It was then that began our extensive travels all over the states,” said Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s novel, “Lolita.”

“To any other type of tourist accommodation I soon grew to prefer the Functional Motel—clean, neat, safe nooks, ideal places for sleep, argument, reconciliation, insatiable illicit love.”

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”72″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Poet and fiction writer James Agee ghostwrote a 1934 Fortune magazine article titled “The Great American Roadside,” in which he admired “the oddly excellent fuel of a weak-springed mattress in a clap-board transient shack.” That same year, in Frank Capra’s film, “It Happened One Night,” the unmarried couple of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert spent a rather scandalous night together in a motel. For propriety’s sake, Gable strung a blanket across their room to divide it (which he called the “walls of Jericho”)—and then, on his side of the blanket, gave a funny commentary on the way in which a man undresses. And no one, of course, needs to be reminded of perhaps the most famous motel of all: The Bates Motel in “Psycho.”

My fascination with motels, however, comes from something neither lusty nor macabre, but, rather, from family fishing trips in the 1960s—five of us jammed into a Vista Cruiser, fly rods and sleeping bags in tow. Sometimes we’d camp, but more often after a long day on the river, we’d park the car in front of a small wooden cookie cutter of a bungalow, and settle in for a cozy night in a motel.

The term “motel” was reportedly coined in 1926 in San Luis Obispo, Calif., a combination of the words “motor” and “hotel,” by a man named Arthur Heineman, who owned the Milestone Mo-tel. Motels were also called motor courts, tourist cabins, auto courts, cottages, cabin courts, and a host of other names, and our very own Lincoln Highway, otherwise known as Route 30, had lots of them. After all, if one were driving on America’s first coast-to-coast highway—originally spanning 13 states and running 3,389 miles, from Times Square in New York City to San Francisco—one needed a place to stay. Why, Humbert Humbert might have even stayed in a motel on the Lincoln Highway: “I would take a bed-and-cot or a twin-bed cabin, a prison cell of paradise, with yellow window shades pulled down to create a morning illusion of Venice and sunshine when actually it was Pennsylvania and rain.”

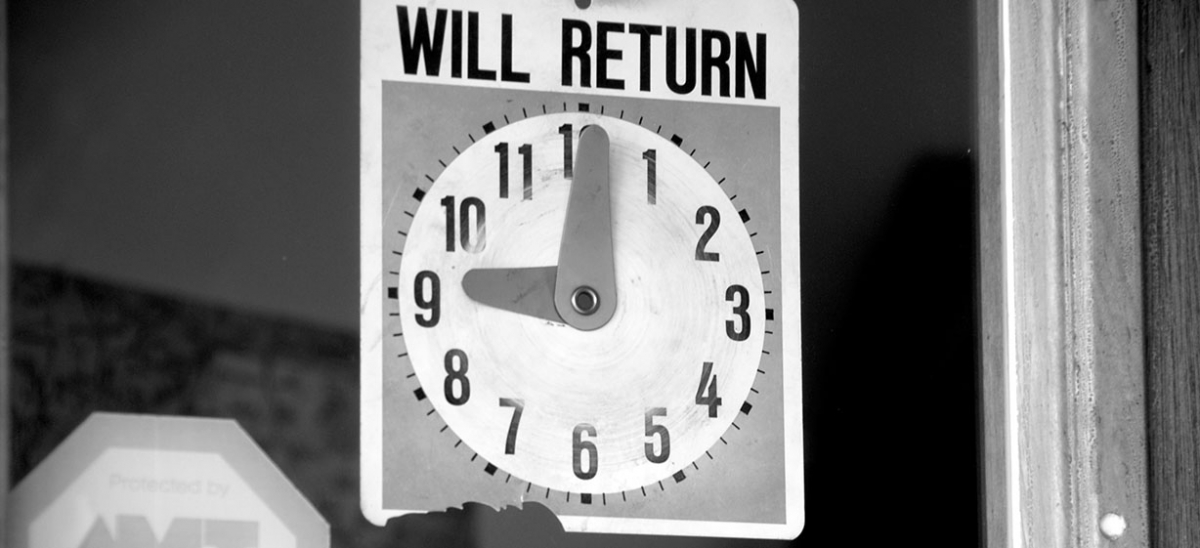

Conceived by entrepreneur Carl Fisher, who helped start the Indianapolis Speedway and built Miami Beach, the Lincoln Highway was opened in 1913. Fisher named it for our 16th president, Abraham Lincoln. And because October 2013 marks the highway’s 100th birthday, I set out to find out what motels were left on my rural end of the famous road. With camera in hand, I was on the lookout for those funky signs, the iconic architecture, the aluminum chairs, the no-vacancy signs, and the smoky corner offices.

Unfortunately, not much remains. In this day of Marriotts and Hiltons and Hampton Inns, the little guys have been forced out. Still, with these photographs I pay homage to the motels still standing, with special thanks to those small motel owners who continue a great American tradition. Sadly, though, without some sort of unlikely, massive motel revival, this small slice of Americana will soon be completely extinct.