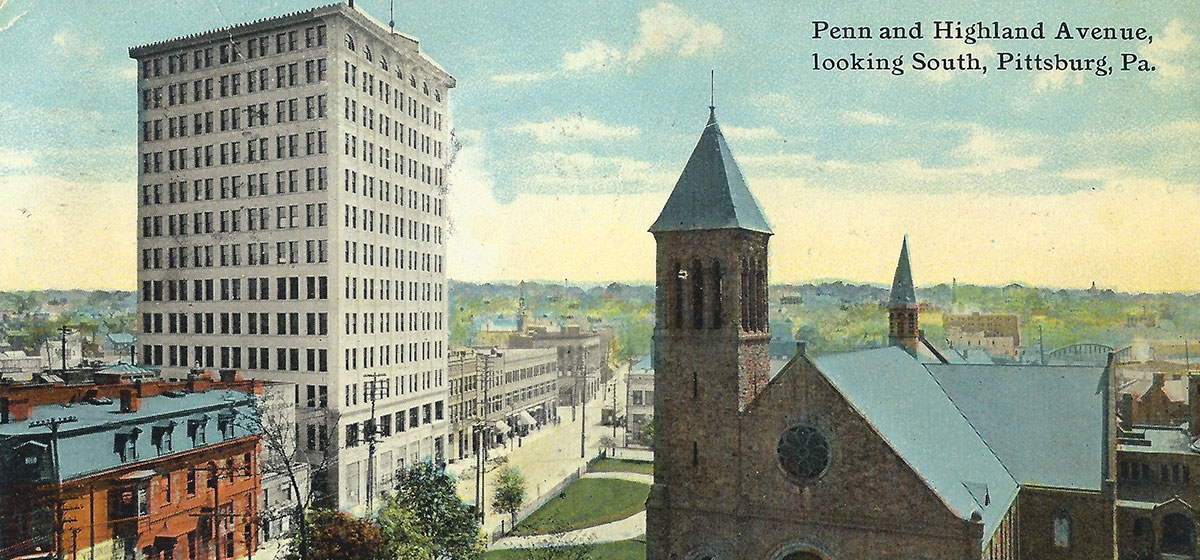

In recent years, it has been difficult to imagine the Highland Building as a “great success as the modern office building,” as proclaimed in a 1910 newspaper ad. The property on South Highland Avenue facing East Liberty Presbyterian Church hasn’t been occupied for a generation. Twenty-five years of neglect have seen a veritable jungle sprouting from its roof; its broken windows poorly boarded up; its cream-colored bricks slathered with graffiti. As one of East Liberty’s tallest buildings, the Highland Building has been a gigantic white elephant.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”62″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

It is, however, a white elephant with a pedigree. The Highland Building was the second-to-last of legendary architect Daniel Hudson Burnham’s 16 Pittsburgh commissions. Burnham is most famous for his pioneering designs for Chicago skyscrapers and his work as consulting architect of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. He also designed many of Pittsburgh’s most famous buildings, including Union Station (now The Pennsylvanian), the Frick Building and the Henry W. Oliver Building.

Burnham began his Pittsburgh work in late 1897, when coke and steel baron Henry Clay Frick suggested to fellow members of the Union Trust Company that the architect might design a building for their headquarters. By this time, Burnham was already what University of Pittsburgh professor Franklin Toker calls “the first starchitect.” Frick had encountered the architect’s influential work while attending the Columbian Exposition, which was certainly Burnham’s most ambitious and grandest commission. What followed were 14 years of commercial and personal commissions from Frick and his cohorts, including Henry Oliver and the board of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

In many ways, Burnham was the perfect choice for these Pittsburgh commissions. During his tenure as half of the firm of Burnham & Root, he was known for having a certain panache with clients. He could manage relationships with high-profile—and often capriciously exacting—businessmen such as Joseph Sears, Philip Armour and Marshall Field. He may have owed part of this skill to his father-in-law; he met his wife, Margaret, while on commission to build a home for her father, stockyard magnate John Sherman. These talents served him well when, after the untimely death of his partner John Root in early 1891, Burnham had to carry on the firm alone, and D.H. Burnham & Co. was born.

In addition to his interpersonal finesse, Burnham was ideally suited to designing office buildings. In 1882, Burnham & Root had designed the first 10-story building in Chicago, “probably the first building ever to be called a skyscraper,” according to Burnham biographer Thomas Hines. Also setting him apart was his “feeling for all those elements which tend to lift a structure out of the category of mere profit-yielders, and make it an ornament to a city,” writes North Carolina State University professor of architecture Kristen Schaffer. With advances in structural and safety materials and inventions such as the passenger elevator, Burnham’s office buildings were not only beautiful, but also practical, and reaching closer and closer to the heavens.

The timing of Frick’s overture to Burnham coincided with the rise of the office building as a significant architectural commission. Schaffer writes that architects had previously focused on prominent symbolic structures such as churches and government buildings until the industrial revolution. “Since that time commercial buildings had become increasingly more significant, so that by the end of the nineteenth century, revenue-producing tall office buildings were among the most substantial commissions architects could receive.”

After the successful execution of the Union Trust Company building (now the Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania), and the construction of the majestic Union Station, Frick commissioned a much more ambitious building from Burnham: a structure that went unnamed throughout most of its design, construction and decoration, until it finally was dubbed simply “The Frick Building.”

The Frick Building was Burnham’s ticket to an ever-growing volume of commercial office projects in Pittsburgh. With its ornately decorated lobby, featuring a pair of bronze lions by sculptor A.P. Proctor and the magnificent allegorical stained glass window, “Fortune,” by John LaFarge, it is an exemplar of Burnham’s best office building work. Robert Brueggman, professor emeritus of art history, architecture and urban planning at the University of Illinois at Chicago, calls it “really one of the greatest buildings Burnham did in his career.” The Mt. Lebanon native also notes that stained glass and bronze sculptures are rare in Burnham’s work.

Commissions for more commercial buildings followed, including the Wood Street Building, housing McCreery’s Department Store (now the 300 Sixth Avenue Building), Frick Building Annex (now the Allegheny Building) and First and Third National Bank buildings. The Pittsburg Dispatch credited Frick with the proliferation of available office space.

“When he built the Frick Building on Grant Street, which is considered the finest and is one of the largest office buildings in the world, that project went a long way toward influencing others to provide big office buildings here.”

“These captains of industry wanted good office space; they wanted a coherent, sedate image for what had become a really chaotic cityscape,” Brueggman said. Indeed, Burnham’s string of Pittsburgh commissions—second in number only to those he did in his hometown, Chicago—do lend a sense of cohesiveness to an otherwise motley group of architectural styles downtown.

Burnham also accepted a number of personal commissions from Frick between 1897 and 1910, only one of which was ever completed—a granite monument for his family’s plot at Homewood Cemetery. The other commissions included a residence on land that is now Frick Park, an art gallery addition to Frick’s summer home in Massachusetts, and initial plans for a home and art gallery on the site of what is now the Frick Collection in New York City. Although Burnham could not seem to earn Frick’s confidence with residential designs, the commercial commissions flowed freely.

What led Burnham out of downtown Pittsburgh and into East Liberty seems to have been Frick’s voracious appetite for investment. By the early 1900s, Frick had progressively invested in Pittsburgh real estate, also funding the Union Arcade and William Penn Hotel in addition to the Frick Building. Frick had purchased several lots of under-improved property on South Highland Avenue between Penn and Centre avenues. The Dispatch gushed, “That Mr. Frick, who is Pittsburg’s largest individual property owner, has decided to put up the first really modern office building in East Liberty is a most substantial evidence of his confidence in Pittsburg. The fact that Mr. Frick, one of the country’s most successful men of affairs, should have decided to invest $500,000 in a business building in East Liberty will no doubt convince many timid investors that they have been indulging in a short-sighted view of East Liberty’s future in a business way.”

In fact, the skyscraper boom of the early 1900s delayed construction on the Highland Building, because structural materials were scarce even in the cradle of the steel industry.

“Not a hand is turning on the Frick building in South Highland Avenue because the workmen have erected all the structural frames on hand and must wait until the mills can turn out more,” the Pittsburgh Gazette reported.

The construction endured setback after setback, with a record-breaking blizzard, contractors who seemed to fit into either the “bungling” or “lazy” categories (“Won’t you endeavor to put a little more ginger into your work?” implored one tartly worded letter from Burnham’s project manager), and even two deaths at the work site. As the work progressed, rumors flew in the press that the building was secretly being prepared for a department store rather than an office building, a story Frick promptly denied.

The terra cotta façade of the Highland Building, which remarkably has survived through its many years of neglect, is similar to other buildings Burnham designed in Pittsburgh and elsewhere.

“The Highland Building was part of an effort in 1909 to create a vernacular for office buildings at the time,” Brueggman said. “It was a formula that worked successfully. All of these office buildings were of a very high quality and not very much different from one another in how they were appointed.”

Toker notes that the building’s design copies two of rival Louis Sullivan’s works in Chicago and Buffalo.

Finally, the Highland Building was ready to welcome the public on May 1, 1910. The building’s initial tenants included physicians, dentists, an osteopath, two dressmakers, a milliner, manicurist and a fifth-floor barber shop. In August of that year, the building played host to the “largest electric roof sign ever constructed” when the Allegheny County Light Company erected a 44-foot-high sign atop the structure. When all 2,800 tungsten lamps were lighted on Aug. 30, 1910, the general public was invited to visit the building and tour the company’s new display room.

“The first floor was ablaze with light,” the Dispatch reported. “In front, facing Penn Avenue, there was one of the biggest electric signs in the world. The floor was set with palms, the perfume of flowers permeating everything. On the floor were electric ranges, and on the shelves chafing dishes, tea trayes [sic], services of all kinds for the kitchen and dining room, lamps and lanterns in multi-colored glass, household affairs so many that they cannot be enumerated.”

Alas, the initial enthusiasm for the building seems to have worn off quickly. There is much archival evidence pointing to problems with keeping the Highland Building occupied and its tenants paying rent on time. Problems with the building continued to mount when, in 1914, the building was sold to Josiah V. Thompson, who died deeply in debt shortly after the purchase. Subsequent owners used the building in its capacity as an office establishment until the City of Pittsburgh bought the building in 2004 after it had been vacant some years. In 2011, the Young Preservationists Association named the Highland Building number three on its annual Top Ten list of best preservation opportunities in the Pittsburgh area.

The building stood vacant as a series of six different developers proposed and then withdrew plans to redevelop the building into a hotel, among other ideas. In April of this year, local developer Walnut Capital announced plans to develop the Highland Building and the adjacent Wallace Building into residential and retail units.

Todd Reidbord and Gregg Perelman, principals with Walnut Capital, said their plan is to completely restore Burnham’s original terra cotta façade. When it comes to the interior, however, restoration isn’t quite as practical. “Unfortunately, the inside of the Highland Building was completely trashed,” Reidbord says. The lobby originally featured terrazzo tile floors and Carrara marble-panelled walls. Although the team has uncovered remnants of these decorative elements, they will most likely be used in some of the upper-floor apartments as accents in the bathroom areas. The City’s Urban Redevelopment Authority was able to help the company secure funding to build a garage, so each tenant will have parking access.

“Based on our experience, a lot of the people who will live in the building are people new to Pittsburgh, graduate students,” Reidbord said. “I think it’s really going to change the whole character of that block. It’s been vacant for so long and once that building comes to life, it’s really going to change things.”

Walnut Capital’s project seems to have been able to recapture some of the excitement that surrounded the impending opening of the Highland Building in its heyday. The company already has a waiting list for the building’s apartments, and the April groundbreaking featured many speakers eager to see the project progress.

“The support and community involvement—it’s been incredible,” Perelman said.

Brueggman is also optimistic about the Highland Building and others like it around the country. “If the buildings managed to survive the ’70s and ’80s, they are much more valued,” he says. “Most of these buildings are appreciated in a way they weren’t in prior decades.”

That one of Burnham’s final Pittsburgh commissions is doing so much to revitalize East Liberty and reengage city residents speaks to the architect’s guiding belief in creating his works. “Burnham had faith in the transcendent power of beauty,” Schaffer wrote. “It informed his idealism and belief that his art had potential for human good.”