Room Service in Wonderland

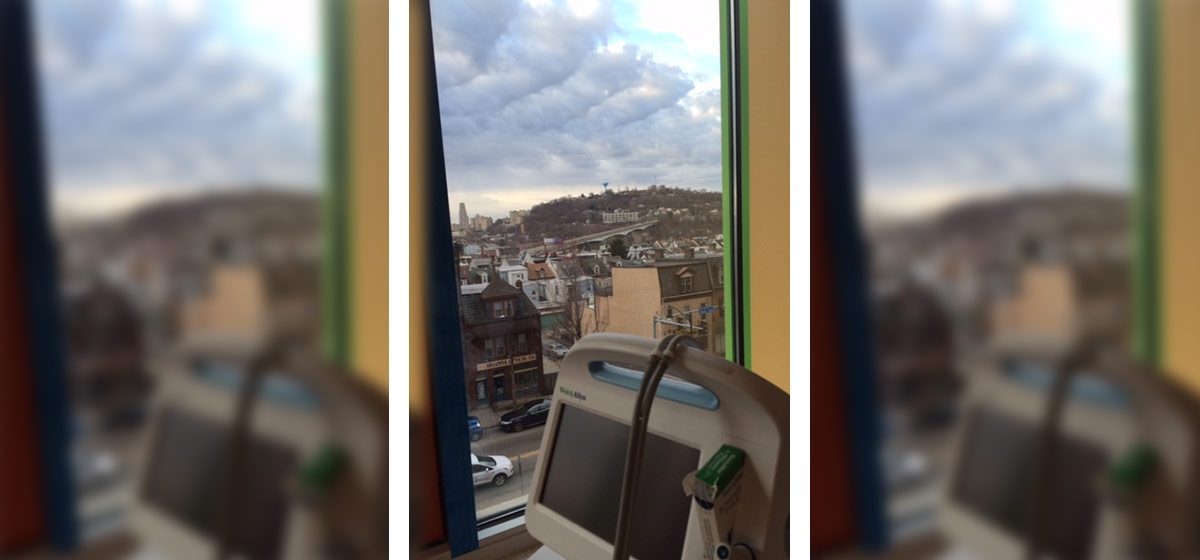

The view from up here is majestic. The smudged, working class neighborhood of my youth has grown up to be a gentrified village whose renovated rooftops peer out of a sanitary blanket of January snow. I can almost hear the bustle of the hipsters and their Uber apps, heading out to work in the city. If the enormous window in my perch on the fourth floor of Children’s Hospital could open, I might maybe hear the vitality below.

The dominant sound in here is beeping. Beeping, beeping. Always beeping, these machines that cycle medicine through my child’s sick body. She doesn’t seem to hear it or be bothered by it. Nor does my pale, skinny girl flinch when yet another IV is inserted into yet another vein. The arm that houses this highway of blood has been warmed by a little plastic “hot pack” to make the insertion of the thinnest of needles more inviting.

The edges of my mouth turn up, but I no longer smile.

My girl and I exchange pleasantries with the women (always women) who will care for us for the next five hours. Our primary nurses are named Jennifer and Jill. My name and my best friend’s name. Funny.

Regardless of our familiarity, I flip on my autopilot. Eyeing the omnipresent computer which greedily withholds information, I repeat for the fourth time in 45 minutes my girl’s date of birth: “ten-eight, two-thousand.” I answer at the front desk, the admissions desk, the first, second and third caretaker “No, we have not been out of the country in the last three weeks.” I sign forms of consent that are inexplicably required, though we were just here two weeks ago. And two weeks before that, and nine other times before that. “Same address. Same insurance.” My quiet girl has only one request: “Please put the IV into my left arm so I can draw with my right.” This too they know by now, her sketchpad and pencils the only belongings she allows into this place.

The mechanical beeping that is as integral to a hospital as syringe receptacles is hard to tune out. What I can silence in my ears are the conversations that swirl around the 800 square-foot pastel room. War stories from strangers mingling together like friends. Little kids, heavy teenagers, red-faced toddlers, parents, guardians exchange information to pass the time. In my melodramatic moments, I imagine this low-level chatter is akin to being stuck in jail: “Whatchya in for?”

Adding to the auditory melee are the dozens of different tunes that bleat out of cell phones resting on portable tables. Sometimes they ding out constantly, reminders of our real lives outside of this place. The Apple cadence interrupts our work here, indifferent to our captivity. Other children will need to be picked up, laundry will be waiting. If we were awake enough as we left at dawn to throw something in the crockpot, we’ll at least come home to dinner. Calendar reminders pop up for explanations to be provided to bosses and excuses provided to teachers.

About mid-way in the infusion process comes the question I dread every time. It’s certainly a valid question. “Is this genetic?” My girl and I give each other the eye and provide the answer that really, is anything but an answer in this context. My daughter is adopted, and I have no knowledge of her genetic history. I don’t want to be unkind to these kind strangers, but the look of embarrassed surprise provides a little glint of satisfaction. I rest my case for looking at the digital paper trail that lives in the mean machine, again refusing to alleviate a shred of worry in this scenario.

Nurses glide in and out of our little corner cubicle. It’s our room with a spectacular view of the unfolding day outside. We never have privacy of course, as women of all colors in scrubs of all patterns move machines and monitors like dance partners in a sterile charade of casualness. They ask us if they can get us anything, but, of course, the one thing we want they cannot give.

Beep. Beep. Beep. Just as a gangly Greyhound with a tag that says “Jennifer” ambles into our cubicle, I receive a text from someone whom I have not heard from in four years. That was before all of this. I feel like Alice, but pushed into a hole by circumstance, certainly not curiosity. Tumbling down through this strange world where hospital comfort dogs (who knew?) appear out of nowhere and characters who missed critical chapters slip into the story. So much like that Wonderland where the girl is asked the same questions over and over again and cannot escape. My phone number is written down and typed in every time, and yet my phone never rings from the doctors. Conflicting directions stream in from different floors, specialists, pharmacists and insurance companies. When I ask for clarification of any medical point, I start back at the beginning of the same circle of non-answers.

The disembodied text glows at me, and my girl is dozing, the medicine taking her energy hostage. Can I meet for a drink tonight? The script starts forming. No, because my girl is recovering, let me get you up to speed…That’s been happening a lot lately. The diagnosis was delivered the same day I started a new job. New colleagues would only know me as the mother with the sick daughter. They would only know my daughter as a kid with a disease. The weird feeling of a “before and after” a life-changing event is common, certainly. What’s disorienting is how to handle it. I want to frame this as non-tragic, because it is. I need to convey that it’s changed me and everyone else in our family irrevocably. The narrative is ours to tell, but how to tell it without putting the recipient of the story immediately in a position of discomfort?

Nothing about this situation is normal, and yet we are two of tens of thousands sitting, waiting for a miracle in a Children’s Hospital in America. Today marks 12 months of battle in a conflict we now know will never end. The army of medical professionals constantly re-upping a tour of duty they signed up for, some fresh from enlisting, others on the front line for decades now know our names. We are the civilians in this conflict, the ones to be saved. To map out their plan of attack against the stupid cells eating the wrong intestinal bacteria, the weapon of choice is a cocktail of immune modulators. They take no prisoners; this medicine is here to kill and heal simultaneously.

The Wi-Fi is pretty strong in our corner of this world, seemingly cognizant that it is our umbilical cord to life outside. When the other constant question is asked rather than pulled out of the smug digital retainer of answers, I stumble. “What medications did you take today?” The names of the legion of drugs waiting for us at home escape me, so I pull up my search history and remember. Mexthotrexate. Pentasa. Flagyl. In an inappropriate fit of giggling, I realize these names could be that of a law firm in some town called Medicinal. These moments light upon me out of nowhere. A form of insanity with jocular voices whispering to provide comic relief for a break in the stress. It’s official. I have become the Mad Hatter.

“If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn’t be. And what it wouldn’t be, it would. You see?”

My girl looks up from her drawing and raises her faint eyebrows. I smile back and register that she’s losing them. Her eyebrows now, in addition to her hair. Soothingly I tell myself that she is so beautiful, this doesn’t impact her looks. She is a porcelain doll, all 74 pounds of her, angular and regal despite this lot. We don’t speak of the hair. The topical medicine that counteracts the side effects of the stupid cell-killing medicine is quietly applied nightly before bed without discussion.

Emergency helicopters chop-chop-chop overhead every now and then, landing with broken cargo on the roof of this place. It would appear to go unnoticed in the beeping bustle of this room. I imagine though, the thoughts of my fellow comrades: “It could be worse. That could be us up there.” In these moments, we share an emotion that doesn’t have a name. Empathy plus fear with numbness and relief. I Google the word for formation of a word. Neologism: the creation of a new or relatively isolated term.

We are almost finished with today’s chapter in the tome of my girl’s treatment. A family limps in the room in salty, tattered shoes. Grandpa or dad shuffles to his girl’s cubicle, behind him, a pinched rumpled twenty-something mom or aunt carrying the man’s oxygen tank in her arms. A sharp wave of anger surges into my throat. I am mad at this person for having the audacity to be ill in the midst of this child’s sickness. The woman has enough to worry about without his troubles on her to do list.

As they settle into their pen, the nurses descend. “Have you been out of the country in the last three weeks?”