The Culture of the Scots-Irish

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” –Peter Drucker (supposedly)

Whether or not Drucker ever said that, every corporate executive knows it’s true. No matter how brilliant a strategy might be, if the corporate culture is toxic, the strategy will fall as flat as soggy Cheerios. On the other hand, if the corporate culture is healthy, a whole series of brain-dead strategies won’t matter because the firm will live to eat breakfast another day.

On the other hand, when we begin to espouse healthy or unhealthy cultures as an explanation for the poor outcomes achieved by certain groups in human societies, we need to be very careful. Yes, human cultures are very powerful, and it’s often impossible to understand why some groups succeed and others fail without understanding the cultural legacies that have influenced them. But all too often cultural explanations can slide over into—or serve as a thin disguise for—racism, xenophobia, or other forms of bigotry.

But today we’re talking about white people, so what the hell… To understand the Appalachian culture in America we could start, as J. D. Vance did, with Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling book, “Outliers.” “Outliers” contains a chapter on Harlan, a town in southeastern Kentucky that lies 30 miles east of Barbourville, where my grandparents lived, and 49 miles south of Jackson, where J. D. Vance’s grandparents lived. (Both distances are as-the-crow-flies; driving distance is much longer.)

Harlan, known as “Bloody Harlan,” is an extremely violent place. (There is, by the way, a terrific television series on the FX channel called “Justified,” based on a story by Elmore Leonard, that takes place in Harlan.) The chapter in “Outliers” tries to understand why Harlan should be such an intemperate, almost ungovernable place, and in the course of his argument Gladwell takes us back to the Scottish Lowlands, Ireland, and northern England, where the Scots-Irish immigrants originated.

In those places the Scots-Irish were cattlemen and sheepherders, not farmers. A farmer, Gladwell notes, can go to sleep at night feeling reasonably certain that when he wakes up in the morning his carrots will still be there waiting for him. But a herder has no such confidence; when he wakes up in the morning some miscreant can easily have made off with his livelihood.

This led the Scots-Irish to become intensely distrustful of anyone outside their families, and also to react with violence to any attack on their family—including, of course, stealing their animals. This “culture of honor” (to use the sociological term for it) was carried with the immigrants when they came to America just before the Industrial Revolution. (We might note how similar this phenomenon is to the gang culture in inner city African-American neighborhoods.)

The Lowlands Scots and northern English became, under the influence of John Knox, Calvinists and Presbyterians. In the seventeenth century, many of these people migrated to Ireland, seeking to avoid persecution by the Church of England and also seeking better economic opportunity. But faced with continued persecution, these people, now known as the “Scots-Irish,” migrated again, this time to America.

The Scots-Irish were certainly characterized by an intense loyalty to family and a concomitant distrust of anyone who wasn’t family. This characteristic no doubt arose, as Gladwell supposes, from the insecurity of their lives as herders.

But they also evidenced other distinct characteristics. For example, a dislike of government (or, for that matter, anyone who wanted to tell them what to do), resulting from their conflict with the English crown and the Scottish and Irish Catholics over religion. In addition, they developed a stern independence of spirit and a stubborn pride in their religion and their manner of life. This inward turn might well have been precipitated by the constant turmoil that afflicted the borderlands between England and Scotland for many years.

Finally, the Scots-Irish had hair-triggers in the face of provocation, arising out of the need to react promptly and forcefully to attacks on their livestock. Interestingly, that made them useful soldiers when the American colonies revolted against England. In 1780 a Scots-Irish militia, the Overmountain Men, defeated the British at the Battle of King’s Mountain, an unexpected setback that forced the British army to abandon its southern campaign. This event might well have marked the turning point in the American revolution.

When the early Scots-Irish migrated to America they landed overwhelmingly in Pennsylvania, where they could practice their Presbyterianism unimpeded. Since all the good land near the coast had been spoken for, this early group moved west, settling in Chester, Dauphin, and Lancaster Counties in east-central Pennsylvania.

But as more and more Scots-Irish families arrived, they found that the entire coastal lowlands was full-up. These later arrivals (in the early-to-mid 1800s) split into three streams. One stream headed south, through the Shenandoah Valley into Virginia and on south to the Carolinas. (To this day, North Carolina boasts a larger percentage of Scots-Irish than any other state.)

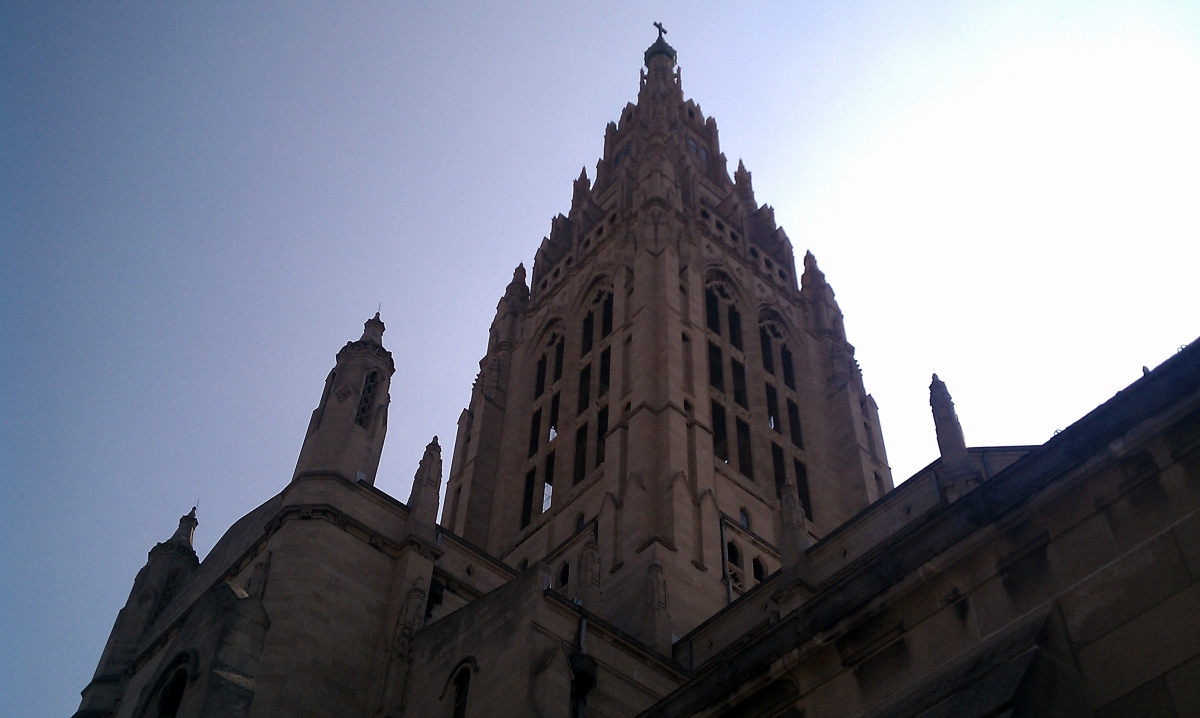

A second group, by far the most successful, moved due west across the Allegheny Mountains to Pittsburgh. This group maintained their Presbyterian faith and many became wealthy and prominent. They built monuments to their Presbyterianism, including the remarkable East Liberty Presbyterian Church (the “Mellon church”), a massive Gothic edifice that, if it stood in Europe, would be a major tourist attraction. (Pittsburghers pay it little heed, however.) This striking monument stands 300 feet high and includes, in addition to the main sanctuary, a chapel, a garth for smaller services, a music hall, a basketball court and bowling alley (!), and hall after hall of administrative offices.

These Scots-Irish families ended up dominating both the Pittsburgh social register (to this very day), and spearheading the Industrial Revolution. Men like Carnegie (Carnegie Steel), Laughlin (Jones & Laughlin Steel), and Mellon (banking, oil and gas, aluminum, coal, glass, industrial equipment, etc.) became enormously wealthy and exercised power far beyond the modest confines of Pittsburgh. Though the Scots-Irish never represented more than 3% of the American population, fully one-third of American presidents claim Scots-Irish blood, most recently Bill Clinton.

The third branch of the Scots-Irish, and the one we are concerned with in these posts, headed southwest into the almost impenetrable mountains of southwestern West Virginia, northeastern Tennessee, and southeastern Kentucky. There they would find much less success, as we’ll see next Friday.

Next up: On Hillbilly Elegy, Part IV