Suitcase, Unpacked

I knew my son before he was born. “That’s ridiculous,” my mother said. I was seven months pregnant and had just told her that my unborn son had a great sense of humor.

“How in God’s name,” she said, “would you know that?”

I knew because every time I tried to take a nap, he kneed me in the ribs. When I tried to read sad, academic poetry, he cartwheeled into what may or may not have been my gallbladder. And when I felt sorry for myself, he’d make strange gurgling pops. It felt like hiccupping frogs and, on one sonogram, looked a lot like laughing.

“It feels like there’s a circus in there, that’s why,” I told my mother. “I feel like one of those little cars with clowns stuffed inside.”

“I know one thing,” she said. “I’m glad I was never pregnant. Pregnancy makes you crazy.”

My parents adopted me when I was 1 year old. For years, my mother kept the outfit she wore when she came to pick me up at the orphanage — skinny hot-pink capri pants and a matching turtleneck. She thought pregnancy, with its unseemly swelling and stretch marks and cosmic hormonal swings, was something people should keep to themselves.

“I know one thing,” she’d said when I started to show. “I wouldn’t leave the house looking like that. I wouldn’t leave the house for nine months, if I were you.” But holing up for nine months wasn’t an option. I was a professor at a college. My students expected me to show up. Besides, I thought I looked OK as long as I stayed away from polka-dot maternity wear. And I didn’t feel crazy. If I had to pin a word to the feeling I had, it would be peaceful. It was the kind of peace that comes from feeling grounded and connected — to another person who was part of me but not me, a person who was developing his own life.

“Romanticize it all you want, but I’m going to give you some advice,” said one of the deans. He dyed his hair the color of oily asphalt and jogged around campus in red booty shorts. He had a wife and two grown children, and he liked pretty students.

“Keep him in there as long as possible,” he said. “Once that kid pops, your life is over. Nothing will ever be the same again.” When he said it, he looked sad and wistful. I couldn’t tell him that my son had already changed my life, and I was happy. Some women know early on that they want to have children. I wasn’t like that. It’s not that I didn’t want children or a husband. It’s that I couldn’t imagine being so connected to anyone. It didn’t seem possible.

I know a lot of adopted people who blame all their problems on their initial loss.

“It’s a wound that never heals,” my friend Janelle likes to say. “People think we’re fine, we’re OK, but really there’s no coming back.”

I never believed that. But still, the idea of having a physical and emotional connection, a biological link, was foreign to me. It would be years before I’d meet anyone from my biological family. When I was pregnant with my son, I’d never seen anyone who looked like me or shared my DNA.

For my whole life, I’d felt like a stranger in my adopted family. I knew my parents loved me, but there was always the vague sense of something missing, even if it’s just that we looked nothing alike.

I was blond. My parents had dark hair. I was tall. They were short. It doesn’t seem like it should matter much, but somehow, it does.

When I was very young, my mother used to make us matching outfits. They were pretty outfits — black velvet dresses, gold lamé suits, apricot scooter skirts. When we’d go out to the mall, the bank, or the grocery, I knew it meant a lot to her for people to stop and say, “You two look like twins,” or “She has your eyes.”

A nice cardigan-wearing therapist once told me there is a list of classic symptoms — separation anxiety, intimacy issues, fear of abandonment, fear of powerlessness — that are common for adoptees. Some of them seemed familiar.

“It may explain the intensity of your relationship with your mother,” he’d said. “It may explain a lot of things.” I don’t know if it explains the intensity of what I felt for my son, or the feeling that I knew him long before most people would say that was possible. Many non-adopted pregnant women probably feel the same way. But it did explain one thing. I’d spent my life running away from connections. Aside from my parents and my husband, I’d left nearly everyone who’d ever tried to get close to me.

For years, I was a flight attendant. My happiest moments were when the plane lifted off the ground, and I was separated from everything and everyone I knew. I was happiest with my life in a suitcase, with nothing that could make me hold still.

I don’t have friends from kindergarten. I don’t have many friends from college. I don’t call my aunts on their birthdays. I don’t have friendly relationships with my exes. In the family plot at Braddock Cemetery, the space next to my parents belongs to a cousin. There’s no space for me. I didn’t choose this, but if someone had asked me, I would have.

“Adopted people,” the nice therapist said, “are afraid of being invisible, so sometimes they make themselves invisible.”

Once, at a bar, I explained it to my husband this way:

“I never thought anything I ever did could matter much. I barely even exist.”

It was drunken nonsense.

It was one of the truest things I’d ever said.

But now, I didn’t have the luxury, the self-indulgence, to think these things. And besides, those things, if they’d been true once, were no longer true. There was this other person. Call it physical connection, call it heart. I couldn’t escape, and didn’t want to.

“I think he likes his name,” I told my husband.

“How would you know that?” he said.

“He stops kicking when I say it,” I said. “He’ll be trying to kick my ribs out, but if I rub here and say his name, he stops. Try it.”

I took my husband’s hand and put it on my belly. The kicking slowed, then stopped.

“That’s kind of…,” my husband said.

“Amazing,” I said.

“I was going to say gross,” he said.

Maybe pregnancy does make people crazy. If you asked him now, my husband will say he didn’t say it was gross.

“I said, ‘that’s nice,’” he’ll say. “As in, ‘Quit waking me up. I’m trying to get some sleep here.’”

He remembers what I’ve forgotten.

I remember things he didn’t know.

Like this dream, for instance.

It’s months before our son will be born, but there he is, my son. He has his father’s sweet round face and he’s built solid, like a porkchop. But he’s blond like me, and he has my green eyes, which isn’t fair, since his father’s are blue and beautiful. But it’s my son’s hands that I focus on most. Big, long fingered.

Years later, I’ll find my birth family. When we meet, my sister will ask me to hold up my hands. She’ll press her palm to mine, and my brother will fold his hands over ours. Measuring. We know each other by our hands.

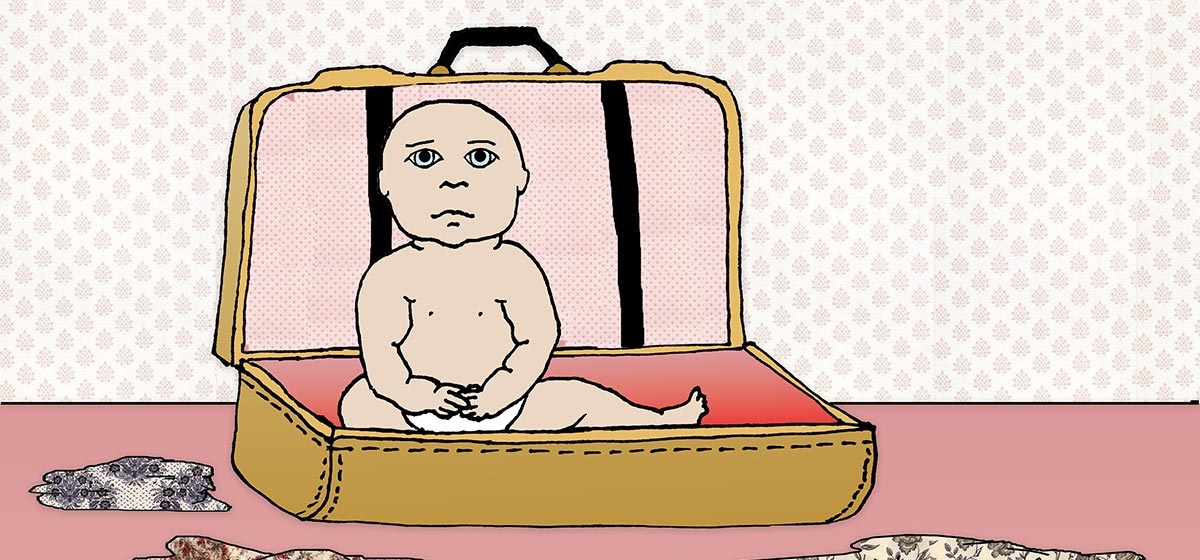

In the dream, my son’s hands are busy. They’re throwing things. Clothes, mostly. He stands inside a suitcase and is tossing everything out. He laughs and throws and makes a huge mess. When he’s done, he looks right at me, like he’s going to say something, but he doesn’t.

It doesn’t matter. I know what he means. I’m not going anywhere.