Myron Cope: The Man Behind the Terrible Towel

For a Steelers fan, watching 60 minutes of football at Acrisure Stadium without a sea of Terrible Towels is hard to imagine. In the mythology surrounding Pittsburgh’s most popular sports franchise, a playoff game against the Baltimore Colts at Three Rivers Stadium on December 27, 1975, marked the first appearance of the “gimmick” that would go on to become a potent symbol for Steelers Nation, with proceeds from the millions sold going on to help some of the region’s most needy citizens. At the intersection of this unlikely pairing stands the uniquely iconic sportswriter turned sportscaster, Myron Cope, a man who was known “to do things his own way.”

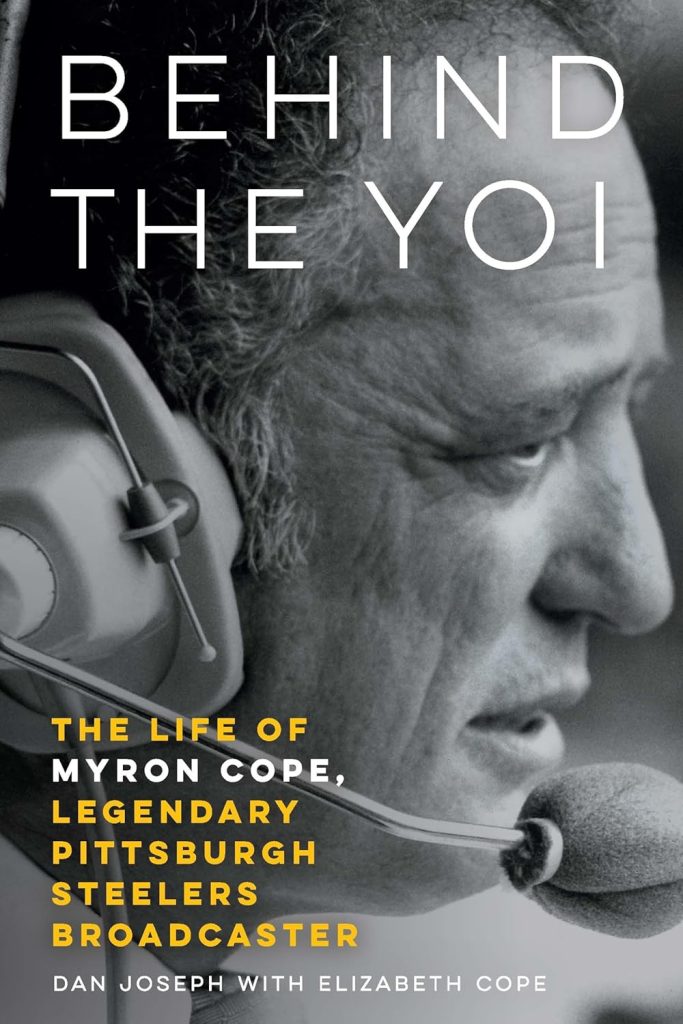

The Life of Legendary Pittsburgh Steelers Broadcaster Myron Cope

by Dan Joseph

and Elizabeth Cope

University of Nebraska Press $34.95

So says the recent book, Behind the Yoi: The Life of Legendary Pittsburgh Steelers Broadcaster Myron Cope a deep dive co-authored by Pittsburgh native and Voice of America newsroom editor Dan Joseph and Cope’s daughter Elizabeth. Its 327 pages reveal a well-crafted, highly readable, warts-and-all portrait of a self-made man whose verbal quirks often overshadowed how he changed the landscape of sports in his beloved hometown. Born Myron Kopelman at Magee-Womens Hospital on January 23, 1929, to Lithuanian-Jewish parents who settled in Squirrel Hill, he quickly grew into a sports fanatic. While boxing and baseball were the headliners back then, the lovable-loser Steelers became his passion, driving him to sneak into their games at Forbes Field.

Though there are funny tales concerning the diminutive Myron being unsuited at playing athletics, Pittsburgh is better off because “his hands would have to work a typewriter instead of a bat and ball.” He’d begin his writing career first at Allderdice High School, and then for the Pitt News, writing sports columns at the University of Pittsburgh that “further showcased his already sharp sense of humor.” An up-and-comer, he found himself writing “short features that showed off his funny bone.” It was editor Joe Shuman at the Post-Gazette who used a phone book to craft Myron’s byline, a name change that became formalized in 1955, though he “greatly disliked the surprise Joe Shuman had sprung.” More importantly, he was kept off the beat at the P-G, later calling the sports department back then “a den of sloths.”

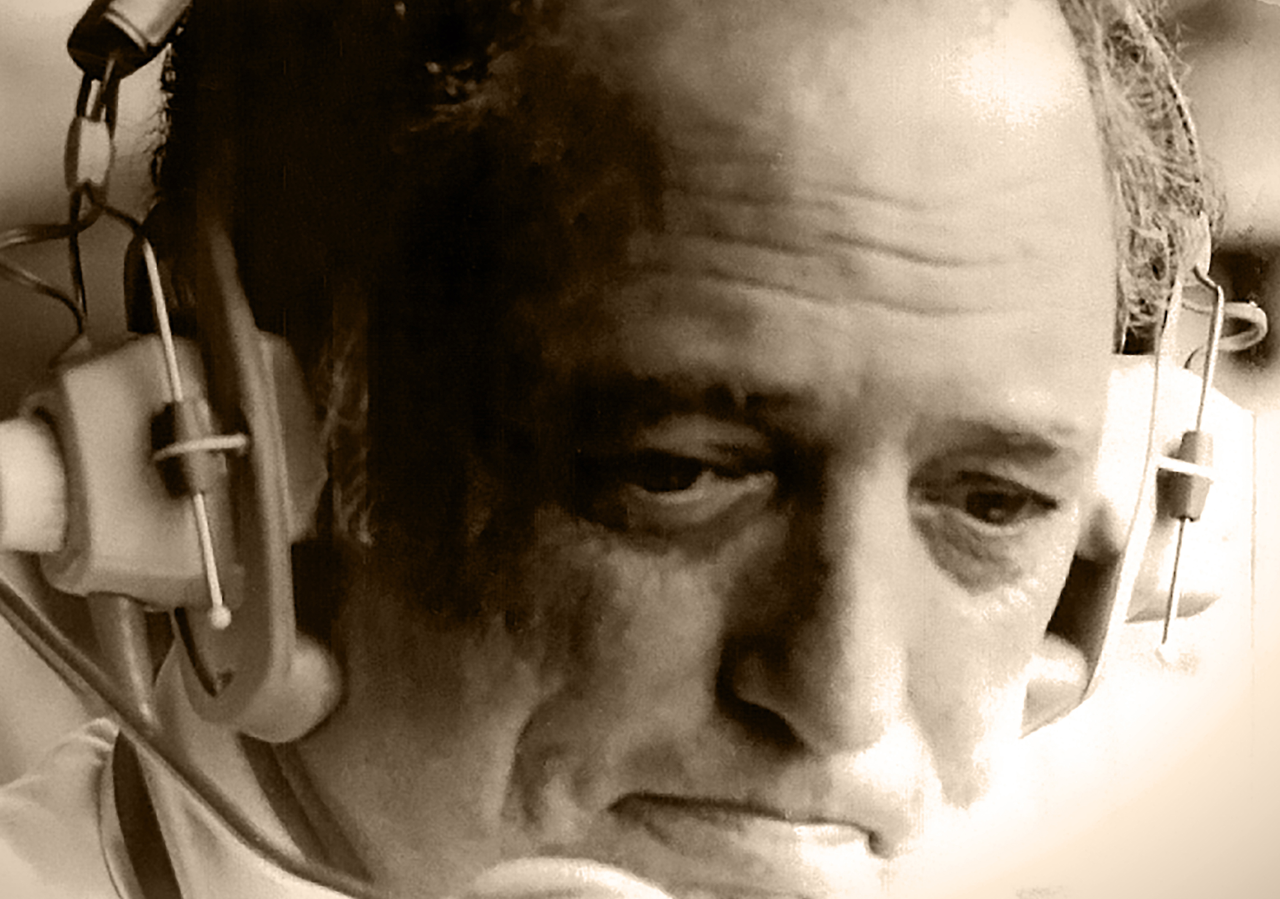

It’s one of many examples that allow Joseph to contextualize Cope’s evolution from young sports fan to a young writer to a pioneer in sports-talk and a member of the Steelers Hall of Fame for his contributions to a team he caught on with as they began their meteoric rise to a dynasty in the 1970s. What’s less remembered about Cope is what came before his regional fame: a freelancer for glossy “slicks” like True and The Saturday Evening Post. As a dedicated member of the backbone of the magazine industry, Cope found writing to be “hard work. … It seemed to me that every sentence had to be crafted, that the writing had to have a rhythm to it, to hold the reader’s attention to the end of the piece. And I could spend an entire morning on the first paragraph.” Yet, to read his pieces for Sports Illustrated on Howard Cosell and “Beano” Cook is to know the man was more than a caricature. He continued to build his talents at WTAE, bringing hometown flavor to the airwaves with a voice self-described as falling “upon the public’s ears like china crashing from shelves in an earthquake.”

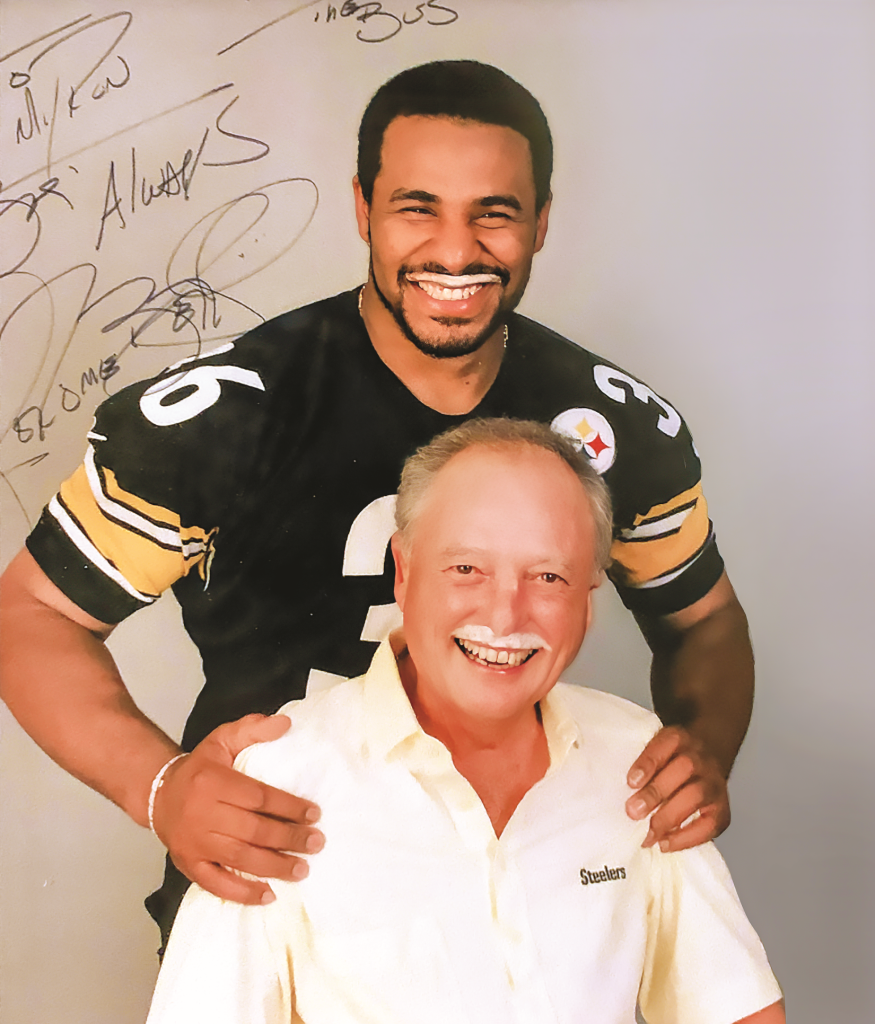

While anecdotes from TV execs, players and other sportswriters abound throughout this compelling life story, it’s the inclusion of his daughter Elizabeth Cope’s perspective on the husband and father that brings him to life in all of Myron’s big-hearted and sometimes flawed glory. Elizabeth Cope is now the vice president of the Family Group at the Merakey Allegheny Valley School, which has been her brother Danny’s home for decades. Though Danny was born with a serious case of autism and has never spoken, Elizabeth once told the New York Times, “It’s almost like the Terrible Towel is Danny’s silent voice.” It’s Myron’s donating all royalties from the Terrible Towel that may remain his most potent legacy, with Myron once telling Elizabeth, “We are responsible for the less fortunate.” Behind the Yoi… stands as testament to Cope’s industriousness and dedication to not just the sporting public, but also to this region’s humanity.