On a snowy night, I’m tossing winter batting practice in a gym to nine-year-old boys who play for Steel City Select, an elite Pittsburgh travel baseball club.

We’re getting ready for the 2018 season, another chapter in the history of a game invented by Americans almost two centuries ago, and which has deep roots in Pittsburgh. The kids march in, bats in backpacks, and detach from their parents who head up to a balcony to watch. The boys are happy and yack with each other, and when it’s their turn, jump into the batting cage. It’s a good practice.

What’s happening here is part of a trend upending not just youth baseball in Pittsburgh, but swaths of American life. Like our schools, hospitals and military, youth sports are being packaged, privatized and professionalized. Volunteer-driven, quasi-civic institutions such as Little League and American Legion are losing kids to travel teams like Steel City, squads that mimic the pros funded by upper-class families.

That’s cool if you’re a talented tween with prosperous parents. For this is true: In travel baseball, expert coaching and 50-game seasons make you better; flashy, high-level tournaments are fun; and, if you’re good enough, exposure to college and pro scouts will pay off. For many families, those incentives are too rich to ignore. You also avoid crazy Little League politics: On most travel teams, including Steel City, parents are not allowed to coach.

And this is also true: With so many games to play, kids burn out and hurt their arms. Good players migrate to travel ball, depleting local, volunteer-driven leagues. Baseball without good players to throw strikes and make plays is boring, driving weaker players to quit. Also, travel baseball is expensive.

“Some of the best athletes can’t afford to play, so they play a cheaper sport, like basketball,” says Mike May, who tracks baseball for the Sports and Fitness Industry Association, which represents equipment makers. In addition, says May, with year-round travel teams, “you’re seeing rotator cuff injuries at age 14, because kids with the overhand throwing motion are using too much of the same joint, 11 months a year.”

In Williamsport, Pa., Little League Baseball, Inc. is still the world’s largest youth sports organization. Spokesman Kevin Fountain says it’s sticking to its guns, taking pride in its “more than one million volunteers” who “focus on developing superior citizens rather than superior athletes.” Jeremy Field, who oversees baseball for American Legion, another august American institution, takes a similar tack, emphasizing the “patriotism, sportsmanship and teamwork” kids learn playing for their local post.

Global participation in Little League, which pioneered organized, uniformed play for boys and girls, has declined to 2.4 million from around 3 million around 2000, says Fountain, because of “video games, individual sports, outdoor activities, and more.”

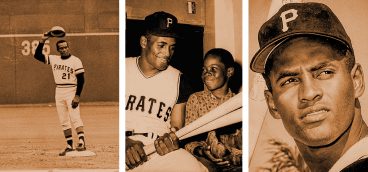

In Pittsburgh, volunteer-run youth baseball has suffered from “losing top talent to travel ball, poor conditions” at some fields, a lack of coaches, and the popularity of football, which starts in July, says Chris Ganter, manager for Youth Baseball Initiatives for the Pirates since 2016.

The biggest risk of this new elitism is that baseball could become like Broadway. “In America, baseball is increasingly a spectator sport instead of a recreational sport,” says John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, and the author of “Baseball in the Garden of Eden,” a history of the game’s early days. Thorn says that travel teams are not necessary: “There are Dominican players who learned without any adult supervision and grew up to become North American folk heroes.”

But when I wanted to get back into the game as a coach, travel baseball is where I found opportunity. I’d played in college, and coached part-time in my 20s. Now 40, I missed it. After applying unsuccessfully for coaching jobs at Shady Side Academy and Ambridge High School, and months of searching for “baseball jobs” on Google, I found an ad recruiting coaches for Diesel Edge Training Academy.

The instructional school belongs to Matt Diesel, a 31-year baseball coach and businessman who also runs Steel City Select, a nonprofit. Diesel is a former outfielder and first baseman for Duquesne University. He started coaching at 19, and founded his own firm when he was 23. Diesel says he’s focused on player development instead of scheduling a maximum number of games, a demand parents place on travel teams. “Does an 11-year-old really need to play a 50-game season?”

Diesel offered me a job coaching the nine-year-olds’ team for Steel City, which has 175 kids, paying between $1,500 and $3,000 per season. They have to try out to make the team, practice year-round, and compete for one of a dozen baseball and softball teams Steel City controls, in tournaments from Pittsburgh to Aberdeen, Md., and Cincinnati.

Diesel says he and his full-time staff of five educate kids and parents about approaching the game in a healthy way. “At the younger levels, the parents are concerned with winning, and at the older levels, they want college scholarships,” he says.

“We’re trying to inspire them to become better people, as well as athletes,” he adds. “And we’d like to prepare them so they know what to expect if they reach the college level.”

Diesel says he’d like to charge less, so that “any kid who has the ability and desire can play with us, no matter how much money his parents make.” Last year, he started a nonprofit, which plans to run clinics in Pittsburgh for low-income kids.

You’d think that baseball pros at higher levels would applaud coaches and parents who take baseball as seriously as Diesel, but many senior baseball officials say they are wary of travel baseball.

“We think baseball is the best game, of course, and we want as many people as possible to play it,” says Rick Riccobono, chief development officer for USA Baseball, the game’s umbrella organization. “But there’s no data showing that if you have some super high-level baseball experience at age eight, you have a better chance of making the major leagues than if you sign up when you’re 14. The longer the air of professionalism can be put off, the better.”

Instead, Riccobono encourages playing more than one sport. He has focused his efforts on helping “the average mom and dad” become better volunteer coaches, including developing an app that has free practice plans. There is a danger in “turning the amateur experience into a business so soon,” he says. “These are supposed to be fun activities.”

But with baseball losing ground, many kids, especially in African-American communities, don’t even have the opportunity to take it too seriously.

In 1989, Major League Baseball started a program called Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities, or RBI, which now has 150,000 kids involved in 200 leagues.

Tony Reagins, a former Angels general manager who oversees RBI and other youth baseball initiatives for MLB, acknowledges that travel baseball is a godsend “and for those who can afford it, Merry Christmas. But for those who can’t afford it, there needs to be an avenue to get quality instruction.”

In a way, Reagins admits, travel baseball offers things that all good young athletes would love to have. What he tries to do is offer the same things for free. For example, MLB runs so-called “development showcases,” a kind of baseball Olympics designed to offer kids a chance to show off skills so they can get recruited by colleges and pro teams.

Reagins praises the Pirates for being “really committed to diversity and growing the RBI program.”

The Pirates’ Ganter says the club helps organize youth teams, host practices and clinics at PNC Park, and assist in Pittsburgh’s RBI program, which includes 850 kids and is overseen by Boys & Girls Clubs of Western Pennsylvania.

Unlike Diesel, Ganter’s job is not to train elite ball players, but simply to get more kids to play. And travel teams aren’t the only force changing youth baseball. For all the talk about burnouts and arm injuries, modern youth baseball has another problem that is forcing organizers to get creative: it’s too boring. As 12-year-old Eli Smith, who lives in Mount Lebanon and prefers basketball, says, “in baseball, you’re standing around too much.”

He’s got a point. Without good coaches and players, baseball is uniquely vulnerable to becoming a sweaty afternoon tea party. Think of the dad you see coaching by himself, standing at home plate, knocking balls to one player at a time, while eight kids stand still; or that practice where the pitcher can’t throw strikes, as minutes turn into hours.

That’s why “game modification” as Riccobono of USA Baseball puts it—or adapting the rules to make it more fast-paced and fun—is now on the table. “We can’t be dependent on 18 players and two coaches,” he says. He helps run the Play Ball program with Major League Baseball, which offers kids variants such as stickball and whiffle ball. “Informal play can be just as impactful as organized play,” says Riccobono. “You can play two-on-two in the backyard.”

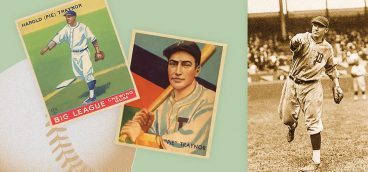

John Thorn, in his book, recounts how baseball grew out of dozens of informal bat and ball games played in early 19th century America with all kinds of rules, including two, three and five bases. In one five-base version, it was only 30 feet from home to first, triggering more action on the subsequent 60-foot basepaths. Players constantly tinkered with rules, looking for balance, challenge and enjoyment.

“The more you inject this spirit of play and innovation into the game, the more the future of baseball is assured,” says Thorn. “The more you make it organized and coach-driven, the more you’re squeezing out the joy.”

Good coaches, from Little League to Legion to travel ball, can make baseball fun and fast-paced, even in a structured environment.

Like 19th century innovators, Reagins, MLB’s youth baseball chief, tinkers with the rules to make baseball more exciting. Once, he helped organize a tournament where, “if you took a strike you were automatically out,” he says. “That made kids swing, and focus on putting the ball in play.”

A nine-inning game usually takes three to four hours. Says Reagins: “We played that one in under two hours.”