The Trouble With Rousseau

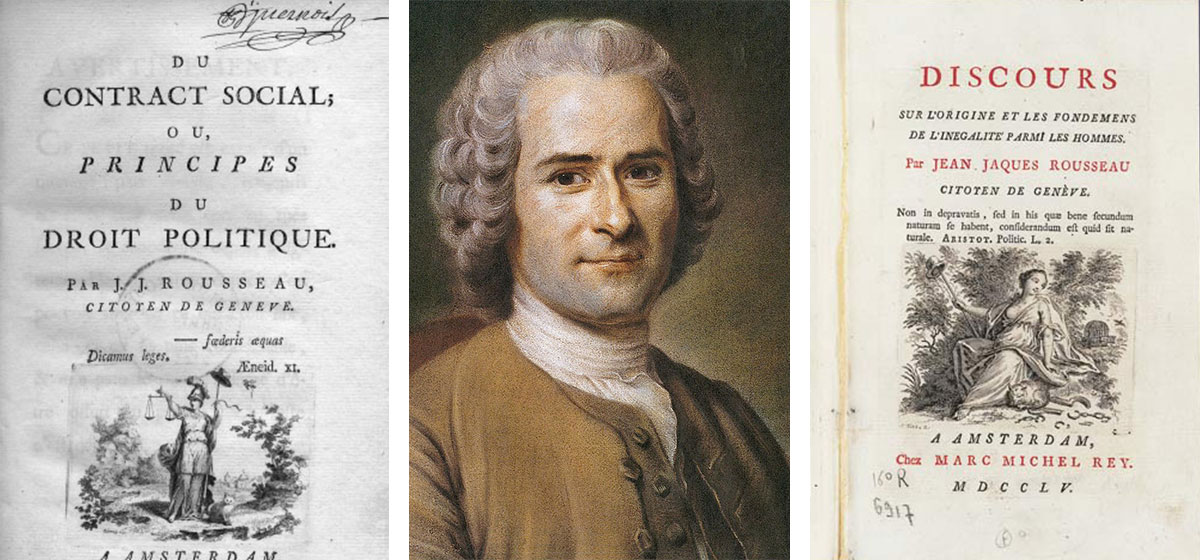

“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” —The first line of Rousseau’s “The Social Contract”

Even by the loose standards of his era, Jean-Jacques Rousseau lived a bizarre life.

Rousseau’s mother died giving birth to him and he was mostly raised until his teen years by an uncle. At that point, his care was given over to an aristocratic woman, Françoise-Louise de Warens, who oversaw his education and also took Rousseau as her lover. Since she was also intimate with her steward, Rousseau’s first sexual experience was as part of a ménage à trois.

The ever-thoughtful Madame de Warens secured a plum job for Rousseau with the French Ambassador in Vienna, but Rousseau was bored and quit, lighting out for Paris. There he entered into an affair with a seamstress named Thérèse Levasseur, who bore him at least two and, possibly, five children, all of whom were placed in orphanages.

While in Paris, Rousseau entered an essay contest on the subject, “Have the arts and sciences contributed to the moral improvement of mankind?” Rousseau’s answer (“No”) so impressed King Louis XV that the king offered Rousseau a pension. Rousseau promptly turned it down.

In 1761 Rousseau’s novel, “Julie, ou La Nouvelle Héloïse,” electrified Europe, purportedly causing readers to swoon, suffer seizures and sigh interminably. If you observed a fellow stumbling down the Champs Élysées sobbing uncontrollably, you could be sure he had been reading “Julie.”

Rousseau’s first books on philosophy provoked such outrage that he was banned from France (and Switzerland) and had to take refuge in England. There he entered into a towering and famous feud with David Hume and ended up taking as hasty a leave of England as he’d taken from France.

Like his Anglo-Saxon counterparts, Rousseau in his philosophical works tried to imagine what the lives of men and women must have been like in a “state of nature,” why governments formed, and which kinds of governments were legitimate or illegitimate. But Rousseau’s conclusions were diametrically opposite to those reached by Hobbes, Locke, Hume et al.

For Rousseau, mankind was only happy in a state of nature. Once governments began to be formed, people quickly became miserable, for the simple reason that governments were nothing more than a contrivance by which the strong imposed their will on the weak. (Hence the quote that launched today’s post.)

Rousseau didn’t explain why it was that the strong in a state of nature, unfettered by government power, weren’t free to impose their will on the weak, but whatever.

In books such as “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men,” “The Social Contract,” and “Emile, or On Education,” Rousseau pounded away on the notion that no known government could do other than enslave its citizens, no known form of government could do other than to make its citizens unhappy.

Rousseau acknowledged that the social contract, as understood by Hobbes, Locke, Hume et al., and as embodied in the title of Rousseau’s second book on political philosophy, was an accurate description of the unspoken agreement between governments and citizens. As the Anglo-Saxon thinkers had outlined it, individuals surrendered certain rights to governments in return for protection and the preservation of other rights.

But while the Anglo-Saxons saw this tradeoff as acceptable, and, therefore, certain governments (that is, liberal democratic ones) as legitimate, Rousseau saw the social contract as a bad bargain. Central to Rousseau’s concerns about the world’s governments was his belief that people are almost infinitely malleable, that “The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable [that is, negative] change in man.”

The only way for people to return to the happy state they enjoyed before governments formed, according to Rousseau, was to overthrow the existing social contract—that is, to overthrow all existing governments—and to replace them with a new social contract based on direct popular sovereignty.

But Rousseau also believed that human beings weren’t yet ready to govern themselves—men and women had been so corrupted by governments that popular sovereignty could not safely happen until an enlightened leader (Rousseau’s infamous “Legislator”) arose to change people sufficiently that they could be trusted to govern themselves.

There were two very radical implications of Rousseau’s political theories. The first was that no government, including liberal democracy, was legitimate, and therefore, citizens were free to revolt and overturn any government in the world. Needless to say, this didn’t endear Rousseau to the reigning governments of the day.

The second, and perhaps more ultimately destructive implication, was that, since mankind was happiest during a state of nature, the main duty of a government was to “improve” its citizens, to take them out of their current misery and mold them into happier versions of themselves. These new, improved people could thereafter govern themselves satisfactorily.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that both the French and Russian revolutions grew out of the first of these implications, and that out of the second grew the Terror in France and the horrors of Marxism-Leninism in Russia.

I have elsewhere in these pages described the well-meaning but ultimately tragic determination of European governments between World War I and World War II to “improve” their citizens (e.g., here), that is, to create a “New Man” who would be superior in every way to the existing human population.

The horrific consequences of Rousseauian political theory eventually led virtually all European countries to move toward the Anglo-Saxon model, although old habits are hard to change.

All this isn’t, however, to suggest that liberal democracy has all the answers. In fact, it is the apparent cluelessness of liberal democracy in the face of the key issues that matter today that suggests that liberal democracy may have passed its expiration date.

Next week, we’ll look at what is perhaps the most challenging issue contemporary liberal democracies face: equality.