The Coming Missteps on Big Tech

If we thought that too many antitrust laws and enforcements were ineffectual at best and counterproductive at worst, matters are about to become even more dreadful: Most of the proposed enforcements will harm consumers without much denting the power of Big Tech.

Previously in this series: “How to Handle the FAANGs: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part X”

I want to emphasize that, in pointing out the inadequacy of our century-old laws as applied to today’s huge platform companies, I’m not trying to be an apologist for Big Tech. I’m merely arguing that we either need to come up with different ideas about antitrust law or we need to deal with modern anticompetitive practices in other ways.

Let’s take a look at the more serious concerns about Big Tech.

The fundamental contradiction

But first, let’s examine the fundamental contradiction behind almost every attempt to attack Big Tech with antitrust laws. It goes like this:

Virtually all the consumer benefits we get from Big Tech have to do with the extraordinary power of Big Data and network effects. Lower prices, increased product choice, and exceptional convenience depend on platform companies’ ability to assemble massive amounts of data and use it to create the benefits just enumerated.

Meanwhile, almost every proposed antitrust attack on Big Tech — breaking them up into smaller companies, prohibiting them from using their data to enter other businesses, making it easy for consumers to opt out of sharing their data — compromises the ability of the platform companies to offer the consumer benefits described above, thereby harming consumers by raising prices, eliminating choice and causing inconvenience.

Keeping that contradiction in mind, let’s look at some of the key issues. In the sections that follow, I’m being intentionally provocative in order to highlight the problems associated with most of the antitrust approaches to Big Tech.

Does size matter?

As noted in earlier posts, the Brandeisians and neo-Brandeisians both oppose bigness per se, an ultimately untenable position in a global economy that is growing ever larger (and thank goodness for that).

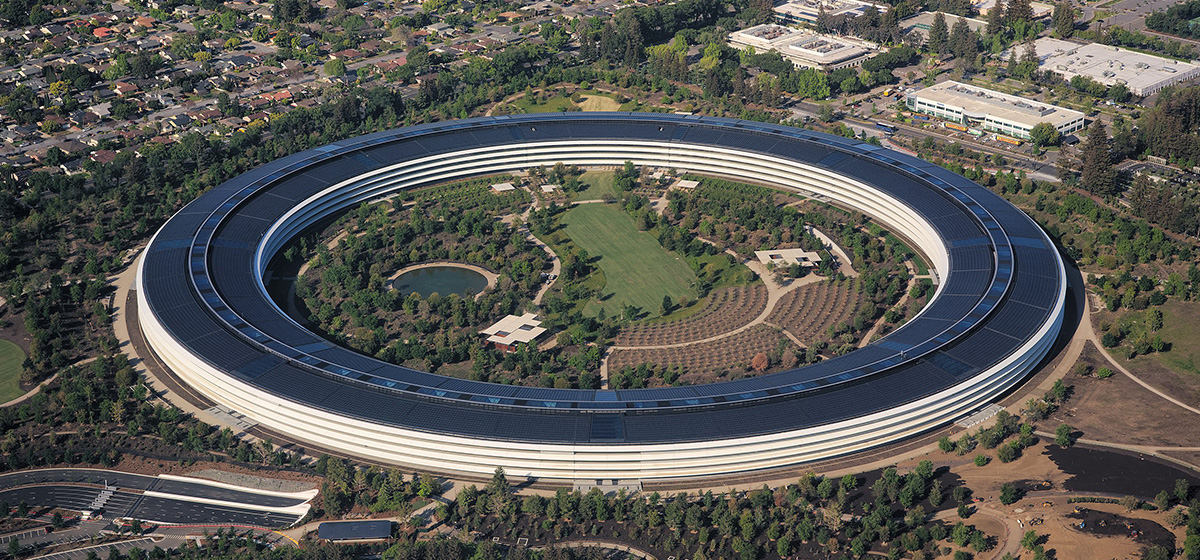

Still, there is no doubt that Big Tech is big. If the largest of them (Apple) were a country, would be the eighth largest in the world, ahead of Italy, Russia and Brazil. Amazon employs 1.3 million people. The five FAANGs make up 25 percent of the market value of the entire S&P 500.

I’m not suggesting that we couldn’t imagine a company so big, so dominant, that its scale alone would justify antitrust action to cut it down to size. But we are a long, long way from that situation now.

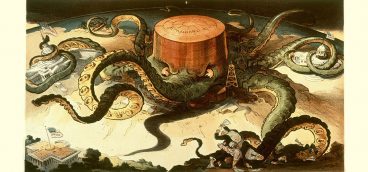

Consider the United States Steel Corporation, which, when it was organized in 1901, was capitalized at $1.4 billion. It was the first billion dollar company to exist in human history and was far larger than any other company in the world. From its headquarters in Pittsburgh, US Steel’s tentacles reached all over the globe. People were astonished and terrified by the size and power of this colossus.

But today, even inflating that $1.4 billion for the declining value of the dollar, US Steel would be worth barely more than $40 billion, not big enough to make the Fortune 500 list and a barely-visible pygmy compared to Apple’s market value of more than $2 trillion.

Yet US Steel frightened people because it was so huge! In other words, size is a relative phenomenon. US Steel seemed frightening in its day, and the FAANGs seem frightening today, but it’s only because we’re not used to seeing such behemoths. Our grandchildren will sneer at the diminutive scale of Apple.

Also, while US Steel stood alone in its immensity, dominating not just the global steel industry but every other corporation in any industry, mighty Apple is barely bigger than Microsoft, Google, or Amazon. And the FAANGs compete vigorously with each other — in social networks, app marketplaces, enterprise software, video games, news aggregation, messaging and so on.

Finally, just being big — even as big as Apple — doesn’t mean you dominate your industry. Apple controls less than 15 percent of the global smartphone market, which is dominated by Huawei and Samsung. Apple’s computers control about 9 percent of the market, which is dominated by Lenovo, HP and Dell.

At the end of the day, breaking up successful firms just because they’ve become big is little more than a decision to cede tech dominance to China.

Privacy

Internet privacy, as opposed to Internet security, is a vastly complex subject. And yet, it is one of those issues that galvanizes activists but which most consumers find to be yawn-inducing. The reason for the relative lack of interest on the part of the public likely arises because of the world we live in.

I don’t know about you, but from the time I back out of my driveway in the morning until the time I park at my office, I am followed inch-by-inch by municipal security cameras, state security cameras, federal security cameras, and, of course, the ubiquitous residential security cameras.

And that’s to say nothing of the license plate cameras that follow all of us everywhere we go. Vigilant Solutions, which is only one of several vendors of scanners and data, has a database of license plates that now holds more than nine billion scans in the United States alone, and there’s nothing any of us can do about it. The police don’t even need a court order to access the database; they just do it.

When we shop at Home Depot, security cameras follow us around everywhere we go. Most people would consider this far more “intrusive” than a cookie following us around on the Home Depot website. After all, that’s actually us on the security camera. Home Depot knows where we go, what we buy, who we’re with.

In other words, the days when we could go blithely about our business secure in the knowledge that our privacy is intact are long, long gone. And in the case of security cameras and license plate readers, as in the case of the big box Home Depot, it’s us they are following around.

By contrast, when we surf the web, what Big Tech is following is something called “HTTP cookies.” We’ll take a closer look at cookies, and at how concerns about privacy can go badly wrong, next week.

Next in this series: “The Ridiculous Instagram Case: Antitrust Is More Interesting Than You Think, Part XII”