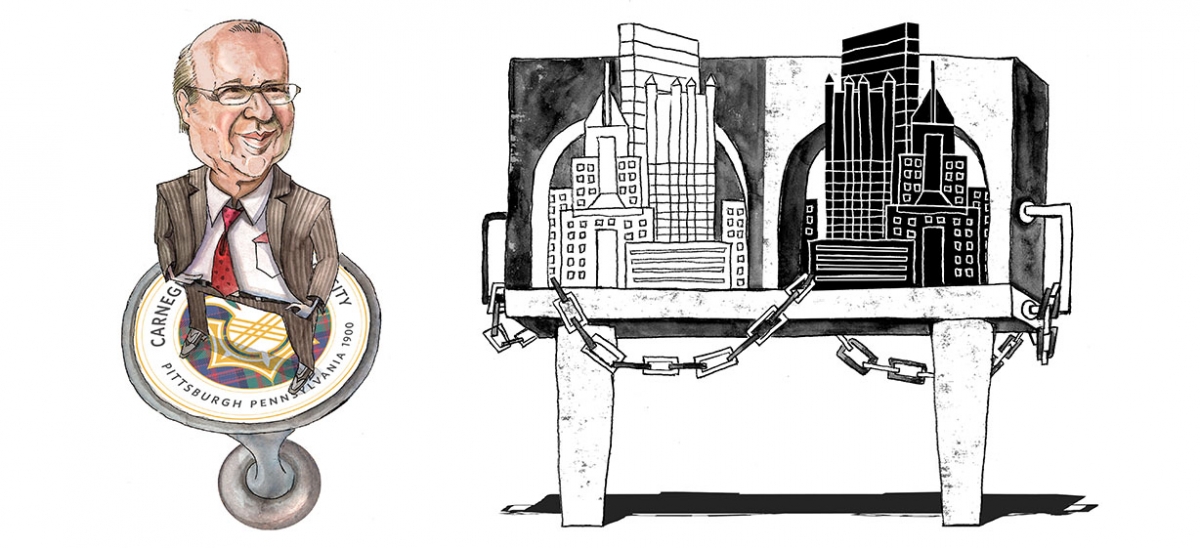

Stocks & Pedestal, Spring 2013

This summer, when Jared Cohon retires from the presidency of Carnegie Mellon University, he will leave enormous shoes to fill.

Since he took the helm in 1997, CMU has seen dramatic growth in the number of overall students—from 7,758 to 12,569—in programs across the globe; the endowment has risen from $592 million to $987 million, despite the dot.com crash and the Great Recession; and sponsored research revenue has more than doubled to $390 million. Nationally, he has chaired the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board and served on the Homeland Security Advisory Council at the request of Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama.

In Pittsburgh, Cohon and Pitt Chancellor Mark Nordenberg created unprecedented cooperation between the two universities, and that has improved Pittsburgh in numerous ways, not the least of which has been the development of new businesses and collaborations. Cohon, a civil engineer, also spearheaded efforts to tackle one of the region’s least sexy but most necessary civic projects—fixing the multibillion-dollar sewage problem. But above all for Pittsburgh, he has significantly increased the stature of one of the region’s greatest world-class assets, Carnegie Mellon.

For all of that, Cohon may be Pittsburgh’s most self-effacing leader. Last year, he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. You wouldn’t know it from talking with him. Count humility among his virtues. When the CMU board asked him to continue for a fourth five-year term, Cohon declined, believing it’s time for new ideas.

Despite the fact that he eschews the spotlight, we’re placing him on the pedestal this issue. The university and the region have been lucky, indeed, to have benefited from Cohon’s efforts these past 16 years. He’ll be teaching at CMU, and with his recent appointment to the Heinz Endowments board, we are glad to know that his leadership will continue.

In the stocks: The racial quality of life gap, a tale of two cities

Pittsburgh has received laurels galore in the past several years as the nation’s most livable city and as one of the best places in America to visit. In a variety of measures, Pittsburgh has come out as one of the nation’s top regions, and leaders from other cities travel here to learn our secret. There is one secret, however, that we should seek to shed.

The most in-depth survey done here in more than 50 years has revealed quality of life differences between blacks and whites so glaring that those of us concerned about the region’s future must take notice.

The Pittsburgh Regional Quality of Life Survey data show that, as of late 2011, the unemployment rate among African Americans was 14.1 percent versus 6.7 for the rest of the region. Nearly 18 percent of blacks often or always have trouble paying for basic necessities—more than twice the hardship rate for other races. Fewer than 15 percent view their schools as very safe, while more than half of other races see their schools as very safe. And more than 1-in-20 African Americans reported being a victim of violent crime—almost three times the rate of other races. Similar data exists in home ownership, health and household income. (You can read more about this at Pittsburghtoday.org).

What is necessary is not just recognition of this gap, but a redoubling of efforts to erase it. It’s not sufficient to say that such problems are worse in other regions. We don’t control what happens in the rest of America—but we are responsible for Pittsburgh. If we seek to continue to build our city—to make it the best in America and beyond—then we must make Pittsburgh the most livable city for people of all races.