The Last At-Bat

Early one morning this summer, I was fishing with my friend in northern Michigan. The fog was thick, and Dave asked if I could tell where I was going. I know those waters and predicted that in about 30 seconds a point with a white boathouse would come into view. It did, and we rounded the rocky point and then hugged the shoreline where the visibility was better all the way to our destination.

“The fog is thick today,” I said. “But there are times when you literally can’t make out anything, and despite everything you know, you’re utterly lost.” I told him what my father had said to me once. “Just because you’re lost in a fog doesn’t mean your compass is broken.” I said I didn’t know if Dad had meant it just literally or in a deeper, metaphoric sense. I suspected both. And I started to say “I haven’t been able to ask him for 25 years now.” But I only made it halfway through that sentence before stopping and remaining silent ‘til we reached our spot.

It was 25 years ago, a couple months before our youngest son, Henry, was born, that my mother called with some news. Dad had had a stroke a few years earlier, and Mom said the doctor thought he had a 50 percent chance of living six months. So in late July that year, after Henry recovered from a difficult delivery, I packed our two older children—nearly 2 and 3 1/2—into the car on a Friday afternoon, and we hightailed it down to Cincinnati. I had a date with destiny.

The Gyro father-and-son softball game was that night. Gyro was a club, to which Dad and Granddad and my brother had all belonged. And they still held the annual game at the Nipperts’ farm. And after the game, everyone would have dinner and beers in a barn that had action photos of the Reds during the Big Red Machine era, when the Nipperts owned the team. I’d always been a good athlete, and Dad was proud of that. I’d had a tryout for the Pirates years before and, at 31, this was one thing I could still do for him, hit a couple home runs and make him proud in front of his friends.

I dropped off the kids with Mom and met Dad and Fred, his assistant, at Nipperts’. The game was under way. I thanked Fred and quickly wheeled Dad over the rough field to the makeshift diamond. I parked him where he could see everything but out of harm’s way, and one of the guys recognized me from years earlier and said, “Hey Doug, it’s your turn to bat.” The bases were loaded. Perfect.

I could feel my adrenaline surge as I grabbed a bat, took a couple of practice swings and stepped in. I dug a little groove with my back foot so I could push off and get some power. The first pitch was a little high, but close enough, and I swung hard and…missed. That was a surprise; I never miss a pitch in softball. The second pitch was right over the plate. Swing and…miss. I stepped out for a second and took a deep breath. And a practice swing. My heart was pounding. When the next pitch came, I ripped at it and barely touched it, sending a slow roller to the mound. I would have beaten it out, but it was an easy force play at the plate and the inning was over.

I couldn’t believe it. I went to grab my glove and Dad said, “Wow, you really hit that ball!” out of the corner of his mouth, which is how he’d spoken since the stroke. I replied, “No, that was pathetic. I hit a tiny roller to the mound. But I’ll do better.”

I would get to the plate for a chance to make it up two more times, once with the bases loaded. And each time I nearly struck out, just barely tipping the ball on my final strike. None of the balls made it past the mound. I was dumbstruck and angry with myself.

The game was called a little short because a huge storm loomed. Everyone hurried toward the barn. As I wheeled Dad over, he again commented on my prowess at the plate, and I said, “Dad, that’s never happened to me before. I almost struck out three times and each time just barely tipped it.”

Dad was pretty fearless his whole life—until the stroke which played havoc with his mind and body. If something good came from it, it was that it loosened his grip on his emotions. One of them, however, was fear. And as we neared the barn, the wind began to howl and the sky had that eerie green that precedes a tornado. Dad insisted we head home. I had just gotten his big frame into the front seat and the wheelchair in the back when a bolt of lightning struck so close that everything shook with the simultaneous boom.

We crept along the tree-lined driveway in one of the worst storms I’ve ever seen. Small branches flew through the air. Even with the wipers on fast, I could barely see. When we got onto the road, I snaked my way around fallen branches and big trees, backtracking when there was no way forward. Dad worried. I said we’d be OK. Two hours later, we made it home.

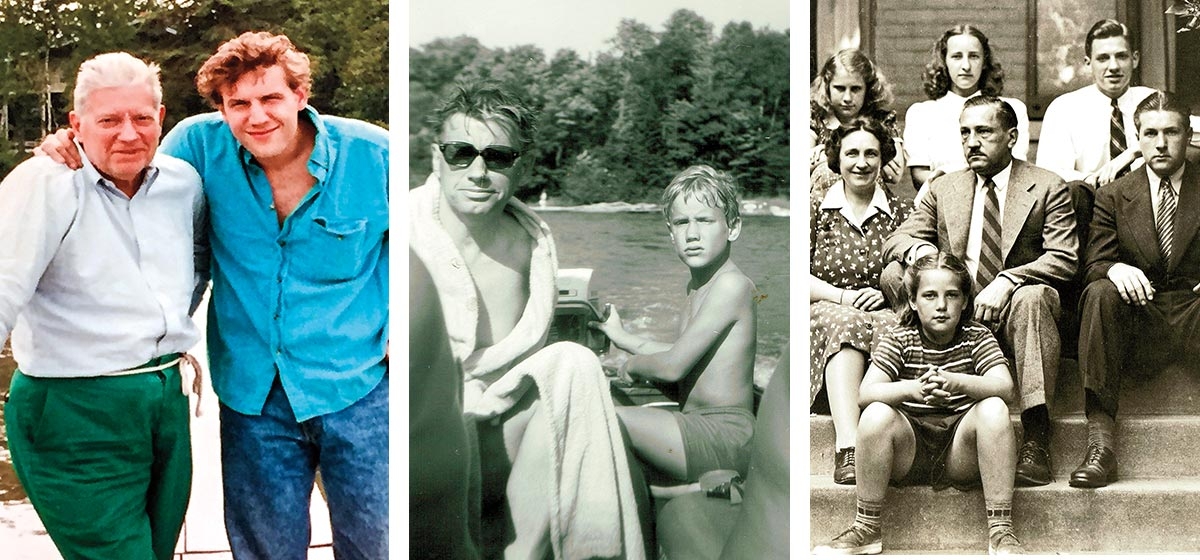

For the next week, Mom took care of the kids when they took afternoon naps, and I visited Dad in the nursing care room where he’d recently moved. For an hour and a half each day, I interviewed him about his life. I had a tape recorder and we talked about all sorts of things, including two he’d never discussed much, the accident that killed three of his four siblings and his experiences in the Pacific on a doomed World War II destroyer.

In 1940, Dad’s older brother and two of his three younger sisters were killed by a train late at night when they were returning from our place in Michigan. They were 22, 12 and 9. Dad was 20 and he and his other sister, 16, were not in the car. The “accident,” as it would forever be known to us all, dominated the front pages.

The story of his four years as an officer on a destroyer comprises all the human aspects of war: Courage and heroism, humor and ridiculousness, fear and panic, death and destruction, and survival and recovery. Luck and the fact that he’d been a college swimmer helped Dad to be among the minority who survived when his ship was hit simultaneously by two kamikazes and sunk in shark-infested waters off Okinawa.

That’s as far as we got. I figured we’d have time for the rest of his life on another visit. As robust as he’d always been, Dad was then equally weak, falling asleep in his bed sometimes as he spoke. Often he closed his eyes as he remembered people and things from long ago, sometimes a tear forming in his eye. His great heart was simply nearing its end.

The phone occasionally rang, and it was my nephew who has cerebral palsy and understood being in a wheelchair. Dad coached him on how to beat out his seventh-grade rival and win the affections of Bethany, another seventh-grader in his special needs school. Sometimes, the attendant came in to help Dad. He was a friendly black guy in his 40s and Dad had taught him about the stock market and economy in the weeks they had together.

To my dismay, the other thing that kept coming up was the softball game. “Boy, you really hit that ball,” Dad would repeat. And I, ever the young journalist, would correct him, albeit gently. “Well, actually, I don’t know what happened, but I barely avoided striking out. It was embarrassing.” Every time he brought it up, he did so with pride. Every time I corrected him, I did so with pain.

Back at home, Mom and I were sitting in the kitchen one day, looking out at the driveway. She asked if Sam and Lidey, our oldest and middle child were getting along any better. And I said, “Mom, I don’t know what you mean—they get along great. There’s no problem there.” Just on cue, little Lidey toddled into view on the driveway, and her older brother then appeared behind her wielding an oversized pink wiffle ball bat, hammering her on the head. Oh well…

On our last day, I wanted to take Dad out to his farm, which he loved. A bunch of the family came too. I said I’d drive Dad out—the kids would be in the back seat—and then we’d drive back to Pittsburgh from the farm, and my sister Nancy and her husband Ted would drive Dad home.

It was a hot, hot day in early August. As we drove through the small Ohio towns, the kids slept in the back and Dad nodded off in the front, his slouching form held by the seatbelt. The Reds game crackled on the radio, and it was just like old times, except the roles were reversed.

When we got to the farm, the others were already there. After a walk and a picnic lunch, Dad wanted to get out of the sun. The stroke had damaged his ability to cool himself, so I wheeled him over to the gnarled, old maple tree that still stands today in what had been the front of the old house before it burned down. It’s one of my favorite trees.

Dad and I sat there, he strapped in his wheelchair and I on a big root next to him. We looked down over the field to the three-acre lake he’d built in the ‘70s—I always thought because I loved fishing and he wanted me to like the farm. But I’m sure there were more practical reasons. In the shade of that maple, we appreciated the breaths of wind when they came. We spoke of many things, and at some point, my brother-in-law Ted called to say that they were ready to head back. Dad would go with them, and the kids and I would return to Pittsburgh.

“Boy, you really hit that ball the other day,” Dad said out of the corner of his mouth. I sat there, looking over the field, down to the lake. And finally, I saw the light.

I paused for a long moment, and then I said, “Yeah, you know, when we got there, I didn’t know if I’d even get a chance to hit. But one of the guys called me to grab a bat. And so I did. The bases were loaded. And I remember Grant Hesser was out in left field, and he was yelling in ‘Easy out—Easy out.’ I stepped into the batter’s box and asked for timeout, as I dug a little groove for my back foot. So I could push off and get some power.

“The first pitch came in high, and I took it. ‘Hey, what do you want?’ said Tots Hinch the pitcher, ‘I know it when I see it,’ ” I said, referring to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, a Cincinnatian they’d known, and to whom Dad had introduced me when I was a boy.

Dad appreciated that. He laughed. And listened.

“Tots said, ’Well don’t wait forever. That storm is on its way, and it looks like a bad one.’ And that was true. The wind was picking up and lightning flashed in the distance.

“The next pitch came floating in. It looked as big as a volleyball, and it was as if I could see it in slow motion. My arms coiled like a spring, and I pounced.

“There was a tremendous CRACK! Hinch flinched to cover himself, but then just looked up. So did the shortstop and the third baseman. Out in left field, Grant Hesser didn’t even move. He just looked up as the ball carried so far over his head that it might as well have been a migrating bird. And the ball just kept going and going. It went out of that field and over some trees that were a ways into the next field. Never to be found. For a moment there was silence. Then, everyone cheered.”

The look in Dad’s eyes said it all. I quickly stood up and got behind his wheelchair to hide the tears in mine. He laughed as I wheeled him back. “Hesser just looked up … Ha ha ha ha …. That’s just great.” “Yeah,” I said, “It was probably 60 feet over his head.”

“60 feet over his head,” Dad said. “That’s beautiful!”

We got to the cars, and everyone packed their stuff. I got the kids in their carseats, and then I helped Ted wheel Dad up the ramp into their gray Toyota minivan. I shook Dad’s hand and stepped back, as Ted turned the ignition.

Dad turned his neck as far as he could, which wasn’t far, so he could see me out of the corner of his eye. And as he sat there stiffly, he raised his good arm and gave me a salute. And I waved goodbye, suddenly knowing it was the last time I would ever see him.