The Red-Tape Fed

The long and deep recession of 1930–33 finally ended in March of 1933. Once it ended, the Fed, believing that the economy could now—and should now—fend for itself, backed off. The result was one of the most powerful economic expansions in U.S. history, an expansion that lasted three decades.

The short and shallow recession of 2008–09 ended in June of 2009, and once it ended, the Fed, believing that the U.S. economy was incapable of surviving without the help of the Masters of the Universe—excuse me, the Fed—doubled down, imposing QE1, QE2, QE3, etc. Only after they finally stopped this foolishness (i.e., just recently) did the U.S. economy finally begin to grow its way out of its Fed-imposed stupor.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s the U.S. economy grew 40%, while the stock market grew hardly at all. The high on the Dow in 1929 (381.17) wasn’t reached again until November 23, 1954, when the Dow closed at 382.74. What the Fed cared about 80 years ago was the economy, which affected everyone, not the stock market, which affected mainly the affluent.

During the Great Contraction of the 21st century the U.S. economy grew 37%, while the stock market grew 88%. I.e., on October 9, 2007, the Dow closed at 14,164.43, and then peaked in January 2018 at 26,616.71. What the Fed cares about these days is the capital markets, which affect the elite, not the economy, which affects everyone.

Which economy would you prefer to live in?

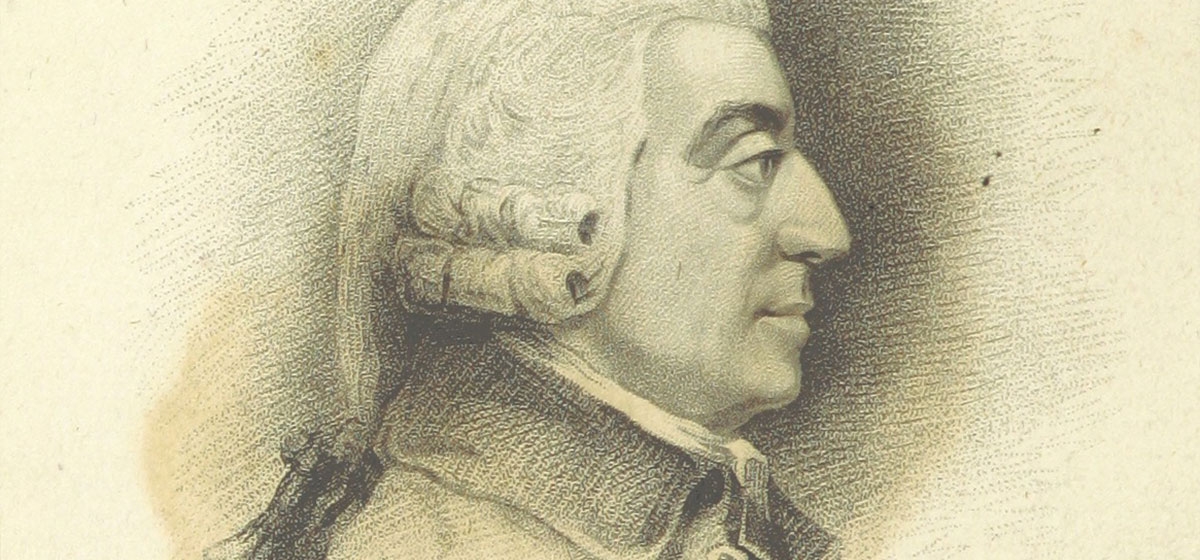

I pointed out in my last post that our central bankers, virtually all of whom went to MIT, skipped the course on Free Markets 101 so that they could take Econometrics, Dynamic Optimization, and Government Regulation. So let’s have a short refresher, starting with the greatest economist who ever lived and who isn’t read any more except by non-economists: Adam Smith.

About the only thing most people remember about Smith is his theory of an “invisible hand” that guides free market economies. When Smith actually used the term “invisible hand” he was using it in a different context—investing in domestic versus foreign economies—but that’s a quibble. We know what Smith meant: each of us, pursuing our own interests, creates economic value for the entire society.

Smith knew perfectly well that the invisible hand wasn’t perfect, but he also knew that it was so powerful, so fundamentally crucial to the wellbeing of citizens, that it should be interfered with only as absolutely necessary.

In Smith’s day the economy of Great Britain was, as Jesse Norman has put it, “beset by thickets of guild, church and state regulation, jealously enforced by insiders with privileged access to government.” Smith recognized that injecting competition into this sterile little world would allow wealth and wellbeing to grow exponentially.

We all know, as Smith knew, that free markets aren’t untarnished. Businesses busy competing with each other sometimes pollute the environment more than they should (viz, coal, steel). Some people and companies don’t play fair (viz., Enron). Company executives sometimes look out more for their own interests as agents than they do for our interests as their principals (viz, publicly held companies). Companies that become very large and powerful sometimes engage in rent-seeking and other anti-competitive activities to protect their dominant positions (viz., Google, Facebook, Amazon).

There is also Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons.” In some circumstances people following their own interests can end up destroying both the public interest and their own. Hardin gives the example of a village where everyone can graze their cows for free on the village common. It’s in each family’s interest to graze as many cows as possible, but the result is that all the grass is eaten up, the cows starve and the people have no milk.

Some of these imperfections, especially the ones that depress effective competition or that seriously affect the public health, need to be circumscribed by laws and regulations. But outside those areas we need to proceed very carefully. Unfortunately, modern economists—and, especially, central bankers—are so aware of free markets’ imperfections that they are perfectly happy to kill the golden goose in order to prevent even the slightest blemish. All too often, the zeal to regulate every possible externality results in a blizzard of red tape that undermines the benefits of the invisible hand and converts competitive, free economies into inefficient, government-managed bureaucracies.

Following the Financial Crisis, the Fed’s instinct was to regulate the hell out of everything so that another crisis couldn’t possibly happen. With Dodd-Frank, they largely succeeded in imposing their will on the U.S. financial sector, with the result that lending could hardly take place and the economy slowly asphyxiated. During the Obama years the regulators had every other sector of the economy in their sights as well.

The regulators weren’t precisely wrong—there were and always will be imperfections in how private economic actors behave. It’s just that in the Fed’s case there was no appreciation for the importance of the invisible hand, for the power of a free market economy to right itself and resume its historical level of growth.

All the Fed saw was imperfection everywhere, all of it desperately in need of their mastery. The result was, as I’ve pointed out, nearly a decade of Fed-induced secular stagnation.

Next week we’ll apply Smith’s invisible hand analysis to the Fed’s actions aimed at the capital markets.

Next up: Central Bankers Then and Now, Part VIII