Rise of the Fern Bar!

When I first reached legal drinking age most bars were designed to be patronized by men – that is, by people who couldn’t care less what the places looked like. As a result, most bars looked and smelled terrible. (But I quickly got used to it.)

Previously in this series: The Mysteries of Vodka

But along with the pill came the idea that bars should be welcoming to women, and the next thing I knew bars started to look like French whorehouses, complete with (as ChatGPT puts it) “ferns and other greenery and fake Tiffany lamps.”

Most guys would never have gone near the places except that lots of single women were there, and then the first thing I knew, guys were eating spinach salads, drinking cheap Chablis, imbibing sugary drinks and getting a lot more dates than I was getting. Thus arose the “fern bar,” a brief and best-forgotten episode in the long history of booze and sex.

Except that one enterprising entrepreneur decided that money could be made out of the fern bar concept. A guy named Alan Stillman noticed that single women liked fern bars and that single men liked single women. He also noticed that there were hundreds of stewardesses living near the corner of First Avenue and 63rd Street in New York.

So Stillman borrowed $5,000 from his mom and opened a fern bar called Thank God It’s Friday. The place was an immediate success, that is, stewardesses came in in droves, followed by droves of single men. The name of the bar, however, annoyed religious people and so Stillman changed the name to TGI Fridays, claiming that TGI stood for “Thank Goodness It’s Friday.”

As franchises of TGI Fridays began opening all over America and across the world – according to in The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails (TOCSC), there are, today, nearly 1,000 of them in 60 countries – people began to tire of fern bars (and spinach salads). So Stillman and his franchisees “pivoted,” converting TGI Fridays into casual family places focusing on food, rather than booze. As the Tampa Bay Times put it, TGI Fridays and similar chains are now “the culinary equivalent of Wal-Mart.”

Maybe so, but a lot of money was made by guys like Alan Stillman, people who knew that sex and booze mixed together as well as gin and vermouth. And beyond that, whatever we might think of the modern-day TGI Fridays, back in the day they took their booze seriously, “developing a notably rigorous training program” for bartenders (TOCSC). This insistence on making cocktails properly – and often with flair – proved to be a very early precursor of the cocktail revolution of the twenty-first century.

One final note – Stillman also owns the wonderful Smith & Wollensky restaurant in New York. There is no one named Smith or Wollensky – Stillman closed his eyes and picked those names out of a phone book.

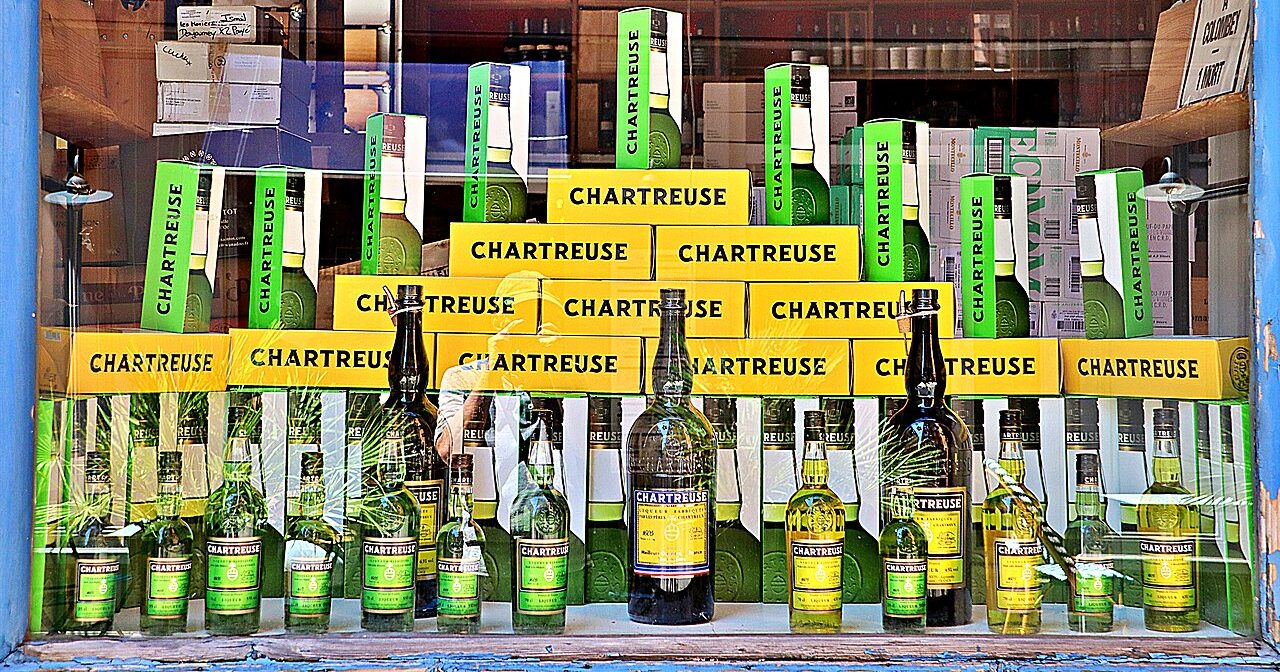

Chartreuse

I’ve already told this story in one of my books, A Few Short Poems, but since that book only sold four copies, all purchased by my Mom, I’ll tell it again.

In the summer of 2021, I found myself in Manchester, Vermont for a few days of meetings. Mount Equinox rises a few miles south of Manchester and there is a private road that winds its way to the top. You have to pay to use the road, I suppose to help defray the costs of its upkeep.

I had a few hours to kill so I headed up the mountain in my car. Naturally, I’d forgotten to check the weather and less than a third of the way up I was encased in dense fog – so much for the wonderful vistas I’d been anticipating.

Near the top of the mountain there is a well-known Carthusian Monastery – the monks live in austere silence and solitude, and some of them haven’t left the monastery since they arrived as young novices three decades earlier. Visitors are not permitted, but at the very top of the mountain there is a visitor center that offers information about the order and the life of the monks.

The Carthusians were established in 1084 when their founder, Bruno of Cologne, built a hermitage in a valley in the Chartreuse Mountains of southeastern France. The order and its monasteries were star-crossed from the beginning. Bruno himself, for example, took a trip to Italy to build a hermitage in Calabria and promptly died.

Then, in 1132, an avalanche destroyed the French hermitage, killing seven monks. Following many other traumas, the current building, a gorgeous medieval marvel, was completed in 1764. Barely a quarter century later, following the French Revolution, the French decided they hated monks and the Carthusians were expelled from their then-new monastery. (They were allowed back in in 1838.)

Although this Motherhouse monastery of the Carthusians, the Grande Chartreuse near Grenoble, is closed to visitors, there is a remarkable-but-hard-to-find 2005 film about the monks called Into Great Silence. Since the Carthusians don’t speak (except briefly on Monday afternoons), Into Great Silence is essentially a two-hour long silent film. Even so, it got rave reviews.

The Carthusian monks have long supported themselves – for 418 years – by making Chartreuse liqueur. (Incidentally, the color “chartreuse” is named for the booze, not the other was around. And the booze is named for the mountain range in France.)

The recipe for Chartreuse is said to require 130 ingredients and only two monks are allowed to know the recipe at any one time. If there is another avalanche that will be the end of Chartreuse.

I read this history in TOCSC and found it so charming that I promptly went out and bought both the green and yellow versions of Chartreuse. They both tasted perfectly awful.

Next up: The Oxford Companion, Part 11