Before the civil war, what black community existed in Pittsburgh largely included Northern-born free blacks and runaway slaves, many of whom had traveled the Underground Railroad.

This small black population would preside over a new generation of African-Americans arriving from the South. In that first Southern, black migration, the city’s African American population grew from about 2,000 in 1870 to more than 20,000 in 1900. These Old Pittsburghers formed an elite who embraced the values of hard work, responsibility, self-help, and racial improvement—values that they would inculcate into the thousands of black migrants who continued after the turn of the 20th century.

These early Southern migrants endured the humiliations of white Pittsburgh when waiters salted their coffee in downtown restaurants, nickelodeon parlors charged them double the price they charged whites, hotels insisted that they use the freight elevator, and white-dominated unions refused them membership. Undaunted, Southern migrants followed the advice of the “Old Pittsburgh” black elite. They worked hard and minded their manners. They sought to improve “the race” in the places allotted to them. And on the eve of World War I, black Pittsburgh was considered a precocious and exemplary New Negro community.

The Southern migration continued and even accelerated, with more newcomers coming from the deep South. While the population of white Pittsburgh remained virtually flat, Pittsburgh’s black population rose from 37,500 in 1920 to 62,200 in 1940. And the social gaps in the black community grew. “Things became awful,” recalled one of the Old Pittsburghers, “Big Jim” Dorsey in 1920. “Loud and wrong Negroes came bounding into Pittsburgh. They had switchblades, loud tempers, and very quickly the white population began restricting Negro privileges in the city by closing doors that had always been open to us.”

The Hill District emerged as the cultural and commercial center of black Pittsburgh. Its shops and clubs, meeting halls and taverns, pool halls and groceries, churches and parks attracted African-Americans from across Pittsburgh. On the eve of the Great Depression, the Hill was a poor, black, urban neighborhood. Social workers labeled its housing as “slums” and described it as “over-crowded” and “unfit.” To others, though, the Hill had become Pittsburgh’s Harlem, a neighborhood that “spoke the language of jazz.” It catered to Southern immigrants with dream books, folk remedies, policy rackets, and voodoo fixes that existed side by side with the Old Pittsburghers’ Loendi Club and Wylie Avenue Literary Society. Rent parties and wine rooms flourished upstairs, a dozen bars jumped all Saturday night downstairs, and vendors strolled the streets each evening selling their wares.

By 1930, Pittsburgh’s black population was 55,000—sixth highest in the nation—and the Hill District was home to 25,000 of that number. They toiled by day, prayed on Sundays, and played ball and jazz whenever they could. Due to the Depression, most of the thousands of men and women who left the South looking for better wages, better schools, and better living conditions, found themselves trapped in poverty. The jobs promised by the steel and coal industries had disappeared. Unemployment reduced many to subsistence and made return impossible. The hostility that migrants faced spoke with two distinct voices—white racism and black classism. White racism kept Southern African Americans out of unions, neighborhoods, hospitals, swimming pools, hotels, and restaurants, and restricted them in movie theaters, ball parks, playgrounds and music halls. Old Pittsburghers’ class prejudice, at once benign and patronizing, looked down at them as “boll weevil” Negroes, with “cotton in their hair.” Old Pittsburghers wanted the migrants to lower their voices, work hard, and improve the race.

Among the most prominent of the Old Pittsburgh elite was the family of “Captain” Cumberland Willis Posey. One of the most prosperous and powerful African Americans in the area, the former riverboat pilot moved to Homestead in 1892. The Poseys lived in a gracious, wood-frame house on 13th Street, looking down on the library Andrew Carnegie had built for the community. Posey participated in Homestead’s African American upper class cultural activities and owned the largest black business in the Pittsburgh district, the Diamond Coke and Coal Company.

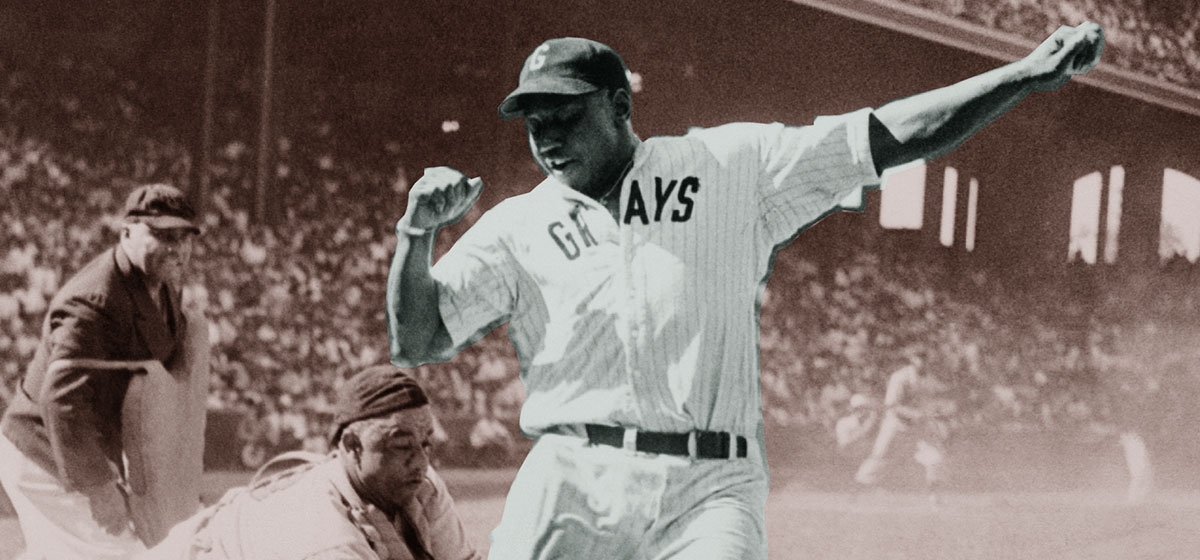

His son, Cumberland Willis Posey Jr., “Cum Posey,” was born in 1891, and in 1911 joined a local baseball team called the Murdock Grays. The Grays came into being at the turn of the 20th century as a team comprising black and a few white mill workers. It became all-black by 1910, and six years later, 25-year-old Cum Posey took over as the Grays’ booking agent and soon became team manager of the renamed Homestead Grays. He didn’t pay his players salaries until the early 1920s, when the Grays earned the reputation as one of the best black semi-professional teams in the country.

Homestead was a microcosm of Pittsburgh’s African American community. An extension of Carnegie’s Homestead Works at the Monongahela River’s edge, the steel town reached up the steep hillside that overlooked the mill. In 1879, the village of Homestead boasted a population of 302. By 1900, the Homestead Works employed over 12,000 workers and The Pittsburgh Survey labeled Homestead a “town of saloons.” Divided by class and race, Homestead had two main streets, Eighth, where European-born workers could drink at 50 taverns within walking distance of the Homestead Works, and Sixth, home to the town’s black residents. Along Sixth, black workers availed themselves of a string of saloons and brothels, pawnshops and pool halls. Black workers had arrived in Homestead in the 1890s as strike-breakers. Afterwards, they accepted jobs as non-union workers in skilled positions at the works. These relatively few skilled workers lived up along the wooded hillside, at “Hilltop.” Their lofty perch distinguished them from the majority of Homestead’s African-Americans, who worked as domestics and manual laborers and lived down in “the ward.”

At that time, Pittsburgh’s black industrial baseball league comprised only a small part of organized baseball in Pittsburgh, but Cumberland Posey’s Homestead Grays dominated black baseball in Pittsburgh.

Posey booked games against white industrial teams in the early years of the decade. For a time, he also played left field and batted lead-off for the Grays. In the 1920s, Posey converted the Grays from a local semi-pro team into a national power. There was money to be made and the best of the national black industrial teams no longer relied on local talent to fill their rosters. At a time when African American employment in the steel mills and other heavy industry plummeted, black ball players found themselves in demand. Some, like Frank Moody, who played for the Carnegie-Illinois Steel team in the U.S. Steel League, were hired just to play ball. “They didn’t like to do it openly,” he recalled. The industrial teams recruited others for the summer months only and assigned them easy jobs so they could play ball games in the late afternoon.

Between 1925 and 1930, Posey built the Grays into the best Negro team in the country. He announced his intention in the middle of the 1925 season when he signed the legendary pitcher “Smokey Joe” Williams. Between 43 and 50 years old, the Louisiana-born Williams had pitched Negro baseball for a quarter-century. Tall, part American Indian, and canny, Williams threw a fastball that “seemed to be coming off a mountain top.” Williams joined a Gray’s pitching staff that included two Negro League players already on salary, one from the New York Lincoln Giants, the other, spitball specialist Sam “Lefty” Streeter from the Birmingham Black Barons.

In 1926, the Grays won more than 100 games. This spurred Posey to add a group of Negro League all-star players. He signed future Hall of Famers “Cool Papa” Bell, “Judy” Johnson, Willie Foster, and Martin Dihigo. When the Grays signed Oscar Charleston they became one of the best teams of their era, black or white. Charleston, a tough, no-nonsense man, had played ball with Buffalo Soldiers of the 24th Infantry in Manila. His teammates said he was so strong he could open the seams of a baseball with his bare hands. He sometimes played all nine positions in a single game and was so athletic that he could charge a ball hit to center field, complete a flip, and still catch the ball.

With his array of stars, Posey scheduled more and more games against teams in the established Negro Leagues. The Grays joined the Negro American League in 1928, but when the Great Depression killed off organized black baseball, Posey returned the Grays to independent status. He saved the team by restoring a policy of playing all challengers. He could not accomplish this without an infusion of cash, and like so many Negro League owners, Posey turned to a local gambler for support. Rufus “Sonnyman” Johnson was the numbers “banker” in Homestead. Johnson owned the Sky Rocket nightclub and operated the juke box rental business for the entire Pittsburgh area. Johnson’s silent partnership saved the Grays and allowed Posey to recruit the best players available. Thanks to Johnson, in 1930 the Grays owned two spanking new Buicks and drove to their games in style.

Johnson’s presence coincided with the rise of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team that challenged the Grays for dominance in the Negro League. Like the Grays, the upstart Crawfords traced their origins to a time when Pittsburgh’s racial boundaries were vague. In the early 1920s, Washington Park served the Lower Hill’s workingclass blacks, Italians, Jews, and Poles. The park maintained a recreation center, a ball field, bleachers and facilities for basketball and boxing. The Hill’s expanding black population, however, needed a larger center and the Crawford Bath House, at the intersection of Crawford and Wylie avenues, came into being.

The Crawford Bath House functioned as both a recreational facility and a settlement house. It offered adult classes and a kindergarten in addition to a swimming pool. City park supervisors asked Jim Dorsey to take charge of the new facility. The Pittsburgh Courier reported that Dorsey was also instructed to “hire a Third Ward black politician as janitor.” The following summer, Pittsburgh’s other African American paper, The American, reported a new sign posted on the Crawford Bathhouse wall: “This House is open for bathing purposes to the Negro citizens of Pittsburgh.”

In 1926, the Crawford Bathhouse organized a rag-tag neighborhood sandlot baseball team called the Crawford Recreation Team, or the Crawford Bathhouse Team, or the Crawford Colored Giants. Most often they were simply called the Crawfords. In five years, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team of black, migrant, and working-class Pittsburghers, grew to challenge the powerful Homestead Grays—first for local and then national dominance.

Crawford games at Ammon Field, on Bedford Avenue at the top of the Hill, began at 3 p.m. or 6 p.m. When a crowd gathered—sometimes as many as 3,000 people—the bleachers overflowed. On a June day in 1930, in front of a crowd estimated at over 5,000, a young Crawfords catcher named Josh Gibson smacked four hits. Gibson worked at a Westinghouse air-brake factory, and his father labored at the Homestead mill. From the start, Gibson exuded greatness. On his first at bat for the Crawfords, Gibson hit a ball over the Ammon Field hill, over the nearby tennis courts, and into the houses across the street.

The Crawfords remained a local semi-pro team, surviving week to week by passing the hat among their fans. As the darlings of the Hill, the Crawfords clamored for a confrontation with the Grays. “Hell, you had more games played on the corner,” recalled local resident Clarence Clark. “You had your Grays rooters and, in the joints, Crawford rooters.” Posey delayed the contest, content to let interest build. Ever on the lookout for fresh talent, Posey spotted Gibson and inserted him into the Grays’ lineup in mid-summer 1930.

During the off-season, The Crawfords changed hands. Bar owner, politico and boxing aficionado Gus “Big Red” Greenlee said, “I’ll write a check.” He became the owner, and within two years built the Crawfords into the best team in Negro League baseball. Greenlee, a college graduate and veteran of World War I, possessed the credentials necessary for membership in the Old Pittsburgh black elite, except that he was a Southern migrant. He came to the city by hopping a freight train in 1916, working in the mills and then fighting in France before returning to Pittsburgh in 1920. During the 1920s, Greenlee bought several restaurants and clubs, moved his residence to the affluent Homewood neighborhood, and assumed control of the numbers racket on the North Side. A cigar in his jaws, the 6’3” Greenlee made the Crawford Grill at Wylie Avenue and Townsend into his headquarters.

Directly across Wylie Avenue from the Crawford Grill stood Woogie Harris’s barbershop. Next to Woogie’s was Goode’s drugstore. Down the street was the local musicians’ union that hosted jazz players after hours. Woogie Harris, brother of photographer Teenie Harris, collaborated with Greenlee in the numbers game. By reportedly covering an oversubscribed bet, they became the top two numbers men on the Hill. That prominence allowed Greenlee to buy the Crawfords and he set his sights on beating the Grays.

Greenlee’s Crawford Grill was the fashionable gathering place for Pittsburgh’s black elite. When the Grill featured a known jazz band, they dressed to the nines, dining in front of murals of the Caribbean. Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Joe Louis all, played at or attended the Crawford Grill. During game day, downstairs, the Crawford ballplayers dressed for their Ammon field home games. They stashed their street clothes near the cash registers and counting tables. Occasionally, Greenlee hired his players to stand outside the club as lookouts, affecting non chalance.

Within two years, Greenlee moved the Crawfords into the first rank of black baseball teams. Wealthy during the Depression, Greenlee spent his money without apparent regard to outcome. By 1932, he had added Oscar Charleston, “Judy” Johnson, “Cool Papa” Bell, Jimmy Crutchfield, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliff, and Josh Gibson to the Crawford roster. Most came from the Grays, including Gibson, who played for the Crawfords in 1930. Greenlee’s crowning achievement came with the acquisition of future Hall of Fame pitcher and showman Satchel Paige, whom he acquired from the Birmingham Black Barons in 1931. All told, the Crawfords signed three other Black Barons to the team, giving them a distinctly Southern, Birmingham flavor.

In 1932, Greenlee shelled out an estimated $100,000 to build his own ball park, Greenlee Field, a few blocks up Bedford Avenue from Ammon Field. He added lights the next year and also organized the Negro League’s annual East-West all-star game in Chicago. One observer remarked that Greenlee built his own field because “He wouldn’t use a white man’s field if he didn’t have to.” At the segregated Forbes Field, the National League Pirates did not allow the Grays to change in the club house. Instead, they dressed at the nearby Center Avenue YMCA.

Over the next five years, the Crawfords dominated black baseball. Then, as suddenly as they had risen, the Crawfords collapsed. Greenlee’s fortune, dependent on police protection, vanished in the wake of city-wide political reform. Without the numbers, Greenlee could not support his team. In 1938, Greenlee demolished his ball park. Most of the Crawford star players, including Gibson and Paige, signed with the Grays. In 1939, Greenlee gave up his position as president of the Negro National League that he had helped form in 1933. The Grays returned to their previous glory, winning pennants regularly until the integration of baseball in 1947.

Shades of black

The development of black baseball in Pittsburgh, for a short time, barely disguised the inherent class tension between the city’s black elite and its migrant working class. By playing at Oakland’s Forbes Field, the Grays accepted the limitations of segregated seating and exclusion from the club house; the Grays and Posey gratefully accepted what white elites granted them. Black Pittsburghers who attended Gray’s games in Oakland often found as many whites in the stands as blacks. The game felt more like a major-league contest, as if the Pirates were playing. The fans dressed and behaved with appropriate New Negro decorum. They took picnic baskets, and the men wore ties. “We dressed for games at Forbes like we were going to church.”

By contrast, playing on the Hill, the Crawfords played in the down-home atmosphere of a Southern barbecue, announcing their games with handbills posted on telephone polls, filling Greenlee Field’s 7,200 seats to overflowing, and encouraging local fans to sip beer. Fans heckled opposing teams and umpires from their seats and engaged in conversation players who lived down the street from them. “Players and the crowd were always mingling, even during the game,” recalled Robert Lavelle, the long-time owner of the Hill’s Dwelling House Savings and Loan. With an opposing runner on second, a fan rose in the stands and with a megaphone commanded, “You take one step off the base and I blow your head off.” He had a shotgun in his other hand. Greenlee cupped his hands and called out from behind the Crawford’s dugout to his player, “Just stay on the bag.”

At Greenlee Field, fans bet on the games openly. Unlike white baseball, traumatized by the Black Sox scandal of 1919, Negro baseball had “nothing to fix.” When the Crawfords played at home, fans bet a quarter on almost anything—the next pitch or where the ball might be hit. And they did it loudly. “Like if I got 50 cents on the Monarchs, the guy in the next seat or the row behind says he wants a piece of that,” recalled Hill resident Parker Ware. When the Crawfords played the Birmingham Black Barons, where many Pittsburgh migrants had come from, the stakes rose. And against the Grays, “These games were big betting,” Ware said. When the Grays came to Greenlee Field, “the place be ramblin’ packed,” said the Crawfords’ batboy Elijah Miller in 2004.

Greenlee Park was, in the words of one Hill resident, a “Negro” ball park. If the Grays were the establishment team, the Crawfords belonged to the migrants. The ball park echoed to jive and banter. As Harold Tinker remembered, “When we walked out on that field, it was like going to another world. I looked up at those stands in center field—what a thrill.” During the two teams’ four-way double-headers, Crawfords against the Kansas City Monarchs and the Grays against the Baltimore Elite Giants, the stands shook and the Hill pulsed with excitement.

Tricky baseball

The great black stars of the Crawfords, “Cool Papa” Bell, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Oscar Charleston lived double lives. As black men who lived in the Hill, they mingled, shopped, shot pool and leaned their elbows against the bar along-side anyone else. On and off the field, they lived lives that seemed larger than life, and that magnified and reflected the Hill during the Depression—a neighborhood of ordinary people, of shared distress and poverty and yet a place of extraordinary energy and excitement. Few moments in American life equaled the excitement at the Crawford Grill when Greenlee threw a party for Satchel Paige in 1934. The revelers, who included Broadway dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, dined like royalty.

Spectators at Crawford games remembered “Cool Papa” Bell as a man who appeared so fast “it looked like his feet weren’t even touching the ground,” or who “could steal second base standing up,” or “outrun a rabbit.” In the neighborhood, Bell dressed like a businessman, exhibited impeccable manners, and treated everyone with polite respect. Paige perfected his baseball and showman skills in Pittsburgh, first with the Crawfords and, after 1937, with the Grays. Paige’s grin and bravado catapulted him into the hearts and wallets of fans across black America. He became wealthy and beloved in an era of wide-spread poverty and misery. Possessed of unbounded confidence, Paige named his pitches “bee ball,” “long Tom,” “trouble,” and “the barber.” Paige worked to create his legend. On the road, however, he lived a quiet and solitary life, disappearing for an afternoon and returning to his hotel room with a hamper filled with fish he had caught. Then, to the dismay of his roommates, he fried them up in his room over a hot plate.

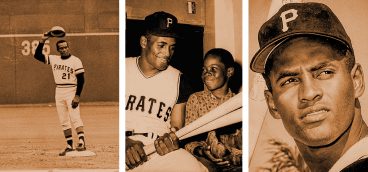

Gibson, whom major-league owner Bill Veeck called the “best hitter I ever saw,” hit home runs so hard “they went off like nickel rockets.” Lavelle, who lived on the Hill most of his life, as an old man remembered Gibson as the most phenomenal hitter of his time. Like Jackie Robinson a decade later, Gibson became The Hero to local blacks on the Hill. But, he also lived among them, on Bedford Street, not far from Greenlee field. Gibson once reputedly hit a ball so high that the umpire called him out when the ball came down the next day in Washington, D.C. Yet Gibson never made it to the major leagues. John Watkins remembered walking up Bedford in 1946, where he saw his friend Levi Williams carrying a wreath to put on the porch of Gibson’s house. Having heard that Jackie Robinson had just signed with the Major League Brooklyn Dodgers, the greatest catcher ever to play baseball died “of a broken heart.”

Gibson, Paige, Charleston and Bell left mythic legacies and lived public lives as black folk heroes. For African Americans, prowess and guile often saved the day, manipulated “The Man,” pleased the crowd, or tickled the funny bone. Bell explained, “We put emphasis on what I call tricky baseball. We tried to play with our heads more than our muscles.”

Negro League life on the road, barnstorming from town to town, speeding away from danger, “had a Southern feeling,” wrote Negro Leagues historian Saul Rogovin. Players amused themselves during all-night rides by singing gospel songs or telling tall tales. They spoke the language of the South and loved Southern food. As Paige said, “You take all those… Southern boys… first thing you know they all go haywire, living on top of the world, walking… with their jackets that say Pittsburgh Crawfords. The older fellows, we had neckties on when we went to dinner.”

The Crawfords and Grays played what Bell called “tricky baseball,” a Southern style of black baseball codified by Negro League player, manager and pioneering executive Rube Foster. Black baseball players relied on innate talent, discipline, and improvisation. The Aug. 7, 1930, game between the Grays and the Kansas City Monarchs epitomized that Southern style. A classic pitchers’ duel between the Grays’ Smokey Joe Williams and the Monarchs’ Chet Brewer, the game showcased tricky baseball at its best. Known as the “Battle of the Butchered Balls,” it lasted 12 innings.

At age 50, Williams confronted the young Brewer. A night game, the teams played under the portable lights that the Monarchs carried with them on barnstorming tours. The dim lighting enhanced the mythical quality of the game and diminished the hitters’ vision. Brewer surrendered four hits and struck out 19, including 10 in a row between the seventh and 10th innings. Still, he lost 1–0. Williams allowed only a single hit over 12 innings and struck out 25. Brewer “twirled” a masterful emery ball. Williams dropped to sidearm in the shadowy evening. Williams also covered the ball with dark tobacco juice, which made it almost impossible to see. The pitchers’ stamina, the number of strikeouts, and the length of the game made it one of the Negro League’s greatest games.

Tricky baseball, however, happened every game. Sam Streeter, who played for the Birmingham Black Barons, the Grays and the Crawfords, was known as the “Spitter King.” Pitchers worked with catchers and infielders to apply Vaseline, hair tonic, or saliva, or they “cut” the ball, scuffing the leather with sharpened fingernails, emery boards and bottle caps. They varied their deliveries—sidearm, submarine, and hesitation—as part of a repertoire to trick the batter. Tricky baseball—in truth, Southern baseball—combined Rube Foster’s practice of unorthodox strategy—bunt and run, double steal, using the centerfielder as the pickoff man at second, the hidden ball trick—with a time-honored version of “getting over.”

A term borrowed from sharecroppers’ efforts to undermine the authority of The Man, “getting over,” meant getting away with something by pulling the wool over The Man’s eyes. The Negro Leagues adopted centuries-old traditions of black rebellion and resistance and carried them north. Since there were no reserve clauses in Negro League baseball, players were not legally bound to an owner. Whenever they wished, like a Southern sharecropper, they could “skip off” to play for another team. Players came and went with the money.

Tricky baseball sought the edge wherever a player could find one. The single umpire, an amateur with authority, stood behind the mound in the Negro Leagues and often had his back turned away from a base-runner speeding around second. The speedy Bell frequently reached third on a hit by cutting across the infield in front of second base. Black baseball players cut and doctored pitches, caught fly balls with basket catches, performed flips, and generally showed off even as they played hard-nosed ball. They brought these attitudes into baseball, drawn from Southern blacks’ efforts to “beat the system” of Jim Crow segregation that rewarded individuals for their toughness, resilience, and carefully masked contempt for authority.

In 1947, Brewer, pitching in the Negro Leagues, faced the Birmingham Black Barons at Rickwood Field. Brewer hit a young Willie Mays with a pitch. The Birmingham manager, Piper Davis, walked slowly out to Mays and asked, “Can you stand up? Can you see first base? Then get over there.” In 1948, while still pitching in the Negro Leagues, Paige received a late-season call up to the Cleveland Indians in their drive for the pennant. In his late 40s, Paige displayed all the guile he had mastered in the Negro Leagues. His “Long Tom” fastball was long, but not his trickiness. Paige threw overhand, sidearm, and underhand, wiggled his glove at the top of his delivery to distract the batter, and unleashed his famed “hesitation pitch,” a change-up with a hitch in his motion. “I don’t stop,” he said to a reporter, “I stop my stride quick but my arm is still moving.” He paused, “Sure it’s a trick pitch.”

Playing tricky baseball, like talking black, was a choice, not a necessity. It affirmed who you were and whom you disrespected. It did not mean that you could not play or speak like a white man. Rather, unlike Old Pittsburghers, migrants played for other black people. It meant that you were proud to be black.