The recent celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the University of Pittsburgh’s polio vaccine recalled one of the great moments in Pittsburgh history. Led by Dr. Jonas Salk, the scientists were armed with expertise, belief and will. I got to know Salk just 11 years ago and wrote a three-part profile about him. But I never wrote about what to me was the most interesting part.

The story came about when a friend called about her son who had died as a young man. She’d been told it might have been due to a bad batch of polio vaccine and asked me to check. I did but found nothing, save the occasion to learn about the turmoil, controversy and fear of that era when children were contracting polio and no one knew why. And I learned a little about Salk, the decisive figure in the victory.

It was 1994, and nothing had been written about him of any note in years. He granted few interviews and none that I saw of significant substance. He was about to turn 80, and I proposed doing a story on Salk at 80 that could also give us “fresh material” when the time came for an obit.

I contacted his secretary in La Jolla. An interview wasn’t likely, she said. Salk, it turned out, generally detested reporters. I kept trying, though, calling periodically and striking up a friendly phone conversation with the secretary, a friendly Pittsburgh native. I read several books to prepare so that if opportunity arose, I’d be ready. I interviewed people who knew Salk or had worked with him, and two opposing pictures developed.

One was of a great humanitarian and visionary, a man generous with his time and spirit. The other was of a cold, single-minded agent interested in his own success and fame.

“At the beginning, I saw him as a father figure,” a polio research colleague said. “And at the end, an evil father figure.” Salk was faulted for the unprecedented publicity he got and for not sharing the credit for the vaccine. His colleagues kept that grudge, never accepting Salk into the National Academy of Sciences.

I had just about given up when one day the phone rang and the voice said “Jonas Salk.” I assumed it was a colleague pulling my leg. “So, Dr. Salk, yes, uh, where are you calling from?” I asked looking around the newsroom to smoke out the ruse. “San Diego.” It was Salk, and I tried to recover and get down to business. I wanted to prove I’d done the research and merited an interview. It worked, and he agreed to see me in La Jolla.

I was full of expectation when I arrived at his house, which he shared with his wife, the artist Francoise Gilot, the former companion of Picasso.

Salk answered the door. There were a few pleasantries but not many. It was clear he wanted to get started, which we did. The tone, however, wasn’t right. No rapport. His answers were short and increasingly condescending. “What you meant to ask was…” he said a few times. So it went. About 45 minutes into it, Salk looked at his watch and asked “Are you going to wrap this up soon?” As I began to answer, he interrupted: “I mean, any time short of midnight?” It was 3 p.m. I wasn’t close to finishing, but said I had just a few more questions. I plowed through quickly, heading for the tougher ones about not sharing credit. Salk was irritated. We wrapped it up.

What a waste of time, I thought afterwards. So much research. And such arrogance. The detractors were right about Salk. His secretary called to see how it had gone. I told her not well but thanked her and said it was worth the shot. The next morning, however, the phone rang, and it was Salk. He apologized for the day before, saying he had just flown back into town, “and at my age, it gets fatiguing.” Did I want to talk further?

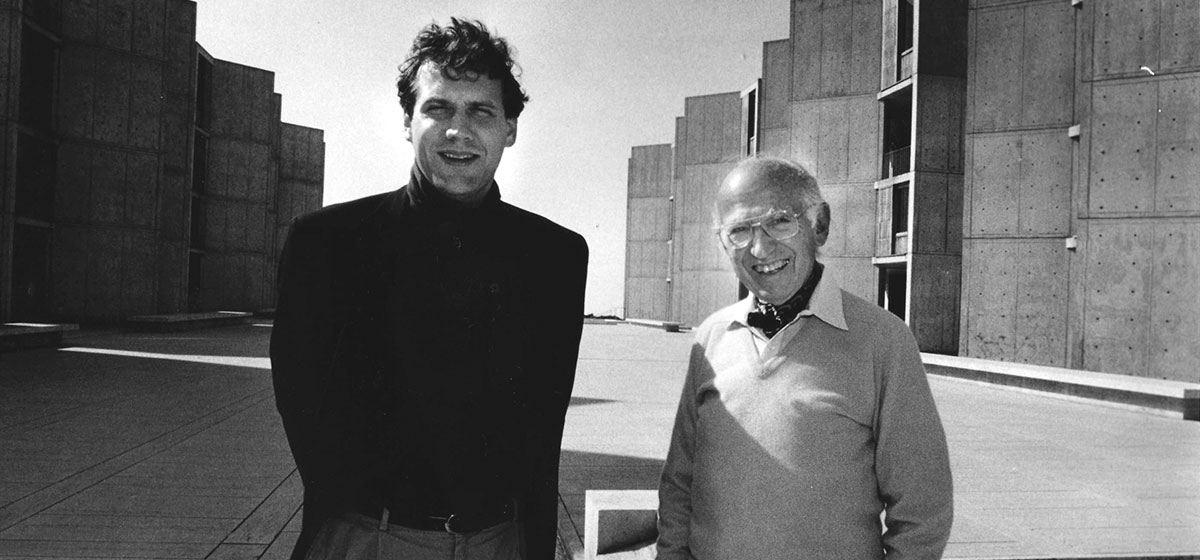

When we met that afternoon, it was a different Salk. “Perhaps I could be a guide as much as a source,” he said. We spent most of the next two days together. He showed me all around the Salk Institute, which had become a major biotech generator for San Diego. The architectural masterpiece by Louis Kahn features two stark, white concrete sides lining a courtyard. In the middle of the courtyard a canal of water leads the eye to the end of the corridor and the vast, blue Pacific.

We talked about many things. He considered newspapers to be “the daily pathology report” and suggested that I “study success” instead. What was wrong with the world was obvious. More rare were the people who could solve problems.

“Some people say where there’s a will there’s a way,” Salk said. “I turn it around. Where there’s a way, there isn’t always the will.” Since then, when things seem inscrutable or the obstacles too many, I’ve thought of that comment and its implicit reproach. The next night was his 80th birthday party, an event marked by speeches and dignitaries. Salk introduced me to many Nobel Prize winners, including James Watson and Francis Crick, the discoverers of DNA, and Renato Dulbecco, credited as spawning the Human Genome Project. It was a triumphant evening for Salk.

He died later that year. At the time, he was working on a cure for AIDS. His legacy to the world is clear, as the conquering hero of polio. His legacy to Pittsburgh is also considerable, as the most famous in what has become a long line of internationally known researchers at the University of Pittsburgh. He believed in risk and trying to improve the world.

“Risks always work out,” he said. And though we spoke for the better part of three days, the only things I remember Salk saying are the quotes in this story, including his parting comment: “Do that which makes your heart sing.”