The Value of Living Separately

We’ve talked a lot about De Rarum Natura, but we haven’t actually experienced the poem in these pages. There’s a reason for that—poor Lucretius has been unlucky in his translators.

The vast majority of the DRN translations have been made by Latin scholars. These renderings are technically accurate and have the merit of passing along the substance of the work. Unfortunately, the majesty of the language got left on the cutting room floor.

There are a few translations by poets – especially Thomas Gray (see below) – but these tend to suffer from the opposite defect: the language is beguiling but the substance is lacking. The first English translation, by the way, was produced by a woman, Lucy Hutchinson, in the 1650s but the manuscript was never published and was later renounced by Lucy. It was finally published in 1996(!) Gray’s poetical translation was probably the best, but unfortunately most of it has been lost.

Still, let’s take a brief look at the poem itself, to see what it’s like.

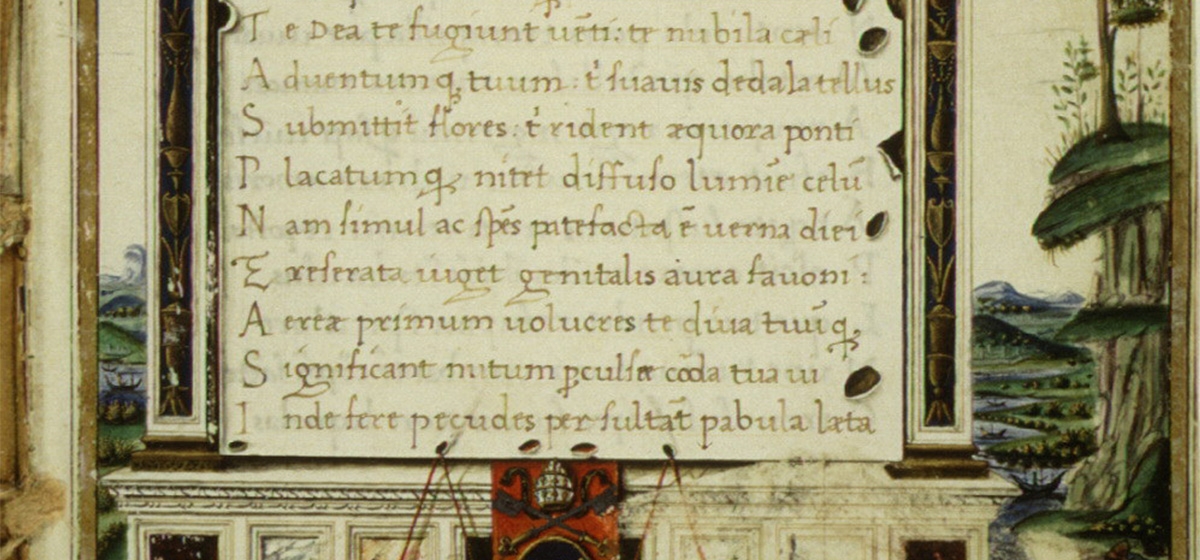

De Rarum Natura opens buoyantly on the first day of spring with a prayer to Venus to partner with Lucretius on the work. Spring, of course, is the vernal equinox, the date when the sun passes the equator en route north. But in the latitudes of Athens and Rome it was also a date with a much more practical significance: it signaled the first day that fields could be tilled. Herewith the opening of the poem (quotes are from Sir Ronald Melville’s translation for Oxford University Press unless otherwise noted):

“O mother of the Roman race … great crop-bearer … at your coming/The winds and clouds of heaven flee all away … You I desire as partner in my verses/Which I try to fashion on the nature of things.”

7,400 lines later the poem ends with a harrowing description of the plague that struck Athens in the fifth century BC. Lucretius’s description of the plague is precisely accurate but, to say the least, hard to read:

“First were their heads inflamed with burning heat

And the two eyes all glowing red and bloodshot.

Then throats turned black inside sweated with blood,

And swelling ulcers blocked the voice’s path…

… the breath roiled out a noisome stench

Like that of rotting corpses lying unburied;

The neck all sodden with a shining sweat;

A small thin spittle, yellowish and salt,

And upward from the feet by slow degrees

Cold crept on.”

In true Epicurean fashion, Lucretius pokes fun at our fear of death and the odd ceremonies we attach to it:

“… when in life he tells himself his future

That after death his body by wild beasts

And birds will be devoured, torn to pieces,

He’s pitying himself.

… For if in death

It is painful to be mangled by wild beasts

I do not see how it is not also painful

Laid on a pyre to shrivel in hot flames

Or to be crushed under a weight of earth.”

But Lucretius can also speak quite tenderly about death, asking us in effect to experience the crushing sadness of death before overcoming the emotion through philosophical contemplation. The following lines were translated by Thomas Gray and incorporated by him in his “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard:”

“For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire’s return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.”

Before we say goodbye to De Rarum Natura, let’s briefly ask ourselves how a person like Lucretius could possibly have happened. No other ancient saw so far in so many ways, or set down his extraordinary ideas so magnificently. Yet he was, in the first century BCE, a nobody, his entire life having made no ripple on the public scene of the Roman Republic. He would be forgotten for 15 centuries.

We know, from the evidence of the poem, that Lucretius received a first-rate classical education. We was fluent in both Latin and Greek and had obviously studied Plato, Hippocrates, Homer, Ennius, Heraclitus, Anaxagoras, Empedocles and many other Greek and Latin luminaries. In addition, of course, to his philosophical father, Epicurus.

We also know that Lucretius was intimately familiar with the terrible events in Rome that persisted throughout his lifetime. The first century BCE saw the final collapse of the Roman Republic – it died a mere decade after Lucretius died – and the launch of the Roman Empire under Augustus. It was a period marked by foreign wars, civil wars, street fighting and ugly political trials.

So here we have a man who took the best education Rome had to offer, who knew in detail what was happening in his country, yet whose life was spent entirely outside the mainstream of Roman society. Lucretius lived and wrote in the countryside, probably on a Lucretia family estate, and was in close correspondence with almost no one. His lifetime spanned only 44 years. And yet he was one of the most consequential people who ever lived.

We’re all familiar with Isaac Newton’s remark that “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Newton meant that all discoveries are incremental and based on earlier works of genius. (Nietzsche, however, maintained that most scholars merely reduce the work of earlier geniuses to their own myopic level.)

In any event, Lucretius had a different idea. He believed that our ability to see and understand is impeded by the very people around us. We mostly live very public and/or social lives, surrounded by friends, colleagues, acquaintances. Without realizing it, our own thoughts become circumscribed by the prejudices, opinions, factions and ridicule of those we interact with. That is to say, our ability to see to the far horizon is blocked by the very crowd we are a part of.

But not Lucretius. He thought and wrote as the freest of men, able to speculate about life and nature in an extraordinarily autonomous way. This highly intelligent, well-educated man distanced himself from his contemporaries, communing mainly with the ancient greats and a few close friends. It’s a useful object lesson for those of us with impossibly busy social and professional lives, hounded by a 24/7 news cycle and omnipresent social media.

Which reminds us that there is one other remarkable thing about Lucretius – there will never be another like him.