On Lucretius, Part II: Why His Poem Was so Great

“The greatest poem by the greatest poet.” —Dryden on De Rerum Natura and Lucretius

”Carmina sublimis tunc sunt peritura Lucreti / exitio terras cum dabit una dies.” —Ovid [“The verses of the sublime Lucretius/will perish only when a day will bring the end of the world.”]

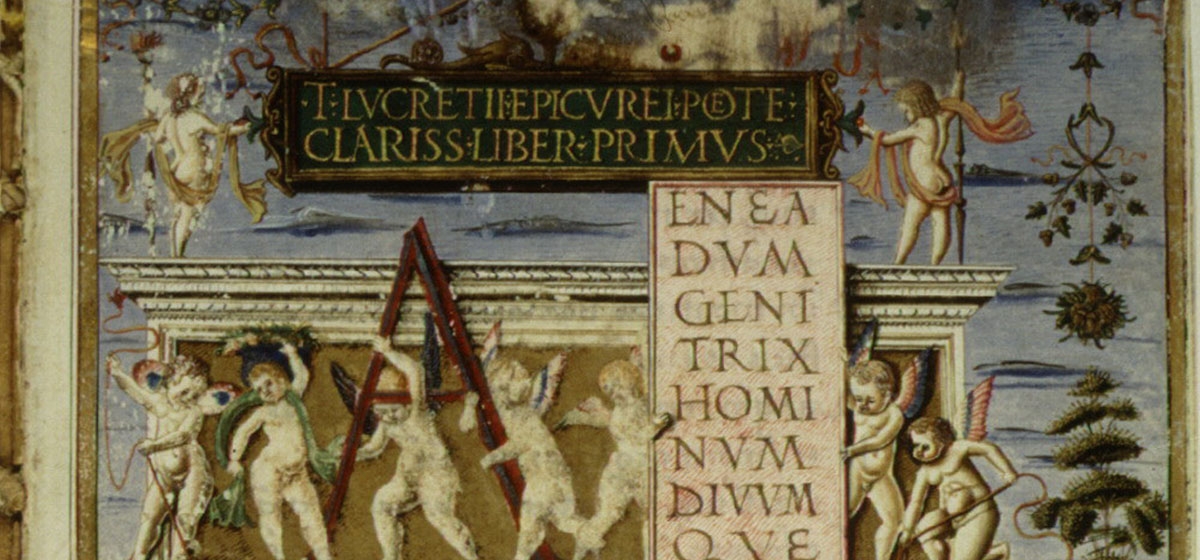

What exactly was it that made De Rerum Natura, or DRN, so remarkable? Well, that’s exactly the problem, because the answer is “almost everything.”

In the first place, DRN is a marvelous poem, one of the greatest ever written, composed in language so shimmering and powerful that, even if its content had been unremarkable, it would, as per Ovid, live as long as people cared about poetry (i.e., until about 1960.)

But the content of DRN is beyond remarkable. In his six books Lucretius discussed, in the most astonishingly modern terms, ideas that, in many cases, no human being had ever had before him and that no human being would have again for at least 1,500 years. Here are a few for-instances:

Lucretius believed that everything in the universe, from himself and his lovers to the sun and the stars, was made of the same stuff—atoms—which are in constant motion and which periodically collide with each other. These collisions, he believed, had momentous consequences for our world. Eventually, J.J. Thomson would prove that Lucretius was right—only 1,947 years later.

Lucretius articulated the uncertainty principle, that is, that the universe isn’t fixed and static, nor guided by divine hands, but that it operates according to scientific principles. Occasionally, however, said Lucretius, the universe “swerves” and therefore can’t be predicted accurately—and also making free will possible. Only 1,977 years later, Walter Heisenberg would (re)discover the uncertainty principle, launching the field of quantum mechanics and winning the Nobel Prize for his efforts.

Lucretius argued, only 1,909 years before the publication of “On the Origin of the Species,” that humans had evolved from apes, which, in turn, had evolved from lower forms of animal life.

Lucretius outlined his views on how human civilization had evolved over time, from hunter-gatherers, to farmers, to urban dwellers, and how we had advanced from working with stone, to copper/bronze, and to iron. 1,784 years later, C.J. Thomsen would articulate the so-called “three-age system,” confirming Lucretius’s ideas.

Along the way, Lucretius described his view of the proper approach to happiness, i.e., the Epicurean belief in ataraxia, a life simply and prudently led with minimal disturbance from anxiety, anger, fear, worry, or other discomfiting emotions, and especially free of the fear of death. Thus, in addition to its penetrating contributions to poetry and science, DRN also importantly influenced modern philosophy. In particular, Santayana grouped Lucretius with Dante and Goethe as the three indispensable “philosophical poets.”

Lucretius speculates about the possibility that different universes may exist, anticipating string theory by only 2,045 years: “Which of these causes operates in this world/It is difficult to say beyond all doubt;/But what can and does happen in the universe/In various worlds created in various ways/That I do teach…”

And note one other quite odd and remarkable aspect of DRN. The work is a philosophical poem, and yet the Latin language had no philosophical vocabulary. Lucretius had to invent words, and create new, theretofore-unknown uses for existing words, simply in order to discuss his ideas.

Thus, the succinct answer to the question, “What made DRN so remarkable?” is this: it was a series of incredible intellectual breakthroughs communicated not in the dry language of philosophy but in the powerful music of poetry. Late medieval scholars were seduced by the language of DRN long before their eyes were opened by its insights.

An interesting parallel is Seneca, not nearly as original a thinker as Lucretius, but whose prose was so powerful that even today he is read and studied far more than many more penetrating philosophers. We read Seneca because we love the majesty of his words, and in the process, almost without realizing what is happening, we come to understand the power of Stoical philosophy. Yet even the greatest prose (Seneca) is to great poetry (Lucretius) what “like” is to “love.”

But before we continue, let’s pause here to notice that Epicurus, Lucretius’s philosophical father, is probably the most misunderstood of all the ancients. If you look up synonyms for “epicure” in your handy thesaurus, you will find words like “glutton” and “sybarite.” While it’s true that Epicurus advocated the pursuit of pleasure, he believed that over-indulgence of any kind was antithetic to true pleasure, which was only to be achieved via simplicity and friendship.

Far from being a connoisseur of fine wine and food, as we think an “epicurean” should be, Epicurus seems to have subsisted mainly on vegetables from his garden and olives from his trees. He famously wrote to a friend, “Send me a little pot of cheese so that I may feast sumptuously.” Properly understood, Epicurianism profoundly influenced Locke, Jefferson and Bentham, among others.

But back to DRN. One way in which the world view of DRN is very much unlike the world we live in is Lucretius’s confidence that art, science and philosophy can easily coexist and that all those fields possessed an essential ethical component. Lucretius proceeded mainly as a scientist in DRN, but with a deep foray into ethical philosophy. And, of course, the entire discussion was conducted in verse.

Today, art and science can’t communicate at all, and if the idea that art should have an ethical component were enforced, we would have no artists. Art and literature, as someone has said, have become “evanescent through a loss of substance.”

In better times, by contrast, artists often anticipated scientific advances. The physicist F. David Peat has pointed out, for example, that Kepler’s ellipses were anticipated by the elliptical structures of the Baroque; that Newton’s experiments with the prism were anticipated by the focus of Dutch painters on the way light enters domestic interiors; that the idea of quanta of light was anticipated by Seurat’s pointillism; that the unity of space and time was anticipated by Cubism.

Those days, we can say with confidence, are long, long gone. But rather than lament what is extinct, let’s turn next week to the interesting question of how someone who lived 2,000 years ago can seem so much like a contemporary of ours.

Next up: On Lucretius, Part III