The Hopi’s Last Hope

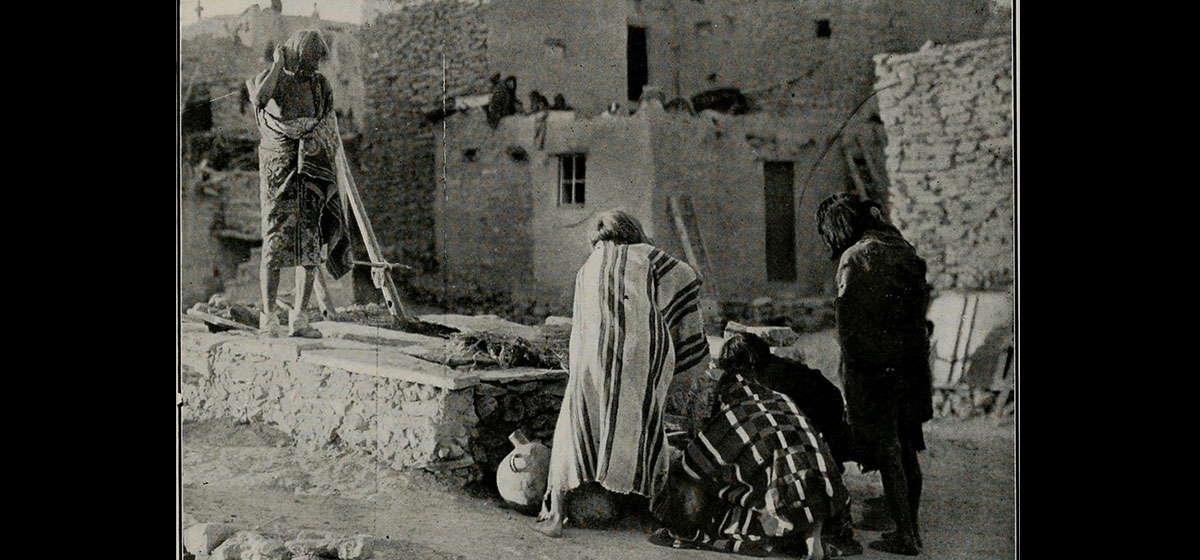

My new friend, Abbott Sekaquaptewa, had walked me through the history of the Hopi tribe, beginning with their birth as children of the Earth Mother up to about AD 500, when the Hopi had hired a fierce Apache tribe to protect them.

As I noted last week, although the Hopi owed their entire continued existence to the Apache, the Hopi nonetheless loathed their protectors. Eventually, this got old and the Apache decamped for greener pastures.

Again, it seemed as though it was lights-out for the placid Hopi, but, remarkably, they were once more saved at the last moment. Their savior this time was the Spanish conquistadors, who kept the Hopi’s enemies occupied for many decades. Of course, the Spanish also enslaved the Hopi, but at least the Hopi survived.

Eventually, the Spanish were expelled by the Americans, who were (slightly) less obnoxious than the Spanish. The Americans didn’t enslave the Hopi, but they did try to make good Christians of them and to Anglicize them. The Hopi resisted and eventually a number of Hopi parents were incarcerated at Alcatraz for refusing to send their kids to American-style schools.

For all their complaints about the Americans, though, the Hopi were at least protected by American cavalry troops and, later, by the hated Bureau of Indians Affairs (BIA).

But while the Hopi had dodged annihilation yet again, the Americans tended to look the other way as the aggressive Navajo slowly swallowed up more and more Hopi land. Following the “Long March” and the return of the Navajo to their northwestern New Mexico reservation, the Navajo quickly expanded northwest into Utah and—unfortunately for the Hopi—west into Arizona.

The Hopi “fought” the Navajo mainly by filing complaint-after-complaint with the BIA (these were mostly ignored) and then lawsuit-after-lawsuit in the American federal courts. No fewer than three of these litigations ended up at a bewildered U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court clearly felt that the Hopi were in the right, but the good Justices were also deeply frustrated by the Hopi’s inability or unwillingness to stand up for themselves, to push the Navajo back where they belonged. In effect, the Hopi wanted to replace their Apache protectors, their Spanish protectors, their U.S. Calvary protectors, and their BIA protectors, with a U.S. Supreme Court Protector.

But no matter what decisions the Supreme Court handed down, the Navajo casually ignored them and the Hopi reservation continued to evaporate. Eventually, the facts on the ground had to be acknowledged, and new Hopi and Navajo boundaries were established, resulting in a very much reduced Hopi reservation. In between these two boundaries, in a kind of sop to the Hopi, was an “Area of Joint Use” which could be used by either tribe.

Unsurprisingly, the “Area of Joint Use” quickly became the “Area of Heavy Use by Navajo and No Use by Hopi.” (Humiliatingly, the Hopi reservation is itself mainly located in Navajo County, Arizona.) And that, said Abbott Sekaquaptewa, was where matters pretty much stood.

The immediate problem the Hopi faced, and the one Abbott wanted my help with, also (surprise, surprise) had to do with the nasty Navajo. In the early 1970s the Mohave power plant had been built in Laughlin, Nevada, and in the mid-1970s the Navajo power plant had been built on Navajo land near Page, Arizona.

The energy feed for the plants came from coal mined at the Black Mesa and Kayenta mines near Kayenta, Arizona. The Black Mesa Mine supplied coal to the Mohave plant 273 miles away, via a unique coal slurry pipeline. Water for the pipeline was pumped from the Navajo Aquifer.

The Black Mesa and Kayenta mines, and the Navajo Aquifer, lay primarily on Navajo land, although they also extended into the Area of Joint Use, mentioned above.

According to Abbott, not only were the Navajo hogging all the living space in the Area of Joint Use, but they were also hogging far more than their fair share of the coal royalties. As if that weren’t bad enough, so much water was being pumped out of the Navajo Aquifer that the Hopi wells were drying up.

The Black Mesa and Kayenta mines were owned by Peabody Coal (now Peabody Energy). In the mid-1960s the Navajo and Hopi had signed royalty agreements with Peabody, the tribes having been represented in those negotiations by a lawyer who was secretly employed by Peabody. Needless to say, the royalties were extremely low.

The Navajo and Mohave power plants were owned by four very large western utility companies: Arizona Public Service, Nevada Power, Pacific Gas & Electric, and Southern California Edison (where my friend, Jack Moore, worked). The utility companies were happy with the Peabody arrangements, which assured cheap coal supply to their power plants.

The Navajo were raising holy hell with the utility companies and Peabody, using their sophisticated Tribal Chairman, Peter McDonald, to mount a powerful public relations effort. The unfortunate Hopi, however, seemed to have no idea how to assert their claims.

Back in my squandered youth I was a lawyer, and lawyers certainly know how to get justice for their clients: you sue the hell out of everybody and then negotiate a settlement. Unfortunately, the Hopi hadn’t enjoyed much success in their many lawsuits against the Navajo over the years, and Abbott had little confidence in that approach.

“No problem, Abbott,” I said. “We’ll draft a lawsuit, just to show the bastards we mean business, but then we’ll negotiate a deal in lieu of litigation.”

I plopped myself down at the small desk in Abbott’s office in the Tribal Council Headquarters and began to sketch out the outlines of the Hopi’s vast lawsuit against Peabody, the four utility companies and the Navajo Nation. They would regret, I told the Tribal Chairman, that they had ever messed with Abbott Sekaquaptua.

Eventually, I paused in my labors and looked up. “What exactly is it you want from these guys, Abbott?”

“Money,” said Abbott.

“Ah. From the Navajo or the companies?”

“Don’t know.”

“Ah. How much money do you want?”

“Don’t know.”

“Well, Abbott, not to be a nuisance, but if you don’t know what you want it’s going to be damned hard to convince these people to give it to you.”

Abbott thought about this for a long few minutes, then stood up and said, “I need to call a meeting of the Hopi Tribal Council.”

That sounded eminently sensible. But, as we’ll see next week, it wasn’t sensible at all.

Next up: Abbott Sekaquaptewa, Part III