Pitt Study: Soaring Municipal Failures Loom

More than 100 southwestern Pennsylvania municipalities will be in financial distress next year if the economy can’t shake free from the grip of the coronavirus and prevent budget reserves from being drained and tax revenues from drying up, a new study suggests.

Municipal officials, uncertain of the duration of the outbreak and severity of the economic fallout, struggled last month to get a reading of the toll it could bring as businesses closed and people were ordered to stay at home. The study is the first to add some definition to those concerns.

Unless the pandemic-driven economic destruction eases soon, the outlook is grim.

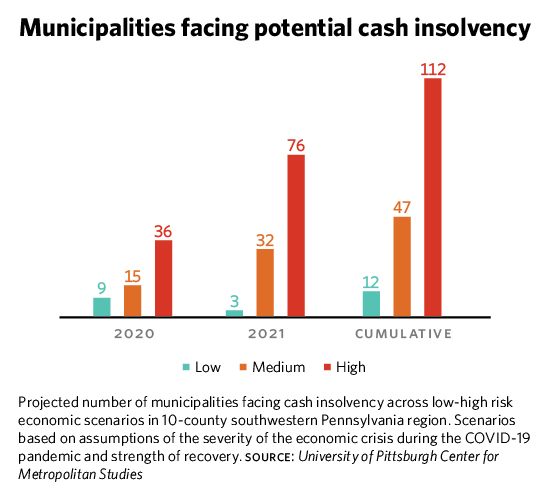

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Metropolitan Studies found that in the worst-case scenario, 112 cities, boroughs and townships would be unable to pay their bills with the money they have on hand if the outbreak and economic downturn continues unabated into next year.

Escalating risk

Their model tested the finances of 525 municipalities in 10 southwestern Pennsylvania counties across three scenarios of economic slowdown. One, assumes a relatively short economic dip, such as what would be expected if the local economy gradually reopens this summer and steadily improves. Another tests municipal financial stamina against a weaker recovery, or one that encounters a setback, such as a resurgence of virus cases that leads to reinstating shutdown and stay-at-home orders.

The harshest scenario is one in which municipalities would struggle through the first half of next year seeing little or no relief from a lagging economy and evaporating revenues.

Most municipalities approached the pandemic with healthy budget reserves that will help them absorb revenue losses this year, the study reports. But prolonged economic pain would consume their reserves next year, if not sooner, and put many on the road to insolvency.

“I’m skeptical that the short-term scenario is likely and fearful that the longer-term scenario is what we’ll see,” said David Miller, a University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs professor and founder of the Congress of Neighboring Municipalities.

If projections for southwestern Pennsylvania are even close, it could mean that financial instability would leave hundreds of municipalities across Pennsylvania eligible for relief under the state’s distressed municipalities act, making it unlikely the recovery program would be able to handle the onslaught.

The study projects the total revenue losses municipalities incur could range from 4 percent to 16 percent, depending on the severity of the economic downturn. Such losses could total $121 million to more than $484 million across the 10 southwestern Pennsylvania counties, the projections suggest.

Revenues from local earned income taxes, business taxes, local service taxes, parking and amusement taxes are the most sensitive to recession. Some municipalities rely more heavily on those taxes, while other municipalities depend more on property tax revenue.

Those who rely more on property taxes, have somewhat of an advantage during the pandemic, at least in the short term. Property tax revenue is usually slower to feel the impact of recession. And most municipalities collected them early in the year, before the pandemic shut down a large swath of the economy. But the study suggests a prolonged recession could erode even that revenue stream.

Unsavory options

Municipalities can’t go out of business. The few options they have to stave off insolvency include raising taxes and cutting services.

Some are in better position to navigate economic turmoil. Others were already burdened by high taxes that earn revenues too low to prevent them from struggling to make ends meet.

There are, for example, vast differences in the value of property across municipalities that determine how much money they can raise from real estate taxes. In McCandless, a 1.23-mill real estate tax brings in $3.2 million. In East Pittsburgh, a 13.45-mill real estate tax is expected to earn the borough only $461,124 this year. Last year, the borough closed its police department.

In Allegheny County alone, 56 boroughs and small cities are among the most financially stressed municipalities in Pennsylvania according to a three-year-old Pennsylvania Economy League study.

Reset button?

The stress on municipalities is particularly acute in southwestern Pennsylvania, which has the most local governments per capita in metropolitan America.

It’s a condition that is blamed for perpetuating stark inequities among communities, slowing economic recovery in those that have long been financially strapped and hampering regional decision making.

Southwestern Pennsylvania has been slow to embrace regional approaches to fixing shared problems. Municipal collaborations have taken root, but remain more the exception than the rule. And merging municipalities in Pennsylvania has proven to be a legal and political challenge so difficult that few attempts have been made to do so.

But the destructive path the coronavirus pandemic is cutting across the region could change that. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” Miller said. “Having so many municipalities facing steep financial losses could well lead to some much-needed innovation in this system.”