Pittsburgh’s Greatest Sports Rivalry: Satchel and Josh

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson, who started his professional career with the Kansas City Monarchs, played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers and began the integration of the Major Leagues.

This past December, nearly 75 years later, Major League Baseball decided to elevate Negro League Baseball, founded in 1920, from minor-league to major-league status. The decision formally recognizes that those African Americans, who, unlike Robinson, were denied the opportunity to play in the Major Leagues, nevertheless played at a major-league level in the Negro Leagues.

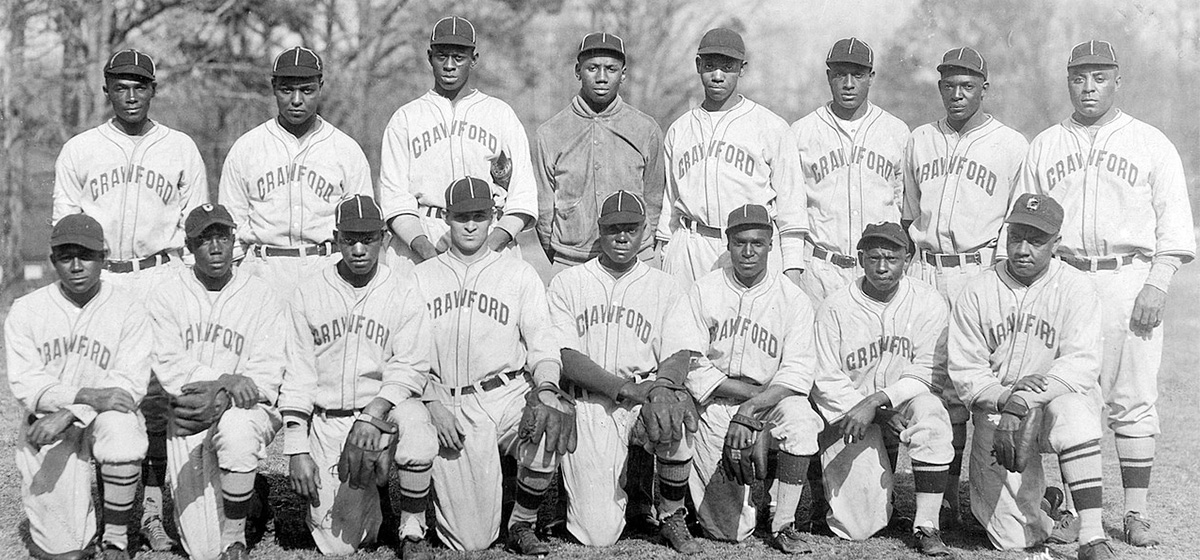

The decision opens the door for the achievements of Negro League players to become a part of Major League history. It means that the records of Negro League legends, like Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard and Smoky Joe Williams will now be included with those of Major League legends like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Walter Johnson. It also means that the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords of the 1930s will now be recognized with the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s as among baseball’s greatest teams and fiercest rivals.

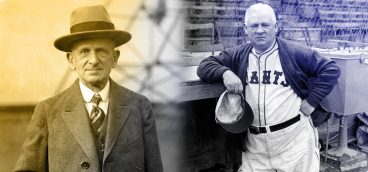

The 1931 Homestead Grays were a baseball powerhouse. They had six future Hall-of-Famers, including Josh Gibson, Smoky Joe Williams, Oscar Charleston, Jud Wilson, Bill Foster, and, for one game, Satchel Paige. The driving force for the Grays, however, was Homestead native and owner Cumberland “Cum” Posey, who would also be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

An outstanding athlete who attended Duquesne, Pitt and Penn State where he excelled at basketball, Posey joined what was then the semi-pro Murdock Grays around 1911. A year later the team became the Homestead Grays. By 1916, he became the Grays’ manager and, by the 1920s, had taken control of the team’s ownership. Over the next decade, he brought Negro League baseball’s greatest players to Pittsburgh, where, without a ballpark of their own, they played their home games at Forbes Field, often outdrawing the Pirates.

Posey’s only problem as the Grays headed into the 1930s was William Augustus “Gus” Greenlee, owner of the Hill’s legendary Crawford Grill and a Pittsburgh numbers kingpin. Wanting his own baseball team, Gus Greenlee used his numbers money to purchase Negro baseball’s greatest stars, and that included players from Posey’s Homestead Grays.

Going into the 1932 season, Greenlee had lured Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Oscar Charleston away from the Homestead Grays. He also brought Negro League stars Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson to Pittsburgh to play for his Crawfords. When Posey blocked his efforts to play home games at Forbes Field, he built Greenlee Field, the first ballpark in America for Negro League baseball.

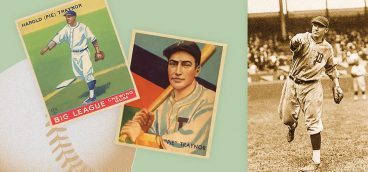

In “Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever,” Satchel Paige declared that for the 1932 season, “I ended up on about the best team ever put together in any country — the best team, white or black. And that was Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords.” He also became part of a pitcher-catcher battery with Josh Gibson that became the stuff of baseball legend. While with the Crawfords in the early 1930s, they became friends despite their differences in age and temperament, but when they left the Crawfords in 1936 to play in the Dominican Republic and eventually faced each other on different Negro League teams when they returned to the States, their confrontations became a part of one of the greatest rivalries in baseball history.

The flamboyant Paige liked to put on a show on the baseball field and didn’t like sharing the spotlight, especially with a younger Josh Gibson. When they were teammates, Paige, despite their friendship, would often claim that the less colorful Gibson, for all his displays of power, wasn’t his equal in talent or as a drawing card.

When they played against each other in the late 1930s and early 1940s, Paige went out of his way to taunt Gibson, often predicting he would strike him out and then doing it. Walking off the mound, he would yell at a frustrated Gibson, “You can’t hit what you can’t see.” Occasionally, Gibson would get the best of Paige, yelling at him, after hitting a Paige fastball out of sight, “If you could cook, I’d marry you.”

Their confrontation reached a climax in the 1942 Negro League World Series between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Homestead Grays. Pitching for the Monarchs, Paige, who, in an earlier game that season, had walked the bases full against the Grays so he could face Gibson and strike him out, was masterful, winning three games in the Monarchs’ four game sweep of the Grays.

At one point, according to the Monarchs’ first baseman, Buck O’Neil, Paige, as Gibson stepped into the batter’s box, told him that he was going to throw him “some fastballs.” After Gibson yelled back, “Show me what you got,” he swung and missed two Paige fastballs and, exasperated, took a third called strike. As Paige walked off the field to the wild cheers of the fans, he told O’Neil, “Nobody hits Satchel’s fastball.”

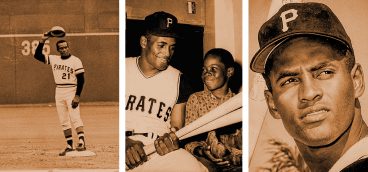

The dominant figures in Negro League baseball, Paige and Gibson believed they had earned the right to be the first players to cross baseball’s color line and were bitter when they learned that Branch Rickey had signed Jackie Robinson. Their fates, after Robinson’s signing, however, would be dramatically different.

Gibson, who struggled with alcohol and drugs during his career, suffered a brain hemorrhage and died at the age 35 on January 20, 1947, just months before Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Wendell Smith, the first African-American to be inducted into the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame, wrote, in an obituary, that had Gibson been given the chance to play Major League Baseball, “he might be living today.”

As for Paige, on July 7, 1948, a little more than a year after Robinson crossed baseball’s color line, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck, who had integrated the American League in 1947 when he signed Negro League star Larry Doby, offered the aging Paige a Major League contract.

Known as the P.T. Barnum of baseball, the flamboyant Veeck was accused of signing the aging Paige as a publicity stunt, but Paige proved that he belonged in the Major Leagues. He pitched brilliantly for the Indians, finished the season with a remarkable 6-1 record, and helped the Indians to their first World Series since 1920. He became the first African American to pitch in the World Series, won by the Indians over the Boston Braves.

When Bill Veeck sold the Indians in 1949, the new owners released Paige, but when Veeck bought the St. Louis Browns in 1951, he again signed Paige, who pitched for the Browns until the franchise moved to Baltimore in 1954. After barnstorming for a few years, he made one last appearance in the Major Leagues, when, at the age of 59, he pitched three scoreless innings for the Kansas City As against the Boston Red Sox.

In 1971, Paige became the first Negro League great inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. His induction, however, had its moment of controversy when Hall of Fame officials announced that Paige’s plaque would hang in a special room honoring the Negro Leagues instead of the Hall of Fame main gallery. When criticized for segregating the Hall of Fame, officials agreed to hang Paige’s plaque with those of other baseball immortals.

The following year, Gibson became the second Negro League great inducted into the Hall of Fame. Denied the opportunity to become the first Negro League players to cross baseball’s color line, Paige and Gibson had finally gained their rightful place among the game’s greatest, though Paige, once again, was a step ahead of his legendary rival.