The Secret to Finding Morels

“I can’t seem to give ’em up

I just like morels too much

I like other ’shrooms and such

But I just like morels too much

Oyster mushrooms mighty fine

Seafood and some nice white wine

Chanterelles’re tasty too

In a wild mushroom ragout

Storebought shrooms can be a crutch

but I just like morels too much”

—from the song “I Just Like Morels Too Much,” words and music by Zoe Wood, Fungal Boogie Lyrics

When we moved to the farm 30 years ago, I knew what trespassers carrying guns were doing on our property, but not those carrying brown paper bags. Entire families meandered through our woods, chatting as they went, heads bending toward the ground, their eyes scanning decayed leaves and the green growth of spring. They kneeled, put something in those bags, and walked on. My mail carrier told me: They were searching for morels.

She’d hunted mushrooms for 45 years and knew a good spot on our property, which she divulged, but said most people go to their graves before revealing a favorite patch. “It’s guarded like a tomb,” she said. Once, in our woods, she filled two shopping bags full of morels, then ran home in heavy rain before the bag broke. I’ve never had such luck, but have stalked the edible fungi ever since.

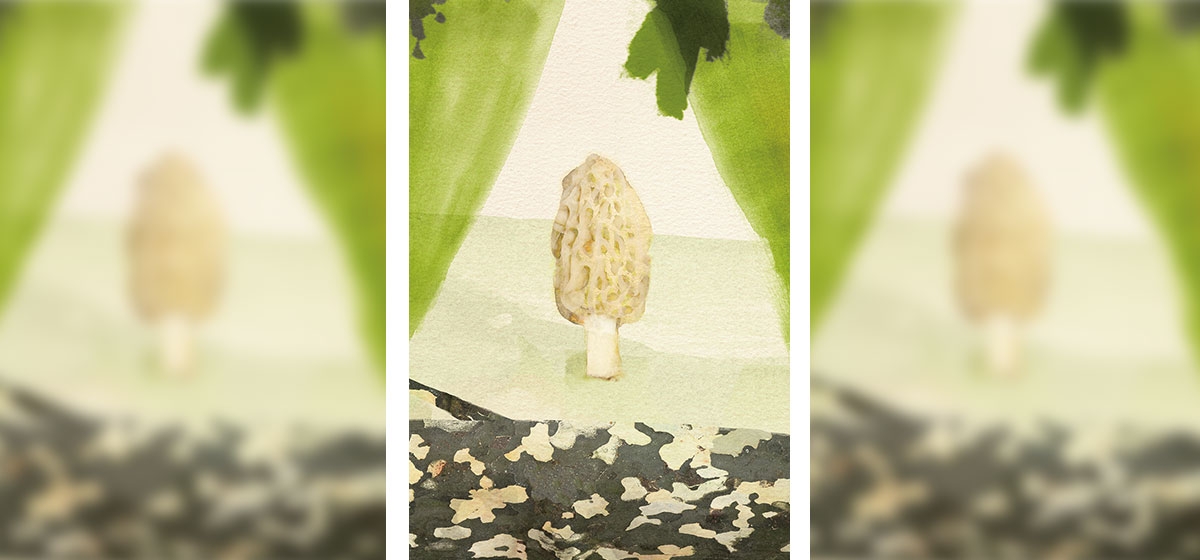

A morel doesn’t look like your typical toadstool. Instead, its cap—found in shades of yellow, white, grey, beige, and black—is conical in shape with pits and ridges resembling honeycomb, or sponge. The stalk is whitish and hollow. The black morel (Morchella elata) is the first to emerge in spring, and Bob Sleigh, club identifier of the Western Pennsylvania Mushroom Club, found his earliest on St. Patrick’s Day—though he has legendary status in the club, finding morels when no one else can. The yellow morel (Morchella esculenta) appears two or three weeks later, according to Michael Kuo, author of the book, “Morels.”

Mushroom lore is rampant in our western Pennsylvania hills, and locals have theories about when and how to find them. After the first warm rain, when crocus are in bloom, or when tulip leaves are the size of squirrels’ ears. They swear by their favorite haunts: old apple orchards, under ash or tulip trees, by dying elms, and near rotting logs. Mine is the tulip, but Mr. Sleigh said that’s because it’s the most common tree in our area to support morel growth. (The truth is, morels can be found on the edge of driveways, in lawns, garden beds, or shopping center mulch, but that’s hardly sporting!) In the western U.S., morels sprout after forest fires, and even in the east, Mr. Sleigh advised looking under trees hit by lightning. And it’s the end of the season that produces the biggest mushrooms, according to Mr. Sleigh—his record is 14 inches—which he’s found under sycamores. Morel hunters use a myriad of nicknames not found in my mushroom guide: rubbernecks, longnecker, bigfoot, brainies, Christmas trees, butter sponge and giant, among others. A friend swore her brother-in-law could smell them, which has always made me wonder if I might train our dogs to find them, like pigs with truffles.

April and May is the general season, but it’s not predictable. Mr. Sleigh has known morel season to last as long as six to eight weeks, and as short as one. Some people wait until tax day to go out, but if so they may miss them all, he said. He gave me a trick: Take the daytime temperature, add it to the nighttime temperature, divide by two, and when that number equals 50, it’s time to head into the woods. That’s because morels begin to fruit when ground temperature reaches 50 degrees. He follows web groups too, which trace morel sightings from Georgia northward in spring. One thing he said is “gospel”: Start the season on a south facing slope, and work your way around the mountain as the days warm up.

Morels are not easy to find. I look for shape, texture and color, but am often fooled by half-eaten walnut shells, acorns and the yellow-brown squawroot. (Squawroot signals the season’s end, Mr. Sleigh said.) Kneel down, he suggested, and look uphill; children are particularly good at finding mushrooms because they’re so low to the ground. Then turn around, and see what you missed. A rule of thumb is: Where there’s one, there’s another nearby.

I was told years ago to carry a mesh bag so mushroom spores could scatter as I wandered, and I do so diligently, but Mr. Sleigh said mushrooms produce millions of spores, and the few that fall don’t really matter. Mr. Kuo agreed. “The use of mesh bags is based on fundamental misunderstandings about how morels reproduce and how spores act,” he said.

Still, Mr. Sleigh said mesh bags are good for air circulation— which prevents mushrooms from rotting—and to enable dirt and bugs to fall off. Don’t carry them in plastic. To pick a morel, I was also told never to pull out the root, but he plucks the entire mushroom, cuts off the bottom and buries it in another spot—so no one knows exactly where he found it. “It’s a competitive hobby,” he said.

One of my local babysitters told me to clean morels in a salty bath, but Mr. Sleigh said, “Never!” The flavor is in the spores, and water washes off those spores, lessening the taste. He slices morels in half lengthwise and whisks them with a soft bristled brush.

For me, one of the great pleasures of mushroom hunting is looking at the nascent world around me as I walk. In early spring, the forest floor is peppered with such wildflowers as trillium, jackin- the pulpit, trout lily, phlox and wild geranium. The birds are back: the eastern towhee sings “Drink-Your-Tea” and bluebirds nest in their boxes again. Skunk cabbage rises in the marsh, watercress lines the stream bank, fiddleheads unfurl, and ramps blanket the hill behind our barn. Other mushrooms pop up too, and I imagine fairies atop them, solving fairy problems. But I don’t pick them; I limit my mushrooming to morels only.

Safe foraging is crucial. In his book, “The Complete Mushroom Hunter,” Gary Lincoff, a Pittsburgh native and author of “National Audubon Society’s Field Guide to North American Mushrooms,” divides people into two camps: mycophiles, those who love mushrooms, and mycophobes, those who fear them. I’m not scared, but I am careful, watching in particular for poisonous false morel, the most common being Gyomitra, with a reddish brown cap resembling a brain, and a stalk stuffed with a cottony substance. Mushroom hunters are advised to study before picking or eating any wild mushroom, and never eat them raw. Join a reputable club, Mr. Sleigh suggested, or hunt with people who know what they’re doing and can teach you. “We want people to be safe,” he said.

I wondered why my mail carrier found so many more morels than I, so I asked Mr. Kuo: “Is it climate change?” That question, he said, is “unanswerable in any scientific way, absent data.” But the morel’s decline is well documented, he went on, and probably corresponds to the decline of the American elm.

When my daughter was 13, she liked to hunt morels with me, fry up in butter the few we found, and eat them on toast. One day we were horseback riding near the spot my mail carrier recommended, and on the edge of the woods we spotted the biggest morel either of us had ever seen. It was huge and golden, and we figured there’d be more, so we trotted down to the barn, un-tacked the horses and put them in the field, and scurried back to the spot. It was late in the morel season, and the mushrooms were hidden under may apples, which covered our harvest like a myriad of tiny umbrellas, right out of a children’s book.

“Found one!”

“Found one!”

We yelled it over and over to each other until we had 33 perfect specimens. Never had we found such a stash. But when we fried them, she didn’t like the toast as much—too morel tasting, she said!

My mail carrier was correct: There is something magical about that spot. But I found only two the following year, and not one in the 10 years since. Perhaps the poachers got there before me.

The Western Pennsylvania Mushroom Club can be found at wpamushroomclub.org.

Michael Kuo’s website is mushroomexpert.com.