering the demonstrators on. The Chinese leaders were also deeply divided about what to do.

Ultimately, of course, Deng chose to crush the demonstration at a cost of at least 1,000 lives. You might suppose that a country that committed such an act would become an international pariah, and that’s what Beijing feared most.

But the West turned a blind eye. Tiananmen Square, it was said, was merely an unfortunate hiccup on the long road to Chinese convergence with the West. And barely more than a decade later China was admitted to the World Trade Organization. China’s economy exploded and the West’s manufacturing economy was hollowed out. Talk about a home run for Beijing!

It was all reminiscent of nothing so much as the spring of 1936 when, on the early morning of March 7, Adolph Hitler sent 30,000 heavily armed German soldiers into the demilitarized Rhineland. Hitler’s action was an egregious violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Pact, and Hitler himself was terrified, fearing a powerful response by France and Britain.

In 1936 Hitler knew he wasn’t strong enough to stand against France or Britain, let alone both. If either nation had reacted strongly—moving troops to the Rhine, for example—Hitler would have had to execute a humiliating retreat, with who-knows-what consequences for him and his party. But France and Britain looked the other way, and the result, three years later, was the most destructive war in the history of the species.

The world looked the other way after Tiananmen Square, too, and Beijing prospered mightily. But this time around Beijing is unlikely to get away with murder. Instead, as we’ll see next week, the Hong Kong unrest marks the beginning of the end of the Mao-Xi Dynasty.