The Rich Will Lose Their Money Soon Enough

We are talking about Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” including its extraordinary publishing history and its subsequent fade from grace. I reviewed the various problems with Pikkety’s theses as they have been noted in the economics literature, and I also proposed my own view of the book’s central problem: that its author is a naïf.

Two of Piketty’s naïve errors, discussed last week, include mistaking a truism for a “fundamental law” of capitalism, and failing to account for the very large costs people with capital to invest almost always incur.

This week we’ll focus on the worst of Piketty’s errors: Naïve error #3: Ignoring risk.

Let’s refer back to the early nineteenth century, the era of Jane Austen’s novels and the starting point for Piketty’s argument that wealthy people over very long periods of time can easily earn 4% or 5% on the value of their capital—in this case landholdings. As I pointed out last week, if those people were able to achieve such returns, they did it only by overcoming serious costs. But, more importantly, nobody gets 5% net except by exposing their capital to very significant risk.

Some of those risks are idiosyncratic. In Austen’s time, land was passed down from generation to generation, almost always following the rules of primogeniture, via which the land went to the eldest son. How long would it be before such a system produced a complete ne’er-do-well as the heir?

Some families lucked out, of course. Consider Sir Edward Phelips, Master of the Rolls under Elizabeth I and, not so incidentally, the prosecutor during the trial of the Gunpowder Plotters (including Guy Fawkes) who intended to blow up the House of Lords. Sir Edward was knighted for his service to the crown, and he built a large country house called Montacute, in which his descendants resided for 400 years. (Alas, the end came in the early twentieth century when the family finally ran out of money.)

Far more commonly, though, only a few generations would go by before an incompetent eldest son—or his inattentive trustee—would badly mismanage the family’s land. Farmers and tenant farmers would abuse the soil, over-planting and over-grazing, wearing out the land for generations and impoverishing the family. Or a dishonest steward would rob the family blind. Poof—the capital was gone.

Other risks affected land owners generally. Consider very bad weather, leading to poor harvests. A well-managed nineteenth century estate would have maintained a cushion of capital just for such exigencies, but more poorly managed families would be wiped out. Even well-managed estates were unlikely to survive several years of bad weather in a row.

But there were much worse risks just over the horizon. In the mid-nineteenth century British agriculture was the envy of the world. But a few thousand miles to the west the U.S. Congress was passing the Homestead Act (in the midst of the American Civil War, of all things), which awarded people free land in the American Midwest if they would agree to farm it. More than 1.5 million people took Congress up on its offer and American farm production soared.

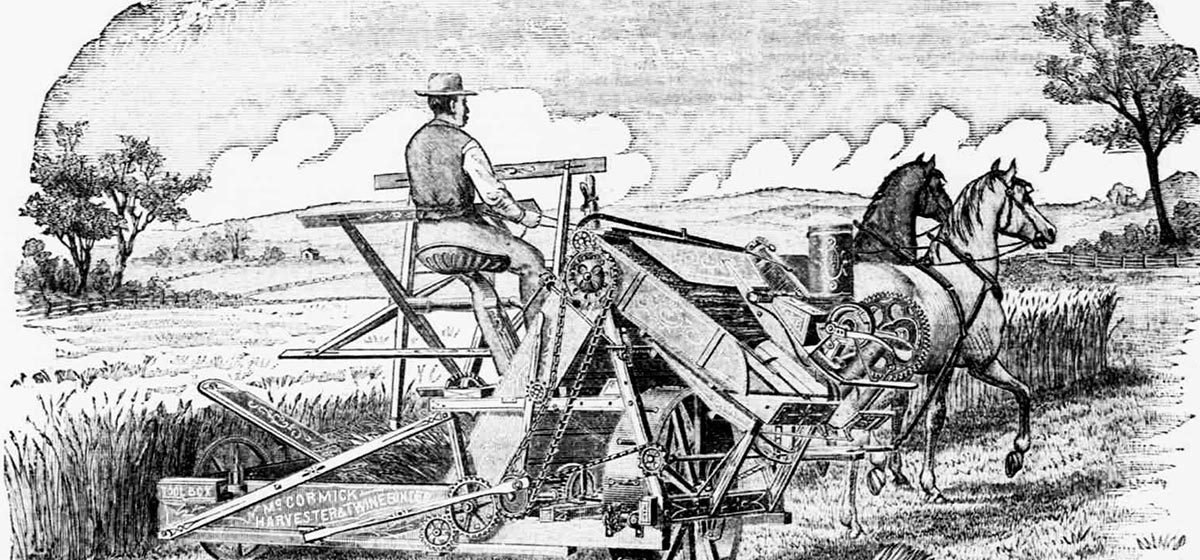

To make matters worse—if you were trying to compete with the vast American agricultural machine—smart entrepreneurs were inventing much more efficient ways to farm, including, of course, Mr. John Deere’s famous steel plough. Other entrepreneurs were reinventing the transportation infrastructure necessary to get American farm products to their markets, including railroads and steamships.

The result was that Britain was soon flooded with huge quantities of cheap American grain and meat, driving prices down in Britain far below anything the landed gentry could compete with. The Great Depression of British Agriculture began in 1873 and prices continued to fall until 1896, lasting more than twice as long as America’s Great Depression of the 1930s. Farm production in Britain wouldn’t reach its 1872 level until after World War II, 80 years later.

The Agricultural Depression decimated the aristocracy and the landed gentry in Britain. “Burke’s Landed Gentry,” a peerage that began publishing in the 1830s and that required a family to own at least 500 acres to be included, fell on hard times. “Burke’s” was forced to keep reducing the amount of acreage required for inclusion, eventually settling on 200 acres.

Then it got worse. The Great Agricultural Depression was followed by the devastation of World War I and the high taxation of the next few decades, further undermining whatever was left of the gentry. By 1972 a family could be included in “Burke’s” even if they were penniless, as long as their ancestors had been landowners.

In their prime, the British aristocracy and landed gentry were known as “the 10,000,” i.e., the 10,000 wealthiest families in Britain. Suppose each of those families had no more than £20,000 each—roughly $50,000 American dollars at the time. If Piketty’s analysis were correct and the families could simply compound their wealth at 5% infinitum, there would be, today, 200 years later, tens of thousands of billionaires in the UK. ($50,000 compounded at 5% for 200 years is worth almost exactly $1 billion.)

In fact, how many billionaires are there in Britain in early 2018? Precisely 54. And not a single one of them is related to the (formerly) wealthy landed gentry, and not a single one of them made their money on farmland. And 200 years hence, how many of the descendants of the 54 billionaires will still be wealthy? Zero. Far from the rich getting ever richer and hogging all the wealth in the world, wealth gets recycled every half century: shirtsleeves-to-shirtsleeves in three generations.

Piketty’s theory that, thanks to r > g, once a family becomes rich they will forever become richer and richer, is exactly the opposite of how the real world actually works. He would know this if he had ever tried to invest capital, had ever known a multigenerational wealthy family, had ever pulled himself away from his econometric models far enough to come up for air and look around at the real world.

Piketty wants to create a society in which people can still become rich by doing useful things, but also in which that wealth will then be taxed into oblivion so that that the children and grandchildren—to say nothing of more remote descendants—won’t be rich. As I’ve tried to show, he needn’t bother—the rich are perfectly capable of becoming poor again all by themselves. More importantly, Piketty and his supporters massively misapprehend the real value of private capital. We’ll look at that issue next week.

Next up: On r > g, Part IV