On r > g, Part II

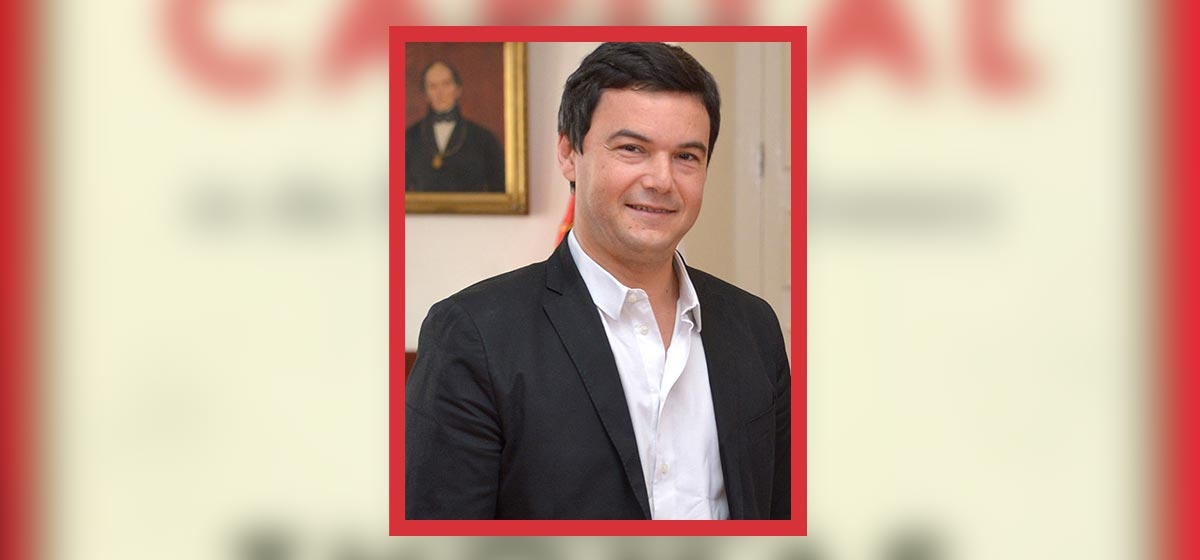

Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” exploded on the scene in mid-2013, but it’s impact faded quickly. I reviewed last week the widely discussed reasons why Piketty’s book fell from grace, but I also proposed a reason of my own: that Piketty is a naïf.

A naïf, for this purpose, is a person who knows his narrow subject matter frontwards and backwards, but who lacks any understanding of how that subject matter plays out in the real world. The cliché of the absent-minded professor is an example. Another famous example involves the finance student who was walking down the sidewalk with a famous University of Chicago professor.

Student: Professor, look! A one hundred dollar bill lying on the sidewalk!

Professor: Impossible, my boy, markets are efficient. If that were really a one hundred dollar bill, someone would already have picked it up and put it in their pocket.

The student picks up the one hundred dollar bill and puts it in his pocket.

Naïve error #1: Equations as truisms

Piketty’s almost charmingly naïve attitude begins with his famous formula, r > g, i.e., the rate of return on capital is greater than the broad growth rate of the economy. Piketty proposes this equation as a “fundamental law” of capitalist economies, and he and his admirers view r > g as one of those deceptively simple equations that is, in fact, ineffably profound, like E = MC2.

But is r > g really that profound? Hardly. Your Humble Blogger can propose a similar “fundamental law” right off the top of his head, intrepid mathematician that he is: 2 > 1.

Brilliant, no? Hold on there, Humble Blogger, you say, that’s not profound, that’s simply a truism! And you would be right: we can’t imagine a world in which 1 > 2. What could such a world possibly look like? Well, it would look like this:

Boss: Curtis, you spend so much time writing your damn blog that I’m cutting your salary in half!

Me: Really? Wow, that’s great! Thanks, boss!

Such scenes don’t happen in the real world, of course, where less is hardly ever greater than more and where Your Humble Blogger would not be enthusiastic about getting his salary cut by half.

What can Piketty actually mean by r > g? First, let’s acknowledge that people with capital will only put that capital at risk if they believe that the return they receive will be commensurate with the risk they took. If that return were no greater than the general growth rate of the economy, no one would invest. And if nobody invested, we would still live in hunter-gatherer societies where the strong prey on the weak, women are procreational slaves, and nobody lives to age forty.

In other words, for human civilization to progress, r has to be, over the long term, greater than g. Piketty’s research, which shows that this is in fact the case comes as a huge revelation to the man, but it’s only a truism.

Naïve error #2: Returns on capital can be achieved without costs

Piketty pays lip service to the issue of investment costs, but he never looks into them. He simply assumes that any idiot can achieve 5% net net net. But as I showed many, many years ago in my infamous “Edith” white paper (technically called “Greycourt White Paper No. 29—Numeracy, Innumeracy and Hard Slogging” (2003), available here), investing capital comes with many, many costs.

Let’s look into this issue by examining one of Piketty’s more amiable literary allusions: Jane Austen. As Piketty points out, Austen was intensely conscious of what it cost to run a household. “[S]he tells us what it cost to eat, to buy furniture and clothing, and to travel about. She knew that to live comfortably… one needed… 500 to 1,000 pounds a year.”

Austen also knew—because she had heard men speak of it—that rents on land (the main source of wealth in the early eighteenth century) were roughly 5% of the land’s value. To dispose of an annual income of £1,000 then, a person would have to own land worth £20,000.

But how exactly is it that land worth £20,000 comes to throw off £1,000 a year? It doesn’t happen magically, as appears to be the case in Austen’s novels and in the mind of Thomas Piketty. Consider the English country house, the sort of place occupied by people with incomes of £1,000/year in Austen’s time. These houses employed 30 to 40 servants, everything from scullery maids, nursemaids, laundry maids, cooks, page boys, footmen, valets, all the way up to the housekeeper and butler at the top of the pyramid.

But houses don’t produce income, they are simply large cost centers. Only land produces income, and that land is managed by a similar army of people, from gamekeepers to blacksmiths to grooms to coachmen to farmers to tenant farmers and, at the top, a steward who oversaw all this activity and who had better be both very good and very honest.

So, sure, there were individuals who reliably earned their £1,000 every year, but it came by dint of hard work and with many possible errors along the way.

Finally, while it’s true that people who had incomes of £1,000/year were comfortable, they were only comfortable because they spent every penny of that income. So instead of the £20,000 compounding at 5% for 200 years, ensuring that the rich would forever dominate everyone else, the £20,000 didn’t compound at all—it just stayed at £20,000 because all the return was spent. And that’s where it would still be today, producing a grand annual income of (in US$) about $1,500/year. Ouch.

Actually, of course, that £20,000 worth of land doesn’t exist at all, because M. Piketty forgot that you don’t get 5% net without incurring a lot of risk. We’ll take a look at that topic next week.

Next up: On r > g, Part III