The Search for the Lost Archives

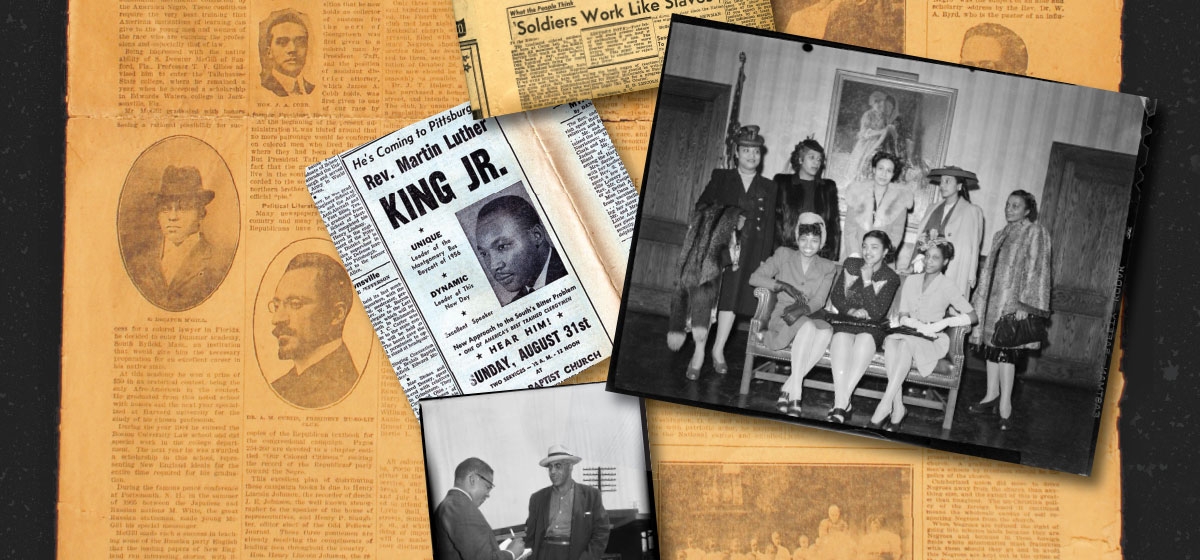

A lifeguard’s strong dark arms buoy his young, light-skinned pupil, as other children in the pool cheer their friend’s attempts to swim. The undated, black-and-white photo from the archives of the Pittsburgh Courier is part of a century-long storyline about the lives of African Americans that the newspaper chronicled.

It is also part of a collection that documents the bigger story of race relations in Pittsburgh and beyond.

The complexity of this photograph, however, pales compared with the intricacies of the archive to which it belongs. The Courier was founded in 1910 and by the 1930s was the nation’s most prominent weekly newspaper for African Americans. For nearly the past four decades, however, many believed its archive had been lost to history. People loyal to the Courier’s founders were convinced that what remained of the archive had been left in the wrong hands following a prolonged court battle between the bankrupt newspaper and the Chicago-based publishing family that took over the drowning paper’s debt and launched the New Pittsburgh Courier in 1966. And now some fear that the archive’s future in Pittsburgh remains uncertain.

The dumpster

Those around during the Courier’s 1966 bankruptcy recall the dumpsters filled with old photos, story clips and other documents that were trashed when the newspaper vacated its building on Centre Avenue, in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Routine “throw outs” preceding the bankruptcy prompted area residents to offer security guards a few bucks for the chance to jump into the bins and grab keepsakes before the contents were carted off to the landfill.

“My photo collection was what [neighbor Tommy Tondee] gave me, and what he gave me came from that dumpster,” said John Brewer, a Pittsburgh native and local historian. “I probably have 5,000 to 7,000 photos thanks to him.”

Brewer said those who got jobs at the New Pittsburgh Courier couldn’t recall much about what transferred over to the new offices on East Carson Street, despite a contract agreement that gave the bankrupt newspaper’s intellectual property to its new owners.

Over time, younger generations of journalists replaced the old guard. They didn’t know as much about the paper or its legendary Double Victory campaign of the 1940s that sought freedom from oppression for all people, both at home and abroad.

They had little knowledge of the newspaper’s legacy or of the men and women who became legends, such as Robert L. Vann, who laid the foundation for the Courier’s success; Mrs. Jessie Vann, who, after her husband’s death, expanded the business into 21 American city editions and a circulation of more than a million readers; P.L. Prattis, the editor who launched the Double V campaign; Frank Bolden, the first African American to gain military press credentials during World War II; and Charles “Teenie” Harris, the paper’s famed photographer, whose keen eye documented everyday black life.

It was into this environment that Brewer made a cold phone call to the newspaper’s offices in the summer of 2005. He explained to the woman answering the phone that he was working with the Carnegie Museum on identifying images taken by Harris and asked whether they had any of his pictures.

“[She] told me that they pretty much threw that stuff away when the old plant shut down,” Brewer said. “As a historian, I was very disappointed to hear this, but wasn’t surprised, because I had heard similar stories from historians in Harrisburg, who told me they had written the Courier off completely.”

Brewer, however, had a hunch. So he hopped in his car and drove toward the New Courier’s South Side office. “I got to the Homewood Cemetery and my car conked out. It just died,” Brewer recalled. “I got out of the car and was standing there, looking across the street.”

That’s when his eyes fixed on a solitary marble mausoleum towering over the cemetery.

Etched in stone, it read: Robert L. Vann. “I got back into my car and it started right up. I was spooked out.” Brewer saw the inexplicable incident as a sign to continue his pursuit of the old archives.

When he arrived at the New Courier’s offices, a staff member ushered him to a dimly lit closet door and offered a dismissive comment about slim chances of finding anything. Instead, Brewer discovered a large, 18-foot deep and five-foot wide closet lined with shelves from floor to ceiling and crammed full of boxes.

“I climbed up the ladder and there, lined up in neat rows, was the whole photo archive. All there since 1966,” Brewer said. His legs shook. He climbed back down, a hand filled with photographs that hadn’t seen sunlight in decades. He quickly called colleagues at the Carnegie Museum of Art and asked them to come authenticate the find.

Then he sat down and flipped through the stack of images, feeling as if the voices of those who had walked before him were calling out through time. There were grisly compositions of corpses hanging from trees; frightened faces of the Scottsboro, Ala., boys; famous musicians making stops in town; and couples dancing.

“My heart was racing,” Brewer said. “It was a mystical experience.”

About the time he started hyperventilating, Kerin Shellenbarger arrived, and the photo archivist for the Teenie Harris Archives at the Carnegie Museum was equally surprised. “We believed this myth that there was nothing left,” said Shellenbarger. “All the outsiders thought this stuff was gone. Whereas, the Courier staff knew it was there, they probably just didn’t know what they had.”

After a rudimentary survey, Shellenbarger and Brewer estimated the collection contained about 800,000 photos alone, including prints obtained through Associated Press and UPI wire services, the Department of Defense during World War II, and publicity shots sent prior to visits by celebrities.

“The actual amount of unique material is half or a third [of that number],” Shellenbarger said. “And that’s really a rough estimate.”

Brewer said a $150,000 federal grant the paper received to archive the material will cover a small fraction of the cost to properly preserve it for future generations.

Historic treasure

Six years later, Brewer equates finding the archives to an archeologist finding the Holy Grail.

“What’s kind of surprising is that even [African Americans] don’t know about this history,” said Patrick Washburn, a professor in the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University and an expert on the black press. “The history they have been told is largely a white history. Yes, they know about Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Booker T. Washington. They know about a few of the famous individuals, but not much before the Civil Rights Movement. It’s like black history doesn’t exist before the Civil Rights Movement.”

The most striking thing about the Courier archives is the breadth and depth of black experience they contain, said Laurence Glasco, associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh. “Even though people are perhaps more aware of that experience today, it often gets reduced to poverty… When you read the pages of the Courier, and the range of topics it covered, you get education, lodges and sororities, the Hill House, the schools, the ports, churches, cartoons, literature. It really shows what a rich and varied community existence there was.”

Washburn contends that the archives of black newspapers are among the few places where African Americans can learn the truth about themselves and the role past generations played in American history. “It’s not only important for blacks, but it’s important for whites. Especially when you start adding in what happened to blacks in our country, you start to get a fuller history, a true history of the way this country developed.”

Washburn noted that outside of black newspapers, the only way people of color appeared in the mainstream press was if they were sports stars, talented entertainers, or arrested.

“Unless you fell into one of those three categories, it was impossible to appear in white newspapers. White papers didn’t talk about blacks who died or blacks who were born, or blacks who were married, or blacks who advanced in business… In many ways, the white press made the black papers successful because black newspapers were providing news that black readers couldn’t get anywhere else.”

That began to change in the 1960s, Washburn said, as television captured images of police officers blasting civil rights protesters with water hoses or letting K-9 dogs loose on peaceful marchers. Stories about African Americans could no longer be ignored and began appearing on the front pages of mainstream newspapers, from Pittsburgh to New York City. Not surprisingly, black press circulation slid.

Mystery solved

Decreasing readership became a problem for the old Courier.

Letters from Executive Editor P.L. Prattis revealed years of financial turmoil leading up to Mrs. Vann’s Oct. 15, 1966 sale of the Courier to John H. Sengstacke, owner of the Chicago Defender and the Michigan Chronicle. In a Nov. 26, 1950 letter, Prattis wrote about Mrs. Vann’s discussing the selling of her share. “I don’t think she wants to do so. She has been reluctant when conditions were good because such a sale would seem to represent failure. Another reason is that she has not been able to think of Negroes in legitimate businesses who would have the money. I think that she might think she was betraying a trust to sell the business to whites. That would seem to represent another kind of failure.”

At one point, Mrs. Vann found serious financial backers in nearby Uniontown.

“I became her lawyer when a substantial offer for the paper had come in by a white person,” said retired Pittsburgh attorney Wendell Freeland, who worked for Mrs. Vann until her death. “But I concluded that what this guy wanted was complete control and the agreement would give him that. When Mrs. Vann wasn’t willing to give complete [editorial] control, he backed away from the offer.”

Freeland said Mrs. Vann refused to sell to someone who would change the paper’s social advocacy. She held out until 1966, when on the brink of bankruptcy herself, she agreed to sell to Sengstacke for $1, according to rediscovered court documents.

In exchange, the Chicago-based newspaper chain—which also owned the Courier’s chief competitor the Defender—agreed to take on the struggling paper’s $1 million debt, pay the IRS some $100,000 in back taxes, and share a portion of its initial profit with the old newspaper.

It was a sale that some in Pittsburgh’s African-American community did not welcome.

“Some people are venomous in their hatred of Mr. Sengstacke,” said Rod Doss, current publisher of the New Pittsburgh Courier. Doss blamed the hatred on “profound ignorance” by people who had no idea who Sengstacke was or what he stood for, adding that many heard the surname and automatically made assumptions.

“The other aspect of that is you were dealing with John H. Sengstacke, who was a very astute businessman. He was counseling with some of the best attorneys in the country and he had them working on his behalf,” Doss said. “And there were a lot of people in the city, who I do recall… thought he was white. Again, ignorance.”

Doss argues that many loyal to the old Courier also had financial axes to grind; some owned stock from the old newspaper that was rendered useless.

“So you were dealing with a lot of different things. People who just wouldn’t let go or thought that they still had a stake or a claim to whatever was going on with the new publication.”

Court documents of the original sales agreement show the Courier changed its name to Pittsburgh Liquidating Corp. and offered the New Pittsburgh Courier its intellectual properties, including the old archive. The old building on Centre Avenue was padlocked and sold to repay the IRS.

It was during this time that Richard Jones, a prominent Pittsburgh attorney, former NAACP president, and friend of the Vanns, was named receiver in the Courier’s bankruptcy proceedings. As such, he had to make sure the New Pittsburgh Courier made good on its promise. Nearly 10 years after the sale—and without seeing a cent of profit—Jones took the New Pittsburgh Courier to court, prompting a decade-long battle that concluded in 1983, with the New Courier paying $10,000 as part of a settlement agreement that named it the rightful owner of the old Courier’s archives and other intellectual property.

Jones died three months later.

“If anyone could keep a secret, he could,” said Rose E. Scott, Jones’s only child, who now lives in Arkansas. Scott said she wasn’t surprised her father took knowledge of the settlement to his grave. Even Jones’s closest work associates knew little of the decade-long legal battle.

“[Richard] was angry. He didn’t like what was happening,” said Freeland, who was Jones’s former law partner. He recalled Jones’s choice words for the Chicago competitors—“rotten sons of bitches”—who were negotiating to continue the Courier’s legacy.

“You have to keep in mind that the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier competed very, very heavily with each other,” said historian Washburn. “For Courier readers and employees… it was not so much a blow that Mrs. Vann sold, but definitely a blow because of who she sold to.”

The feeling persists.

“Sengstacke wanted the advertising. He didn’t care about the paper; he didn’t care about the Courier’s legacy,” said Nancy Bolden, whose late husband, Frank, was a long-time Courier employee. “My only issue, really, is they are two different newspapers. And frankly, to say ‘We are the continuation of a paper that had 20 editions and 400,000 weekly subscribers,’ to say that ‘We are that paper,’ is insulting.”

Doss, however, disagreed.

“John Sengstacke respected the Courier and its legacy and its history. I think he was once quoted as saying it would be a shame to have a newspaper as strong as the Courier disappear.”

Preserving history

It was the desire to share this rich history that drove Ken Love, a Pittsburgh-based documentary filmmaker, to capture several key reporters and editors on camera in his 2009 film, “Newspaper of Record: The Pittsburgh Courier.”

“This is American history, not just black history. And the Pittsburgh Courier has not gotten the credit it deserves for all its work on the campaigns that made America a better place,” said Love. “That paper was heroic and Pittsburgh should be proud of it. Here you have this archive that by whatever accident was saved. This is cause to celebrate.”

Local historians and academics agree the Courier’s archive should remain intact, be available to the public, and stay in Pittsburgh.

“[This is] one of our most valuable archives nationally and internationally,” said Pitt’s Glasco. “No community is better documented than Pittsburgh’s black community in any place in the world.”

Shellenbarger at the Carnegie Museum concurred: “Keeping [the archives] in Pittsburgh would be essential. It really completes all the photo collections in the city, both black and white. It should stay here. It’s Pittsburgh.”

Doss noted that the New Courier’s current parent company, Real Time Media LLC, has begun the expensive process of digitizing the old newspapers and many of the key photos unearthed by Brewer. “You share it as best you can,” said Doss. “I don’t see anything untoward happening [to the archive]. We are in the process right now of cataloging, digitizing and creating a permanent record so that those things don’t happen.”

He noted that it was the New Courier’s contracting with ProQuest, a company that specializes in digital archiving, that prompted Real Time Media to begin making digital copies of other historic black newspapers in its ownership.

Doss said subscribers can buy online access to old copies of the Courier, essentially recreating coverage on any given topic or date.

“Having it available online has opened up The Courier to all kinds of research for undergraduates and graduate students as well as academics,” said Glasco. “These are topics you couldn’t explore in this sort of detail before.”

But he notes that the research is limited to the print product. There are currently no mechanisms in place to search through old newspaper images, and the earliest years of The Courier are missing.

Other experts argue that digitizing the archives isn’t the same as opening the original material up to researchers. Washburn contends that a searchable archive in Pittsburgh would draw historians to the city.

Doss, however, said Real Time has given him no indication of plans to work with area archivists, opting instead to maintain the archives at the East Carson Street offices. “They are also looking at how they may be able to take some of the historical photographs and, either through arrangement or with Getty images, be able to dispense them [digitally] or sell them online.”

Washburn said he understands the need for newspapers to make profits, but also notes the Chicago Defender set a precedent when it gave its historical archive to a Chicago-area library for archiving a few years ago. “It means the archive will be used a lot more than if it is not archived. It means that the paper… will be written about a lot more by historians.”

He said un-archived materials discourage research, which in turn limits the reach of sharing the publication’s story with a wider audience. “I think they are making a tremendous mistake,” Washburn said. “The reality is, the more researchers use that material, the more the story will get out, the more researchers and scholars will know. Given the historical importance of the Pittsburgh Courier,

I think it is important that that stuff is available and easy to use.”