The Heart Can’t Heal—or Can It?

Having a heart attack was like having an elephant jump on my chest and sit there for six hours, then wander off into the night as though nothing had happened. Having sextuple CABG surgery was like being in a really bad car crash.

As between the two, if you ask me, there isn’t much to choose. I mentioned this to a cardiologist friend of mine, a thoughtful and humble fellow in a profession where both qualities are hard to come by.

“If I had to choose which one to go through again,” I said to my friend, “I might choose the heart attack. Awful as it was, I survived it and maybe my heart would just get better on its own and I wouldn’t have to go through another car crash.”

But my friend shook his head. “I hear you,” he said, “but hearts don’t get better on their own. The only way to avoid another CABG-car-crash is not to survive the next heart attack.”

Well, given that choice…

I forgot about all this for a while, but one day, slogging up Negley Hill, I was certain that I was having another heart attack. The world got very dim and I couldn’t breathe. I was dizzy and was afraid I might fall sideways into oncoming traffic.

It turned out that I was just coming down with the flu, and when the flu was over I was as-bad-as-new. A few weeks later I was heading up that damn hill again, imagining my poor, scarred heart struggling to beat hard enough for me to make it to the top and wondering what its lunatic owner thought he was up to.

And that’s when it hit me. Wait a minute, I thought, hearts can get better on their own!

When people say they’ve had a heart attack, what they usually mean is that they had a cardiac artery attack. An artery closes up, the heart is denied its blood-oxygen supply, heart muscle dies, this screws up the electrical conductivity of the heart, the heart goes into fibrillation, and you die. But there was nothing originally wrong with the heart—it was the arteries that were bad.

I didn’t die during my heart attack, despite the massive damage my poor heart incurred, because of something called angiogenesis. I’ve written about that before, back in 2014, and since, like all bloggers, I’m an indolent SOB, I simply repeat it here:

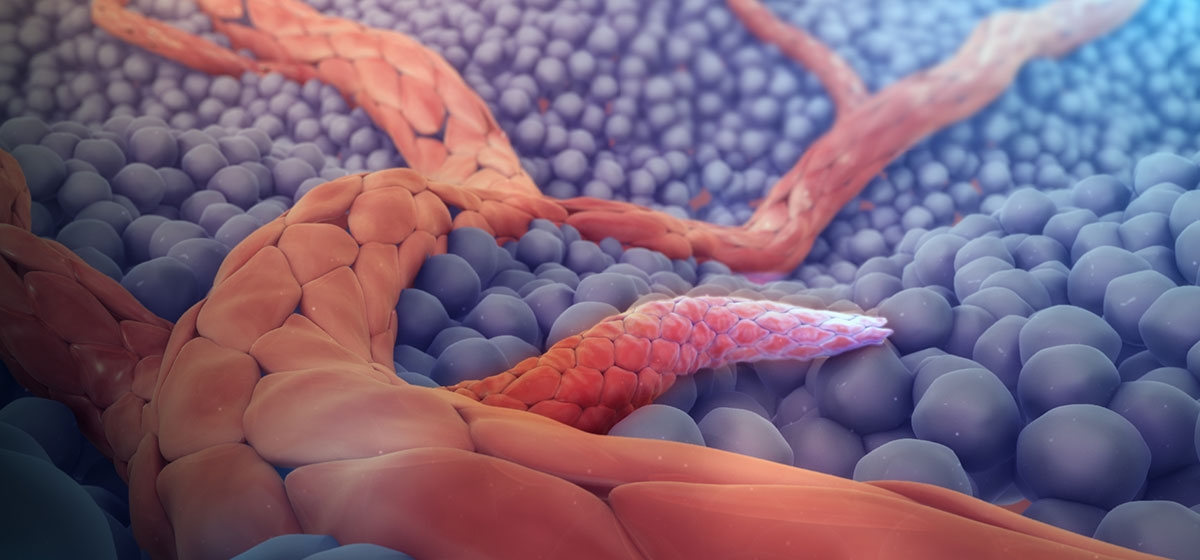

“[A] healthy human heart has an ace up its sleeve: angiogenesis, the process by which new blood vessels form. It sounds science fictionesque, but it’s a common and well-known phenomenon.

At some point in time in my life, probably in my early sixties, the deteriorating condition of my coronary arteries caused my heart to move to Plan B: launching the process of angiogenesis. Since the heart wasn’t getting enough blood from the arteries, tiny new blood vessels began to form, spreading out across my heart like it was the Mississippi Delta, showing up on an MRI scan as what scientists call “blushing.” Each of these vessels was small, capillary-like. But, in the first place, there were a great many of them, and, in the second place, capillaries are actually much more efficient at delivering oxygen to heart muscle than are larger vessels.

Which brings us to the evening of June 24, 2014. Without angiogenesis, that is, the growth of new vessels in my heart, I would have suffered the classic Type 3 myocardial infarction: sudden cardiac death. Painful, but brief and decisive. Instead, as the battle raged between a capillary-fueled heart-that-refused-to-die and closing-arteries-that-refused-to-let-it-live, I suffered what was, in effect, a six-hour heart attack.

At first, shortly after the attack started, heart muscle began to die and my lungs began to fill up with fluid. But, very gradually, the newly formed capillaries began to deliver oxygen to my heart faster than the old, clogged arteries could kill heart muscle. By six a.m. on the morning of the 25th I was able to fall asleep, mostly out of exhaustion, and when I woke up at 11, I didn’t feel that bad. In fact, we continued our tour of France for roughly another week.”

The new capillaries hadn’t formed spontaneously. What had provoked the phenomenon was the combination of reduced blood supply due to the narrowing of the arteries combined with vigorous exercise. My heart was receiving ever less oxygen from its main, narrowing arteries and yet the vigorous exercise was causing the heart to demand ever more oxygen. The solution was angiogenesis.

Little understood even in 2014, angiogenesis is now being used in a rapidly expanding group of therapies. Pro-angiogenic therapies are being used to fight heart disease (it’s about time, guys), while anti-angiogenic therapies are being used to fight cancer, which needs blood supply to thrive.

Clearly, then, medical science has been, for roughly a century, wrong about the question whether the heart can heal itself. This raises serious questions about the appropriateness of barbarous surgeries like CABG, which in my case was worse than the disease. But it isn’t just angiogenesis that puts the lie to the old unhealable-heart thesis. Next week we’ll look at two somewhat similar phenomena: arteriogenesis and collateralization.

Next up: Opening the Medical Mind, Part III