A tree is a house. it’s not just an isolated organism, but also a host to forms of life from mammals to birds to insects to fungi. A tree is one element of a larger ecosystem and simultaneously a microcosm of it. And you can tell a lot about a neighborhood ecosystem based on its trees and who takes up residence.

In Pittsburgh, we’re proud of our differing neighborhoods and the waves of immigrants who have washed over them and then stayed for good, making them better places in the end. The red-bellied woodpecker is one such immigrant, originally abundant in the southeastern United States and expanding northeastward over the last century. In western Pennsylvania, the species indicates the return of wooded hillsides, an avian form of perched homes on the slopes.

In the spring and summer, the estimated 355,000 red-bellied woodpeckers living year-round in Pennsylvania hollowed out their nurseries in most every species of tree. In the fall, they and their offspring prospect for a late harvest of insects and acorns, among other foodstuffs. They abandon their nesting cavities, but not the rest of the tree, which serves as workplace, larder and hangout. Red-bellieds are omnivorous, eating fruits, seeds, dripping sap, and even small frogs and fish from time to time. But we mostly think of them drilling at tree trunks, rattling the hollow deadfalls or, more closely, taking suet from a feeder. They’re a social species in many ways, swooping into a mixed flock of birds at feeders, scattering chickadees and titmice and their far-smaller cousins, the downy woodpeckers.

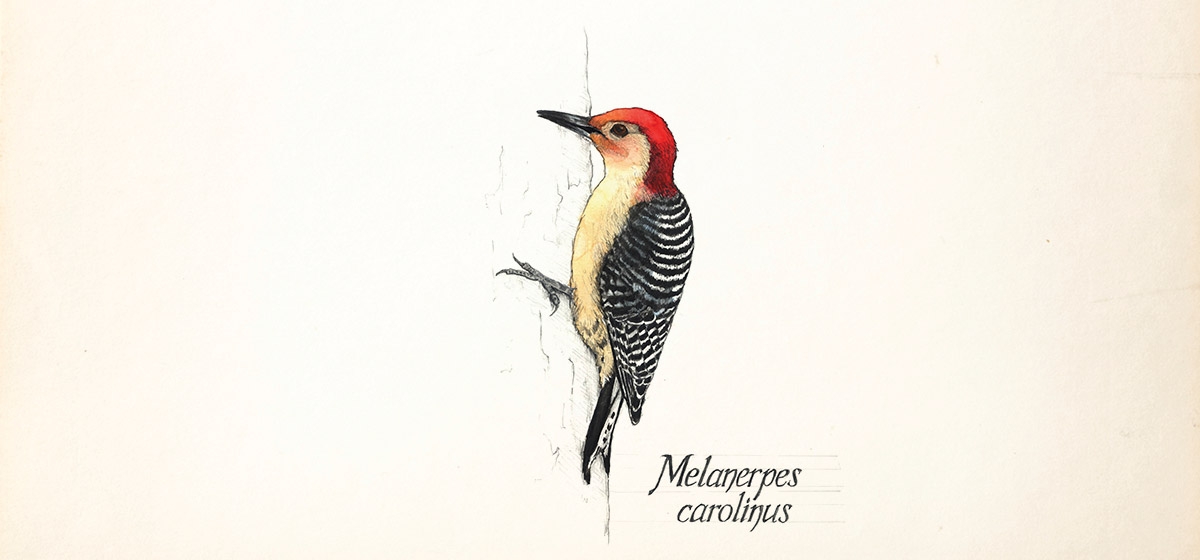

About nine inches high with wingspans closer to 16 inches, red-bellieds are big, with glossy, black bills and flashy stripes of red from nose to nape in the males, a broken line of red and gray on the females. Both genders have wonderfully speckled black and white wings and buffy chests. We see its flashy crimson-striped head and think it misnamed, but next time you see it at a feeder, look for the orange-red wash on its belly, sometimes faint, sometimes deeply stained, and you’ll understand why early ornithologists and hunters named it by what they saw when they held it, limp, in their hands.

Fortunately, like almost all native birds, red-bellieds are protected from hunting today throughout their range. In our area, they make foraging forays in fall and winter, but stay rather close to home. Listening for movement under bark and then using their bills to drill for prey, woodpeckers have the coolest tongues of almost any bird species. Fleshy probes, their tongues are rough, almost barbed, and sticky—great adaptations for yanking surprised insects from crevices and drilled tunnels. Woodpecker tongues are especially long and are connected by bones and muscles to structures deep in the skull that allow the tongue to shoot out far beyond the tip of the bill and then rapidly recoil. Beware, yon creeping critter, the pecker drums for thee.