Pittsburgh’s Famed Stairways to…

“Pittsburgh is undoubtedly the cockeyedest city in the United States. Physically, it is absolutely irrational. It must have been laid out by a mountain goat…And then the steps—oh, Lord, the steps!” –Syndicated Columnist Ernie Pyle, 1937 (as qtd. in “Steps of Pittsburgh”)

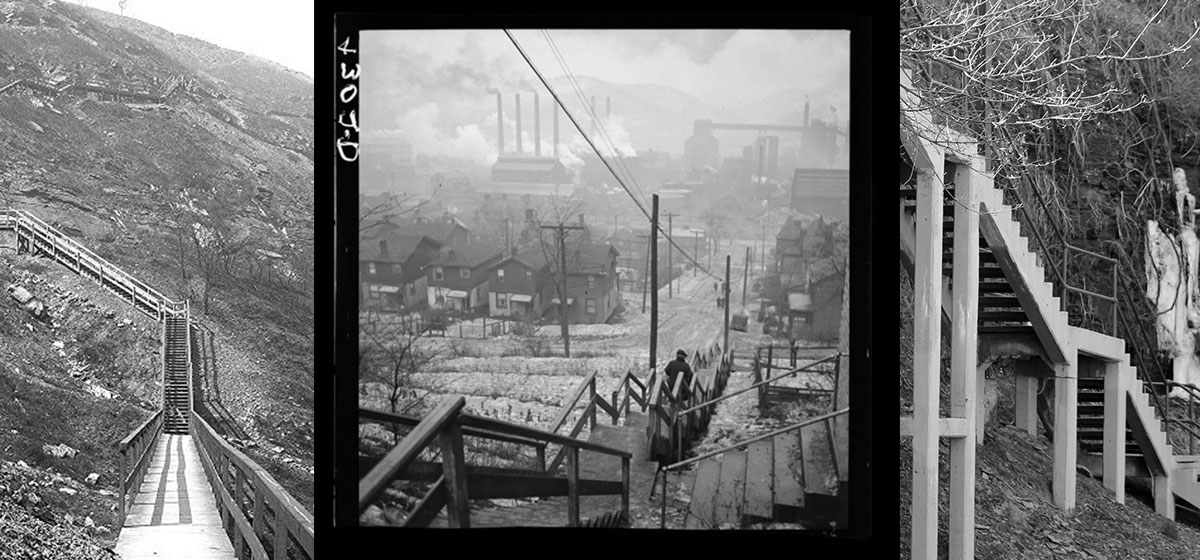

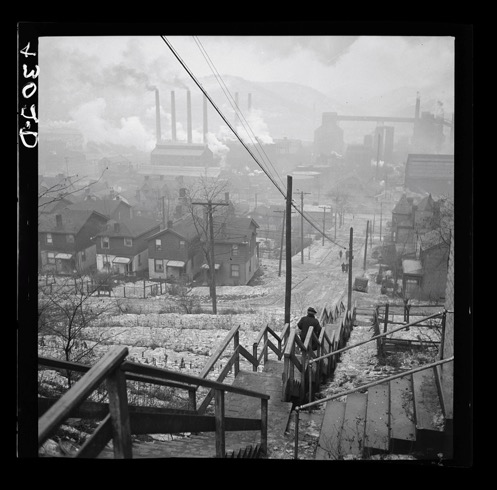

While a first step is a developmental milestone, taking the steps was a childhood rite of passage in my neighborhood. Growing up in Carnegie’s Roslyn Heights, there were three sets of public stairs that could get pedestrians off the hill, the scariest being those that stretched over railroad tracks with big spaces gaping between each wooden slat. I get height fright just thinking about them though they’ve been torn down for years. And while Pittsburgh is celebrated for a steel-making past, winning sports teams and numerous bridges, its abundant and historic public steps have often flown under the radar.

In his 2004 book, “The Steps of Pittsburgh: Portrait of a City,” author Bob Regan makes the case that our “stairways at large” should be another source of pride. With neighborhood enclaves built into the hilly topography where miners and mill-working immigrants settled in the 19th century, public steps became a necessity for travel into the city. Pictures of the Indian Trail steps that once led to the top of Mt. Washington look breathtaking but must’ve been exhausting for workers after a long shift. Today, according to Regan, the city of Pittsburgh has 712 public stairways totaling 44,645 steps. When tallied in full, they span 24,108 vertical feet, or over four miles in height, higher than Mt. Aconcagua in Argentina, the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere.

And while those numbers are impressive, it’s important to consider how steps all over the world have brought communities together and allowed for exercise and commerce, while granting walkers stunning vistas. Locally, they’ve also inspired public art, such as the Oakley Street Steps Mosaic, and Steppin Stanzas, a grassroots poetry project celebrating Pittsburgh public steps and the city’s heritage, diversity, and distinctive geography. Steppin Stanzas launched its project by performing poetry, music, and dance along the South Side Slope Neighborhood Association’s Annual Pittsburgh StepTrek route. Co-Founded by Resident Artists Paola Corso, a poet and literary activist, and Andrew Edwards, a multi-lingual poet, Steppin Stanzas has created original poems inspired by city steps. They were performed with Sahra DeRoy, a belly dance artist, and guitarist Aaron LeFebvre along the South Side Slopes Neighborhood Association’s 16th Annual Pittsburgh StepTrek route.

With the city only budgeting $200,000 a year for upkeep, it’s important to recognize the work being done by volunteers such as the South Side Slopes Neighborhood Organization. Using a Sprout Fund Seed Grant to help launch the project in 2016, Steppin Stanzas events take place on city steps to offer a new way for residents to experience the landscape of their neighborhood and bring art to a venue that few other cities can offer.

It’s in this vein which PQ Poem presents three poems by Paola Corso, also an award-winning author of prose who has found poetic inspiration in not only Pittsburgh’s steps but in others around the world. This feature-length installment of PQ Poem seeks to highlight some of Corso’s work, using photos and poetry’s ability to evoke emotional connections in readers through the seemingly quirky or mundane features of our surroundings that often are taken for granted. It also might give us pause to consider the artistry, engineering and hard work that went into the construction of something that often gets neglected or overlooked. –Fred Shaw, Editor PQ Poem

Journey Down

The Florli Stairs, Lysefjord, Norway

Thousands of wooden steps

run alongside a steel pipe

up to an abandoned power plant

on a mountain so steep they say

when children played outdoors

they were tied to a tree

so they wouldn’t tumble down

thousands of feet into the sea below,

a mountain so steep

that that legend has it

an old man once left

his deathbed in a small village

at the top of the mountain

and walked down to die

so no one would have to carry

his body down the precarious slope.

These steps where I stand,

a forest of ferns tickling

my ankles, my fingertips

running across the pipe’s

oval of shiny rivets. And I see

a bushy tail darting through woods.

What do I feel with my bare skin

that the furry creature cannot?

And the old man who made his final

journey down the mountain to die,

what must he have felt that I cannot?

The pain in his selfless bones,

lifted, freed, ascending

In A Moment

The Spanish Steps, Rome, Italy

Didn’t we stand there once

in the Eternal City, the steps

connecting the piazza at the top

with the one at the base?

A fountain and a wish below.

A church and a prayer above.

Didn’t you gaze into twin bell towers

and pray for good health

after you saw John Keats’ name

on a house beside the steps

where the poet lived, where

he died at the age of 25?

And didn’t I see the fountain

shaped like a half-sunken ship

with water overflowing its bows,

toss my coin, make a wish to be

Audrey Hepburn on Roman Holiday

riding a Vespa with Gregory Peck

to the steps, licking a scoop of gelato?

And was that not our moment

of innocence & experience,

inseparable as they are, as we were

climbing those stairs, climbing

in both directions?

Sweaty Day’s Work

Mission Street Steps, South Side Slopes, Pittsburgh

for Joe Balaban, South Side Slopes Neighborhood Association

My neighbor—he leaves Baltimore flats for Pittsburgh hills and climbs his first set of stairs on Mission Street. Says he doesn’t get all the way up but high enough to be an Alice in Wonderland ducking under trees and finding a row of identical company houses from the old mine.

He’s high alright

like a crow peering out of its nest to see where three rivers meet & bridges line up, where steps

scale the hills

every which way.

In his own backyard’s a pair

near the garden I seen him dig up. His shovel hits brick. He scrapes off the dirt. Each has a company stamp from the factory that used to operate on the slope. He figures bricks are the foundation for the stairs in his backyard until one day he’s tending the garden and the steps collapse.

He put down his hoe and walks over. Instead of a pile bricks, he sees just what the steps are filled with where they buckled under:

a heap of Pabst Blue Ribbon bottles.

Now he’s got this “Geez, oh man, what the…. You gotta be kidding me” look on his face, so I walk over to him and explain something since he’s new in town.

“Joe,” I says to him, “Joe. Let me tell you a little something about Pittsburghers—from Iron City mill Hunks when steel was big to the micro-brewing hipsters: They may damn well run out of bricks on a sweaty day’s job, but they will never, not in your life, ever, run out of beer.”

Steppin

By Paola Corso

Grow up in Pittsburgh—pay no mind to city steps. Leave Pittsburgh—forget they were there. Live in New York—think flat. Not climb. Return to Pittsburgh—hundreds of them!

Steps grounded me. While I was making the adjustment back after 20 years, no way could I picture myself in NYC.

Steps consoled me. Pittsburgh’s got what New York hasn’t got.

And they inspired me. I was a writer in search of a new life, a new muse. I wrote about Pittsburgh rivers in a novel-in-stories and the politics of water for an anthology I co-edited. I wrote about Pittsburgh air and industrial pollution in my poetry books, “Once I Was Told the Air Was Not for Breathing” and “The Laundress Catches Her Breath.”

Now my stanzas are steppin with Pittsburgh’s “horizontal meets vertical.” Wooden steps. Cement steps. Steps my grandfather, who was a stone mason from Sicily, built with concrete fists.

Metaphorical steps like the crystal ones life ain’t in the Langston Hughes poem “Mother to Son.”

I’m climbing, talking to people, listening to stories, interpreting photos, and writing about steps here and around the world—in Norway, India and Italy, the Ukraine, China, Ecuador, and more.

Now I know one step really does lead to another.