Tennessee Whiskey and the Whiskey Rebellion

Back in 1981 two songwriters, Dean Dillon and Linda Hargrove, were sitting in the Bluebird Café in Nashville drinking a lot of Tennessee whiskey. Dillon told Hargrove he had an idea for a song about the whiskey and so, at four a.m., they headed off to Hargrove’s place and wrote “Tennessee Whiskey,” a terrific song.

Previously in this series: Rise of the Fern Bar!

David Allan Coe recorded the song that same year and two years later George Jones recorded a more popular version (and my favorite). Then, 32 years later, Chris Stapleton’s version went 14X Platinum, i.e., it sold 14 million copies. Several women have also covered the song, including a notable version by Megan Linsey.

The sweetest version, though, happened in 2017 when a then-unknown guy named Kris Jones was driving his pickup truck down a Texas highway with his cute young daughter, Dayla, heading to Home Depot. Dayla asked her dad to sing “Tennessee Whiskey” and, sitting right there in the Home Depot parking lot, he belted it out. Dayla recorded him with her phone so she could show her friends.

Seventy million YouTube views later, Jones has a Top 40-charting album of his own. Check out his version of “Tennessee Whiskey” on YouTube – if it doesn’t bring a tear to your eye, it’s because you haven’t drunk enough Tennessee whiskey.

Although most of us associate whiskey with Kentucky, where 95% of the world’s bourbon is produced, they’ve been making whiskey in Tennessee since at least 1825. Most Tennessee whiskey distillers, including the two big ones – Jack Daniels and George Dickel – use the so-called Lincoln County Process. Whiskey is made in the usual way, but is then filtered through several yards of maple-wood charcoal, which gives it that remarkable smoothness.

There has long been a debate about whether Tennessee whiskey is or is not “bourbon.” In effect, Tennessee whiskey is bourbon that is then subjected to the “Lincoln County process,” which doesn’t happen with Kentucky bourbon. In that sense, Tennessee whiskey is its own thing and not bourbon (as Jack Daniels insists). On the other hand, since the Lincoln County Process doesn’t add any new flavors to the taste of the spirit, but only mellows it, Tennessee whiskey is virtually identical to bourbon (as George Dickel insists).

Naturally I turned to Chat GPT for the definitive answer, but all the AI bot could tell me is that the question is “controversial” and “will probably never be resolved.”

The chorus of “Tennessee Whiskey” goes like this:

You’re as smooth as Tennessee whiskey

You’re as sweet as strawberry wine

You’re as warm as a glass of brandy

And honey, I stay stoned on your love all the time

That first line is a serious compliment because Tennessee whiskey is as smooth and mellow as whiskey gets. So while the great bulk of the whiskey made in America comes out of Kentucky, Jack Daniels, made in Lynchburg, Tennessee (Lem Motlow, Prop.), is the best-selling whiskey in the world.

The Whiskey Rebellion

These essays originate in Western Pennsylvania – Pittsburgh – and the editor-in-chief of The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails (TOCSC), David Wondrick, is also from Pittsburgh. Wondrick ends the acknowledgements section of TOCSC like this: “To all of yinz, next round’s on me!” So it’s practically obligatory that I speak of the Whiskey Rebellion.

In 1791, right after America won its independence, the new Congress was desperate for revenue to pay off the country’s gigantic war debt. Unfortunately, the very first tax they enacted was also the most controversial tax in US history – the “whiskey tax.”

It was bad enough that the boneheaded Congress had decided to tax a substance that was required for human life and breath. The word “whiskey” derives from the Gaelic “uisge Beatha,” or “usquebaugh,” meaning “water of life,” and as Arnaldus de Villa Nova put it, “It prolongs life, clears away ill-humors, revives the heart, and maintains youth.” (As quoted in TOCSC.)

But it was even worse that the tax was applied unfairly. The whiskey tax fell lightly on the big eastern whiskey makers, but much more heavily on the small farmers of Western Pennsylvania. This was because the more whiskey you produced (usually rye in those days) the lower the per-volume tax.

Could this be because the big producers “owned” the Congress? Could it be because one of the biggest producers of all was a guy named George Washington? The average American distillery in those days produced 650 gallons/year of rye whisky – The Father of His Country produced 11,000 gallons/year.

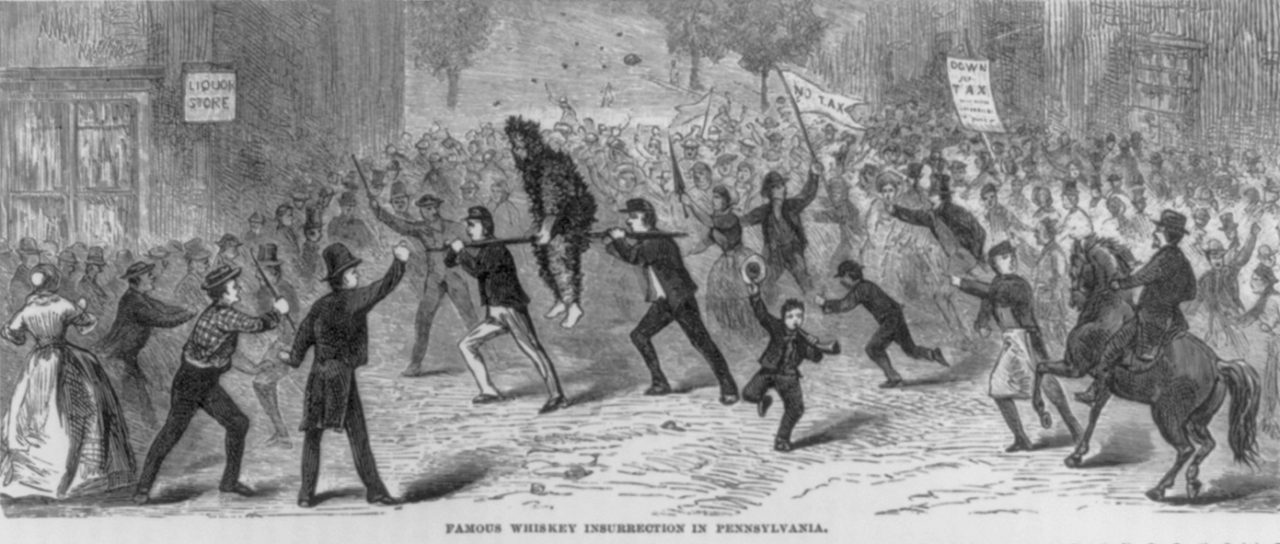

In any event, the farmers refused to pay and when the revenuers came around, the farmers chased them off, sometimes tarring and feathering them for good measure. As tensions mounted, a mob attacked the home of tax collector James Neville and burned it to the ground. (Neville Island in Pittsburgh is named for him.)

Believing that too many people in Pittsburgh were sympathetic to Congress and the hated tax, the rebels assembled 7,000 armed men on Braddock’s Field, just east of the city, and marched on Pittsburgh. The town fathers, being no fools, sued for peace and sent several barrels of whiskey to the rebels as a token of their good faith. That evening, instead of attacking the city, the drunken rebels staggered peacefully though it, waving their new flag – the Whiskey Rebellion Flag.

George Washington, who hadn’t initially favored the whiskey tax and was therefore somewhat sympathetic to the plight of the agitated farmers, tried to negotiate with them but to no avail. Exasperated, Washington did what he did best – he assembled a force of 13,000 heavily armed militiamen and rode at their head to Pittsburgh.

Recognizing that if this fellow could defeat the British, he probably wouldn’t have a lot of trouble with a ragged group of farmer-rebels, the farmer-rebels returned to their homes and Washington returned to Washington and not a shot was fired.

Washington’s actions demonstrated that the new USA was prepared to defend itself even from its own citizens, but it didn’t mean that the whiskey tax was fair or would ever be paid. Not only did the farmers of Western Pennsylvania refuse to pay it, but so did the farmer-distillers of Kentucky.

The armed part of the Whiskey Rebellion may have been suppressed, but the incident led to the formation of the Republican Party, headed by Thomas Jefferson, which among other things opposed the Federalist Party’s tax policies. When Jefferson became President, the Whiskey Tax was repealed (in 1802) and the rebels had won their point.

Next up: The Oxford Companion, Part 12